At the conclusion of the trial de Wet thanked the President of the High Treason Senate for the correctness of the proceedings, and further for the right of complete freedom to defend himself. He heard the sentence of death with indifference, and with a polite bow left the court, whose tribunal included as lay judges three officers of high military and party rank. [We can imagine that the Gestapo wasn’t taking any chances, and sent over three bigwigs to guarantee and underscore the sentence.]

Everything possible has been done to elucidate the actions and character of the accused. His crime is evident. His character, however, still remains enveloped in mystery. Brought up in two cultures (de Wet attended a French school and speaks French in preference to his own mother-tongue), this descendant of an interesting family — he is related to the Boer General de Wet — is now destined to be a wanderer into nothingness. [And here, giving rise to the frivolous and accusatory adjective “interesting,” appears the Boer grandfather who may not have been all a lie after all. I’ve also found a portrait of him and a book he wrote, but we’d best conclude first with the tale of the Berlin death sentence, the ending of which strays very far from what a journalist’s account of a trial should be, to venture unequivocally onto the terrain of meditation and lament.]

He is intelligent and gifted with several talents, he is fearless and capable of noble feelings, yet he ends his life in a chaos of uncertainty and in the society of dubious men and woman, who all, though patriotic phrases are upon their lips, are themselves without a country and live on foreign money. The ideal of this society is the legendary Colonel Lawrence, but none of them achieves his ideal. Life does not want them and spews them forth [as if they were a costly and superfluous luxury that life expels at once like a breath]: uprooted limbs of a tree that once flourished fruitfully; scattered members of a race whose way of life has become infamous.

Up to this point the speaker has been the journalist from the Vôlkischer Beobachter , who, curiously enough, mentions Lawrence of Arabia as the unattainable ideal of the disastrous De Wet and others of his ilk, though Lawrence himself had died in 1935 in an obscure motorcycle accident or suicide, at the age of 46, my present age.

The translation of the German article complete, De Wet himself begins to speak, as he prepares to embark on his tale:

Thus ran their story of “a wanderer into nothingness.” Though founded on fact, in various respects it was slightly inaccurate, and some of their deductions were wide of the mark. And, obscure though these errors may have been, they still offended the truth; they offended something else, something deeper and more enduring than that — something for which I did not then propose to find a name — could not, perhaps.

The following is my version of the story of myself — and of one other, she who bore me company “on the shores of Avernus” for a little while.…

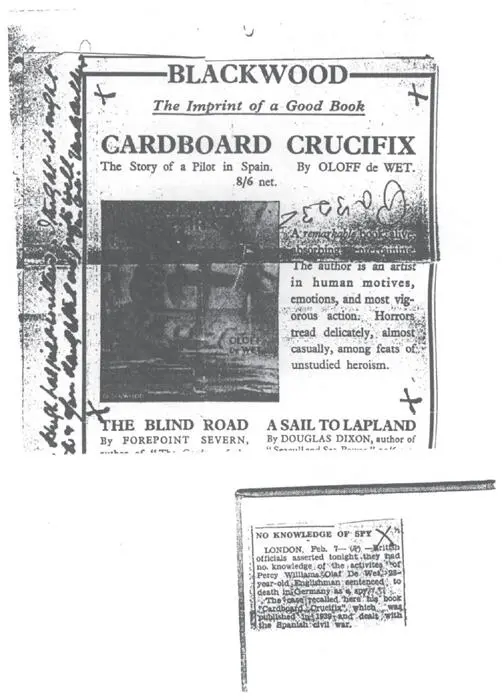

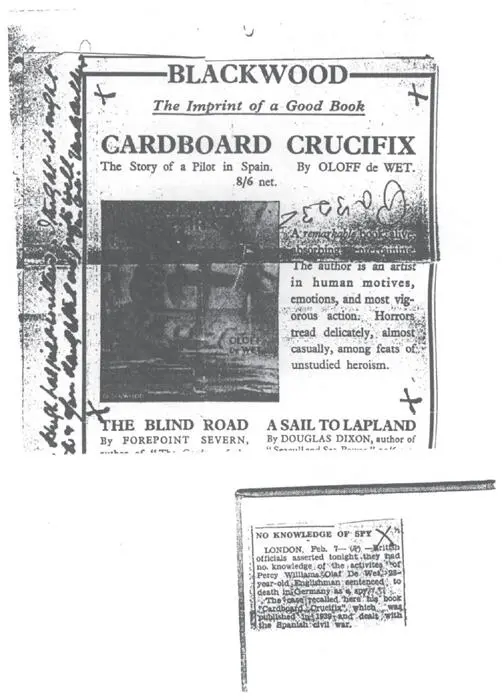

With the passage or loss of time, old books are no longer text and binding alone but also what their former readers have left in them over the years, marks, comments, exclamations, profanities, photographs, dedications or ex libris , a letter, sheet of paper or signature, a waterspot, burn or stain or simply their names, as the books’ owners. Just as the books by Ewart and Graham and Gawsworth spoke of their own short history, one of the two copies of Cardboard Crucifix that were obtained had something between its pages, two or three old newspaper clippings. It must have been Benet’s copy, since I have only photocopies and not the yellow and crumbling newsprint itself. So not only did I conduct myself honorably in the grave matter of the intercepted comb, but I also resisted the understandable temptation to keep what belonged to the second copy which was intended for him, and was not found in my own, more silent copy. I almost always behave well and sometimes I’m even taken advantage of, it can happen. But I’m no saint.

Someone had kept the clippings since 1941—the advertisement even before that — though none of them includes a date or the name of the publication it appeared in. But the size of the largest of them indicates that the De Wet case was in its day and its protagonist’s country as widely known and written about as Wilfrid Ewart’s famous novel had been twenty years earlier. And likewise forgotten shortly thereafter, even more quickly, I imagine, if that’s possible: De Wet was sentenced to death in the middle of a World War, when any news had to be ephemeral, one moment’s news drowned out by the next moment’s, that from one part of the globe by that from another, the same thing happens in our own day, lived as fleetingly as if each second were wartime, I don’t know if this book has a place in its time, it may require patience and slowness; or perhaps it does have a place and belongs to its time alone, for everything in it also passes fleetingly by as it’s told, and if the reader should wonder what on earth is being recounted here or where this text is heading, the only proper answer, I fear, would be that it is simply running its course and heading toward its ending, just like anything else that passes through or happens in the world. But I don’t believe anyone who has reached this point would still ask such a question.

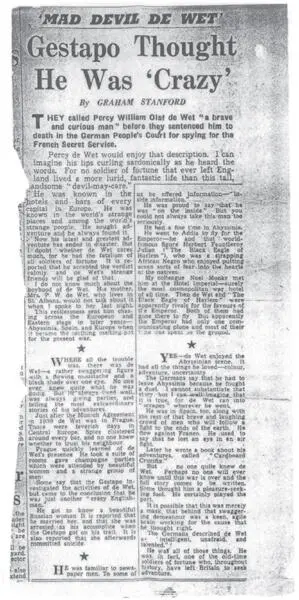

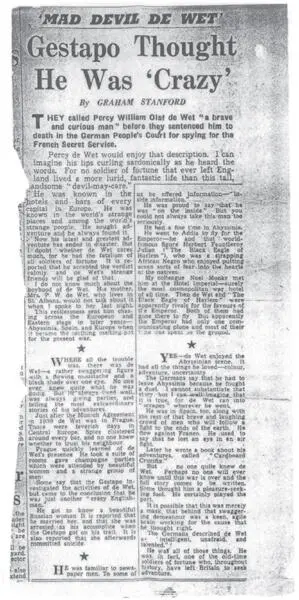

The first and principal clipping was less a news article than a profile signed by one Graham Stanford who, to judge from his comments, had known De Wet personally, though he doesn’t seem any too pained or enraged by his impending appointment with the guillotine. The two headlines are: “MAD DEVIL DE WET” and “Gestapo Thought He Was ‘Crazy’.” And the rest of the evocation or portrait goes on to say:

They called Percy William Olaf de Wet [again the new name, or perhaps it was the name he was using at that time] a brave and curious man before they sentenced him to death in the German People’s Court for spying for the French Secret Service.

Percy de Wet would enjoy that description. I can imagine his lips curling sardonically as he heard the words. For no soldier of fortune that ever left England lived a more lurid, fantastic life than this tall, handsome devil-may-care.

He was known in the hotels and bars of every capital in Europe. He was known in the world’s strange places and among the world’s strange people. He sought adventure and he always found it.

Now his latest and greatest adventure has ended in disaster. But I doubt whether De Wet cares much, for he had the fatalism of all soldiers of fortune. It is reported that he accepted the verdict calmly, and De Wet’s strange friends will be glad of that.

I do not know much about the boyhood of De Wet. His mother, Mrs. P.W. de Wet, who lives in St. Albans, would not talk about it when I spoke to her last night.

This restlessness sent him chasing across the European and Eastern stage in later years — Abyssinia, Spain and Europe when it became the seething melting-pot for the present war.

Where all the trouble was, there was De Wet — a rather swaggering figure with a flowing moustache and a black shade over one eye. No one ever knew quite what he was doing. But he always lived well, was always giving parties, and telling the most extraordinary stories of his adventures.

Just after the Munich Agreement in 1938 De Wet was in Prague. Those were feverish days in Central Europe. Spies clustered around every bar, and no one knew whether to trust his neighbour. [This paragraph seems to imply that perhaps De Wet’s much-rebuked “bouts of drunkenness” merely resulted from the uncompromising fulfilment of certain indispensable prerequisites of his profession as a spy, since his profiler Stanford could have said “around every hotel” or “every café” or “every nightclub” or even “every brothel,” but he says clearly “around every bar.”]

Читать дальше