‘What do you say, Mr Roach?’ said the reporter.

‘Let’s all go home,’ said Pock.

‘Will no man here assault my testicles?’ shouted the doctor. And that was when Sinner turned and smacked Pock in the face so hard that he tumbled backwards over the ropes and crashed into the gamblers like a bad idea into a hungry nation.

Frink had never seen such a punch, or heard such a cheer. As the boy from Boxing wiped a spray of blood from his glasses and his notebook, the crowd squealed and cackled and howled Sinner’s name like a lover’s, smashing beer bottles and flinging their hats in the air.

‘You ought to be locked up!’ said Mottle to Sinner, hardly able to make himself heard. He turned to Frink. ‘Are you going to let him walk out of here after that?’ Frink shrugged, and handed Sinner his robe as he climbed down from the ring. The doctor was trying to persuade some of the gamblers to help him carry Pock outside.

‘Mr Roach, did he get what was coming to him?’ said the reporter.

‘We all get what’s coming to us, son,’ said Frink.

Dozens of men and women and children got up from their seats as Sinner pushed through towards the corridor that led to the dressing rooms, hoping to shake his hand or kiss his cheek or pat his back or pass him a cigar, but he just looked straight ahead, swearing under his breath. Although he would never have admitted it, even to himself, he liked having fans, and he really liked ignoring his fans, and he’d learnt that ignoring them just made them even more loyal, especially the women. Tonight, most of them were content to pay tribute to Frink instead. The only concession Sinner made was to put his fists up quickly for a photographer.

‘You could have done him afterwards, Seth, if you had to do that,’ muttered Frink.

‘He hit me in the eggs.’

‘Yeah, but you said it didn’t hurt.’

No one remembered how a huge green leather armchair had found its way into the biggest of Premierland’s dressing rooms, but by now it stank of sweat and resin and was vomiting stuffing from its cracks. Sinner sat down and picked up a bottle of gin. ‘You can fuck off, I think, if you’re going to moan like you always do.’

‘You know I am,’ said Frink. He tried to remember a time when the boy wouldn’t have talked to his trainer like that. He could, but only if he remembered so selectively that it became a sort of fantasy. For a while, he’d worried that Sinner’s growing local celebrity might make him harder to control, but in fact Sinner seemed to be almost immune to fame. Not, of course, because of any inner humility — exactly the opposite. The boy had an arrogance so unshakeable that any outside stimulation was basically redundant, a kick up the arse of a speeding train. If Sinner slipped further out of his grasp it wouldn’t be because of fame, but because of a much more banal intoxicant. ‘I need to talk to Pock’s man anyway,’ Frink added as he bent down to tidy away a skipping rope. His forehead and eyelids and the tip of his nose were always very pink, as if he’d once fallen asleep on a stove.

‘Why?’

‘He might try and get you banned.’

‘I won’t get banned.’

‘No, not this time, and not next time, but the time after that you might.’

‘Bye, then.’

‘Don’t finish that too fast.’

Frink went out. Seth sucked on the bottle of gin and then coughed and closed his eyes.

Sixteen years old; seven professional matches (unbeaten); nine toes; four foot, eleven inches tall. These were the numbers that made Seth ‘Sinner’ Roach, all of them pretty low, but what did that matter? Today — 18 August 1934 — he was already the best new boxer in London. To his opponents a fight with Sinner was like an interrogation, every punch a question they could not possibly answer, an accusation they could not possibly deny.

His nickname, like the armchair, was of mysterious origin. ‘Jews don’t have sinners, Seth,’ Rabbi Brasch used to say, ‘we just have idiots.’ When Sinner was sober, there was an intensity to his expression so fixed that, if you gazed at it for too long (which a lot of people did, trying to understand how such a stunted, thuggish physique could be so beautiful), it began to seem not intense but, on the contrary, blank and inert, as when you repeat a harsh word too many times and it loses its meaning; and this changeless quality seemed to deny even the possibility of sin. But everyone called him Sinner none the less. He had oily black hair and thin eyebrows and long eyelashes and small nipples and slightly protruding ears and still, improbably, a full set of teeth.

There was a quiet knock at the door. ‘Fuck off,’ said Sinner. But the door opened, and into the dressing room stepped a tall blond man in a black overcoat. ‘Mr Roach,’ he said, extending a hand. He wore calfskin gloves with pearl buttons and had a neat moustache that did not make up for a weak chin. He carried himself as if he thought he might at any moment have to dive out of the way of a galloping horse.

‘My name is Philip Erskine,’ he said.

‘Enchanted,’ replied Sinner, without moving.

‘I very much enjoyed your performance tonight.’

‘Brought me some flowers, have you?’

‘I’m sorry to intrude like this, Mr Roach, but I didn’t know otherwise when I might have a chance to speak to you.’ While Sinner’s accent was east London with just a trace of his parents’ Yiddish, Erskine’s was the poshest Sinner had ever heard, with the exception of Danny Gaster’s manager — supposedly a disinherited aristocrat — and announcers on the wireless. Seeing he wasn’t going to get a handshake, Erskine withdrew his hand in a way that seemed intended to give the impression he had never really wanted one in the first place. ‘I’d like to make you an offer.’

‘Pretty sister you’d like me to meet?’

‘Actually, I—’

‘Oh, no, should have known. I’m looking at a hardened gangster. You want me to throw a fight.’

‘No, it’s—’

‘I get it,’ said Sinner, taking a swig of gin. ‘You’re going to be a heavyweight. Need me to find you a good trainer.’

‘In fact I know nothing about boxing, Mr Roach. I am a scientist.’

‘How fascinating,’ said Sinner.

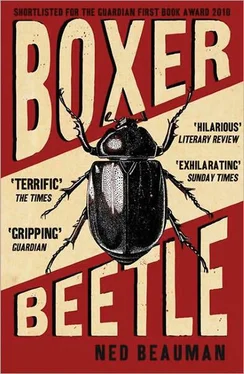

‘May I explain?’ The boy did not immediately respond, so Erskine continued: ‘It’s very kind of you to hear me out. I’ll be extremely brief. For the last four years I’ve been busy with the study of insects. There is very little I don’t know about beetles. But I’ve had enough of beetles now. I want to study human beings. And you are the human being I have most wished to study, ever since I first learnt of your very unusual physiology.’

‘You mean I’m a short-arse?’

‘Yet by all accounts a combatant of remarkable strength and skill. And your father, they say, is equally diminutive, and his father before him?’

‘Yeah.’

‘And only nine toes, if I’m not mistaken?’

‘What’s your “offer”?’

‘May I sit down?’

‘No.’

‘Mr Roach, I would like to give you fifty pounds in exchange for permission to conduct a thorough medical examination and interview every month for a period of five or six months. After that, you would never have to see me again, and you would be kept anonymous in any resultant literature.’

‘Fifty quid to prod me like one of your earwigs?’

‘I can assure you that the examinations would not be unpleasant.’

‘What the fuck is this?’ said Sinner, raising his voice for the first time. ‘You think I need your fucking fifty quid? I’m going to be flyweight champion of the world. I’m not on the fucking dole.’

‘A hundred pounds, then.’

‘Fuck off.’

Читать дальше