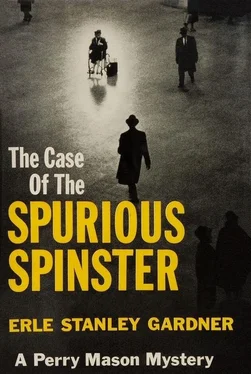

Erle Stanley Gardner

The Case of the Spurious Spinster

Few people realize how important the skilled forensic pathologist is to the individual and to society, how necessary it is that citizens understand the importance of legal medicine.

Even you who are reading this might find yourself accused of a murder you hadn’t committed and in a case where the “victim” actually had died a natural death. You might even be convicted if the “crime” occurred in a jurisdiction where the Coroner’s Office has no skilled pathologist available.

My friend, Richard O. Myers, MD, to whom I am dedicating this book, is a specialist in forensic pathology. He is highly skilled, thoroughly competent, and he can and does, from time to time, tell his intimates about actual cases that illustrate the point I am making.

The average medical doctor is no more competent to perform an autopsy in a puzzling case than an ice skater is qualified to execute a ski jump.

The physician and surgeon specializes in saving the lives of the living. He has to know the physiology and the psychology of his patients. He has to keep abreast of all the new developments in medicine. He knows all about the so-called wonder drugs and, if he is on his toes, he is properly skeptical, so that he keeps a keen eye open for unexpected side effects and individual allergies when he uses some of the new drugs which are being perfected. He has to understand literally thousands of symptoms so that he can evaluate them and make a differential diagnosis. In short, he has his hands so full caring for the living he has little time to study the dead.

The forensic pathologist has to know crime. He has to know all there is to know about dead bodies. He has to know what happens when a body starts to decompose. He has to understand the vagaries of high-speed bullets traveling through human tissue. He has to be able to differentiate between the contact wound of entrance and the somewhat similar-looking blasting wound of exit where a bullet has mushroomed.

The forensic pathologist has to know hundreds of things completely foreign of the general practitioner.

There aren’t too many skilled forensic pathologists in the country today. The reason there are so few is that the public hasn’t been educated to their importance. These men aren’t paid enough, they aren’t given enough authority, and the public doesn’t know enough to insist that a forensic pathologist be available whenever a death occurs under “suspicious circumstances.”

My friend, Dr. Myers, can open his files almost at random and pick out cases where he has been able to keep the guilty from escaping on the one hand, or to keep the innocent from being convicted on the other.

There is, for instance, a case where a very reputable general practitioner in the medical field testified with solemn assurance that certain changes in the internal organs of a body, which hadn’t been discovered until some time after the death, had been due to direct violence. This testimony also resulted in an innocent person being convicted of murder.

But Dr. Myers was able to demonstrate that the death was from natural causes, and that the changes which had taken place were the result of decomposition.

It is a horrible tragedy when an innocent man living an upright life finds himself falsely accused of crime, then finds himself convicted, branded as a felon, sent to prison, and forced to spend the remainder of his life within prison walls.

Throughout the nation today there is a relatively small handful of highly trained men who are dedicating their lives to improving the administration of justice so that murders are not mistakenly classified as natural deaths and so that deaths from natural causes are not mistakenly classified as homicides.

My friend, Dr. Myers, is one of these men.

These men dedicate their lives to discovering the truth. They are far different from the partisan so-called “expert” who gets on the witness stand and glibly rattles off a lot of technical medical terms in order to “win the case” for “our side.”

When Dr. Myers gets on the stand, he wants it definitely understood that there isn’t any our side. He is there to tell the truth as he sees it and let the chips fall where they will.

From time to time I’ve dedicated Perry Mason books to outstanding members of this small select group of forensic pathologists.

The great tragedy, as far as society is concerned, is that this group is so small. It is small, as I said above, because its members are relatively underpaid. Once they have established the proper qualifications, they find more lucrative fields beckoning persuasively. It is far more gainful to become a hospital pathologist than to enter the field of forensic pathology. The only men who remain in this field are those who are actuated by an unselfish, unswerving loyalty to the cause.

We should recognize these men, we should understand the job they are doing, and we should honor them.

It would serve no purpose at this time to set forth the technical qualifications of Dr. Myers, or the vast background of experience which has developed his present skill. His record includes a fellowship in the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, Autopsy Surgeon in the office of the Los Angeles Coroner, Assistant Professor of Legal Medicine at the College of Medical Evangelists, and Associate Clinical Professor of Pathology at the University of Southern California’s School of Medicine, and dozens of other honors that would fill a full page of this book if I had the space to set them forth.

I’m hoping that some day the public will awaken to the importance of having highly competent, specially trained forensic pathologists available in sufficient numbers to do a good job.

Dr. Myers doesn’t care what title is given him or whether the person in charge of investigating deaths is called a coroner, a medical examiner, or a sheriff, just so that person has available a highly trained, duly certified forensic pathologist, and understands enough of the problems of homicide so that the evidence remains undisturbed until the forensic pathologist has a chance to evaluate it.

This is good philosophy. It means a lot more to you and to me and to our loved ones than we seem to realize.

And so I dedicate this book to my friend:

RICHARD O. MYERS, MD.

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER

SUE FISHER — Endicott Campbell’s confidential secretary at Corning Mining, Smelting and Investment Company, she was quick to see the difference between a hundred-dollar bill and a ten-dollar bill but she hadn’t learned that the hand is quicker than the eye

CARLETON CAMPBELL — Endicott Campbell’s young son, he wasn’t big enough to know that if the shoe didn’t fit he was better off not trying to wear it

ELIZABETH DOW — Carlton’s horsy, greedy, self-centered governess, she couldn’t wait for her ship to come in so she tried flying now and paying

AMELIA CORNING — Corning’s arthritic spinster owner, she knew that an apple a day didn’t always keep the doctor away but she also knew that every dog has his day

ENDICOTT CAMPBELL — The overbearing little manager of Amelia Corning’s business, a penny saved was too little earned in his books

PAUL DRAKE — Perry Mason’s tall, dark and handsome detective associate, he ran interference while Perry carried the ball

PERRY MASON — A fast man with a clue, the police could run circles around him but he still managed to keep one jump ahead of them

DELLA STREET — Perry’s secretary and long-time fiancée, she kept the spark alive by keeping just enough irons in the fire

KEN LOWRY — Manager of the Mojave Monarch mine, a loss in Amelia Corning’s books, he insisted a bird in the hand was worth two in the bush until he discovered that if you could sing it didn’t mean you could also fly

Читать дальше