‘This is extremely convenient,’ said the Welshman. He took my mobile phone out of his pocket.

‘Have you had that the whole time?’

‘Yes, I took it from your flat. You are going to telephone someone in Grublock’s organisation who will be able to disable the alarm systems on this building site. I presume you can do that?’

I nodded and he handed me the phone.

I knew this was my last chance. Whether we found Sinner’s body or not, my usefulness to the Welshman would have run out. To my enormous relief, he’d left Tara alive when we politely departed her house in Roachmorton, but I had seen far too much. He would definitely kill me. The fact was, I had nothing to lose. So instead of calling Grublock’s head of security systems I called Stuart.

‘Kevin?’ he said.

‘Hello, is that Teymur?’

‘Are you still in trouble?’

‘Yes, this is Kevin Broom. I’m at the Grublock Homes site on Back Church Lane, and I need you to — hello?’ I’d discreetly pressed the button to end the call. I looked at my phone in fake puzzlement and then dialled again, this time the real number.

‘Teymur here.’

‘Hi, yes, this is Kevin Broom again. We must have got disconnected.’

‘Pardon?’

‘As I was saying, I’m at the Grublock Homes site on Back Church Lane, and I need to gain access. Will you turn off the alarms, please? I’m sorry to call you so late.’

‘What’s this about?’

‘I’ve got a job to do for Horace.’

‘Oh, are you in touch with Mr Grublock? None of us can get hold of him. I’ve been wondering about sending somebody up to check in person, but after what happened last time I did that. …’

‘No, there’s really no need. I’d just be grateful if you could sort out this alarm.’

‘But you’ll need the keys to get on to the site, anyway.’

‘We’ve got them.’

‘You’ve got them? From where?’

‘I’m in a bit of a hurry, Teymur.’

‘Right, sorry. Just give me five minutes and it’ll be done.’

I relayed this to the Welshman. We waited fifteen minutes, to be sure, then we got out of the car and the Welshman picked the padlock on the gate to the site.

Inside, we saw that they were only just beginning to lay the foundations after clearing away the remains of whatever building had stood here before. ‘We’ll use that,’ said the Welshman, pointing to a big yellow digger. Its claw looked like a coffin ripped in half. ‘The rubbish will have been compressed over time, so we shouldn’t need to dig down more than ten or fifteen feet.’

‘You’ll need the key to start it.’

‘No, I won’t. Now, the old woman told us they dug the grave in the middle of the far end of the dump. And if she’s right, the gangster wasn’t using this place so often by the time they buried the boxer, so it should be the first skeleton we find, or at least one of the first. When we think we’re getting close, you can go in with a spade.’

‘It’ll take us for ever.’

‘No, it’ll just take us all night. And we’ve got all night. I needn’t tell you that if you try to run I shall bite your head off with the digger. Remember, we’re looking for a foot with four toes.’

So we began. After two hours the Welshman had excavated a crater of almost lunar magnitude, and there was an ammoniac gnawing at our sinuses that told us we’d reached the upper strata of the old rubbish dump. Standing at the edge of the hole, I watched closely for fragments of bone. Another hour later, my ears aching from the thumps and snarls of the digger, I saw one. It turned out to be part of the spongy pelvis of a dog or cat. Not long after that, the bones of a human foot fell from the claws of the machine. I yelled to the Welshman and he got out to look at it. But it was a right foot with five toes: spooky, but not Sinner’s. We seemed as likely, I thought to myself, to find a hoard of gold coins or the lost manuscript of Archimedes’ On Sphere-Making , but we carried on; and then, finally, as midnight was nearing and I was beginning to lose concentration, the digger ripped away a twisted old bicycle and beneath it, cracked and brown but still unmistakeable, was part of a human ribcage. Again I shouted to the Welshman to stop; then, carefully, I scraped away some more rubble with the spade. From what was left of the skeleton, I could see that it was a great deal shorter than my own. That didn’t mean it wasn’t just a woman’s or a child’s, of course; but a few minutes later I found the detached right foot. Four toes, like a cartoon character. Seth Roach.

The Welshman made me sit down on the ground beside the skeleton and and then briskly handcuffed my hands behind my back.

‘I still don’t understand what you’re looking for,’ I said. ‘Is this what Hitler was talking about in the letter?’

‘No.’

‘What, then?’

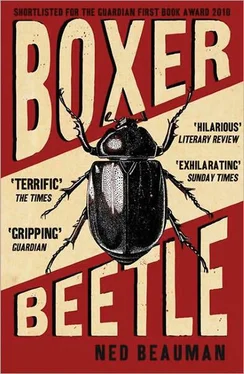

‘The beetle.’

So Grublock had been telling the truth! ‘What beetle?’

‘ Anophthalmus hitleri .’

I had no idea what that was. ‘What makes you think it’s here?’ I said.

‘Be quiet, please.’

‘Look, I know you’re probably going to kill me after this, whether you find it or not.’

‘That’s correct.’

‘I just want to know what all this has been about.’

The Welshman looked at me and sighed, then he said, ‘Two weeks ago, the individual who is now my employer became aware that a private detective was making enquiries about Anophthalmus hitleri . For a long time the consensus has been that there is not a single specimen of the organism, alive or dead, anywhere in the world — but if a serious collector like Horace Grublock believed that somehow, somewhere, some examples might really have been preserved, then that in itself seemed a good enough reason to pursue the possibility. So the aforementioned individual contracted me to find the beetle before Grublock did. Unfortunately, Zroszak had already made excellent progress.’

‘So you killed him and searched his flat.’

‘Yes. It seemed simplest to pick up where he left off, rather than start from the beginning.’

‘But you didn’t find much. Then you saw me go inside. And you thought I might have found something you missed. But actually the letter from Hitler didn’t tell you anything you didn’t already know.’

‘No.’

‘And I wasn’t much help either.’

‘No. Except perhaps at Claramore, and with the spinster.’

‘So why were you looking for Seth Roach’s body?’

‘Zroszak seemed convinced that two of the beetles had been buried along with the boxer. That was in his notes. He didn’t really explain his reasoning. I believe he had access to some notebooks of Philip Erskine’s and some letters of Evelyn Erskine’s which I was not able to find.’

‘And you thought Seth Roach must have died at Claramore.’

‘It seemed likeliest. I was wrong.’

‘Do you really think the beetles will still be here? With him? After all this time?’

‘We shall see,’ said the Welshman. ‘The chemical and microbiological conditions in a place like this are unpredictable. The beetles were bred to be hardy. It’s just possible that they may never have decomposed. They may even have been fossilised in some way.’ Finishing his explanation, he knelt down beside the skeleton. He brushed some filth away from the skull. And then Seth Roach vomited on him.

Black and flickering, the vomit raced up the Welshman’s arm, spread across his chest and swirled up to his chin. He tried to scream and straight away it filled his mouth. Falling on his back, he clawed clumsily at himself, but could barely tear open a gap in the flow, and soon every inch of him was tarred. I heard a sound like thousands of tongues clicking in quiet disapproval; I could see flashes of red and then, worse, flashes of white beneath the boiling slick of black. At first, his whole body thrashed back and forth, but then it was only his hands and feet that shook, and before long even those went limp. Within seconds there was almost nothing left of him but bones, hair, clothes and shoes. Then the beetles came for me.

Читать дальше