You should never hang onto a conversation, says W. Once it’s finished, pfft , it’s finished. — ‘I forget everything you say as quickly as that’ , W. says, snapping his fingers in the air. I, on the contrary, remember everything, and not only that. — ‘You make things up’, W. says. I wholly invent conversations we are supposed to have had, but in fact we never did have. I’m a fantastist, W. says, a dreamer, but for all that, I’m not without guilt. I’m no holy fool, W. says, no innocent. A fool, yes, but holy — not a bit of it.

I am neither an Eckermann nor a Boswell, W. says. I’m his ape, says W. and (remembering Benjamin’s comment on Max Brod) a question mark in the margin of his life. Well, more like an exclamation mark, says W., or a shit stain.

Of course, W. never mistakes himself for Kafka, as I do. He’s never thought himself anything other than a Max Brod. But the point is — this is W.’s first principle — the other person is always Kafka, which is why you should never write about them or hold on to their conversations, let alone make them up. Yes, the other person is always Kafka, W. says, even me. He knows that, says W., why don’t I?

You have to know you’re not Kafka, says W., that’s the first thing. But you have to know that the person you’re speaking to might be Kafka, that’s the second. This is why conversation, for W., is always a matter for hope. The very ability to speak, to listen and respond, is already something, he says.

Of course, to speak to the other, to respond, is already to betray. Whatever you say is a betrayal, even if at the same time it is suffused with hope. That the other person might be Kafka is a perpetually present possibility , says W. And that you are also the Brod who betrays Kafka is the destruction of this possibility, its disavowal.

In what sense is he Brod? W. wonders. He knows the answer, he says. He never listens enough. He never gives himself over to what is being said. He always comes up short, says W., very short, which is why he always feels troubled when he speaks, yet at the same time always wants to push conversation towards the messianic.

‘Even you’, says W., ‘even you might be Kafka, which would be a great miracle’. Of course, on the other hand, I’ll never be Kafka for myself , but only for him, my conversationalist. The other person is never other for himself , says W. Or only rarely.

For haven’t we along the way met thinkers — real thinkers — who speak without a concern for themselves, without any sense of self-preservation? It’s as though what they say is indifferent to them, we agree. As though they are borne by thought, thought by it, rather than the other way round.

Yes, we have been fortunate to meet real thinkers, W. and I agree. It was our great good fortune. But wasn’t it also our curse? Didn’t we have confirmed for us that of which we would not be capable, that of which we above all would not be capable? It’s important to know your limitations — on that we’re agreed — but to have them reconfirmed so often; to have the sense of them closing around you like a cage?

We’re being suffocated, we agree. How can we breathe? But an encounter with a real thinker is precisely that breath. How is it possible, the sense that, with a thinker, a thought is shared between us? How is it possible that we believe ourselves to participate in thinking? Thought seems to occur between us. It seems to flow there, as though we were gathered around a mountain stream, around thought in its freshness, eternally streaming.

Ah to be near the source, at the beginning point! To have reached the highest, widest plateau with only the flashing stars above us! That’s where these thinkers bring us; that’s the vista their thought provides. Yes, we have seen the heights; thoughts, pure and fresh, have passed beside us.

Were we the condition of thought? We were only its occasion, alas. Someone spoke to us; we looked interested. Someone spoke; we listened. That was it. And thinking welled up around us like a great flood, and there were fishes in that flood, fish-thoughts streaming by us.

That was it, and nothing more. And with what were we left when the flood subsided? Where were we beached but on the valley-bottom of our stupidity, on the parched sands that no thought might cross?

W. sends me a quotation from his notebook:

For the youth of the world is past and the strength of creation already exhausted and the advent of times is very short. Yea, they have passed by, and the pitcher is near to the cistern and the ship to the port and the course of the journey to the city and life to its consummation .

It’s from the Syriac Book of Baruch , a pseudo-epigraphic text from the period of the destruction of the temple, he says. Then he sends me another:

The world endlessly becomes itself, but because this process is endless the world never is the end towards which it moves. Similarly, God endlessly becomes himself by not being what the world has become, but because the world never becomes itself, neither does God become himself .

That’s from Samuelson’s Judaism and the Doctrine of Creation , W. says. It’s meant to be an explanation of Rosenzweig’s idea of creation. W. says I am endlessly failing to become what I am not. A thinker. A good person. A true friend.

Then he sends me a third, from Mascolo’s Le Communisme , the greatest of all, he says, and to which he attaches no commentary:

One writes neither for the true proletarian, occupied elsewhere, and very well occupied, nor for the true bourgeois starved of goods, and who have not the ears. One writes for the disadjusted, neither proletarian nor bourgeois; that is to say, for one’s friends, and less for the friends one has than for the innumerable unknown people who have the same life as us, who roughly and crudely understand the same things, are able to accept or must refuse the same, and who are in the same state of powerlessness and official silence .

Outside, half an inch of rendering now covers the back of the kitchen, I tell W. Today I placed my palm on its grey surface. Wet. Everything’s wet, on both sides of the wall. Apparently there’s a gap between two layers of brick. A gap — that’s where the source of the damp is, I know it, I tell W. That’s where it is: dark, wet matter without shape. Matter without light, as there is in dwarf galaxies stripped of gas.

And the damp’s still spreading. There’s still more of the wall to conquer. ‘It’ll be in your living room soon’, says the damp expert. I nod. Yes, it will be everywhere. The flat will be made of damp, and spores will fill every part of the air. And I will breathe the spores and mould will flower inside me. And I’ll live half in water, like a frog.

It is my own catastrophe, I tell W., it’s very close to me. A secret catastrophe, spreading from the gap between the layers of brick. I take people out there, to the kitchen, and run their hands along the wall. — ‘Feel it’, I say, ‘it’s alive’. They’re always impressed and disgusted.

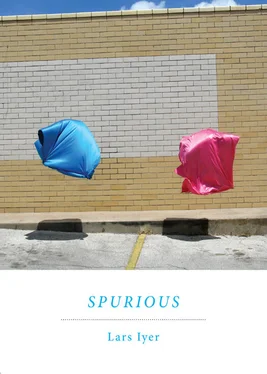

W.’s book has come out, he says. His editor went down to dine with W. and brought him twenty copies of his own book. His editor proofread the manuscript several times and sent it out for proofreading. His book looks great, says W., except for the ancient Greek, which looks terrible. The Hebrew is okay, but the ancient Greek looks as though it were drawn by a child. It’s hilarious.

His book is better than him, W. and I agree. It’s greater. What’s it about? I ask him of a particularly difficult section. He’s got no idea, he says. The book seems to stream splendidly above us both. Neither of us can follow it. Ah, the long example of his dog! It’s even better than the sections on children in his previous book! W. says he’s amazed too. How did he manage it?

Читать дальше