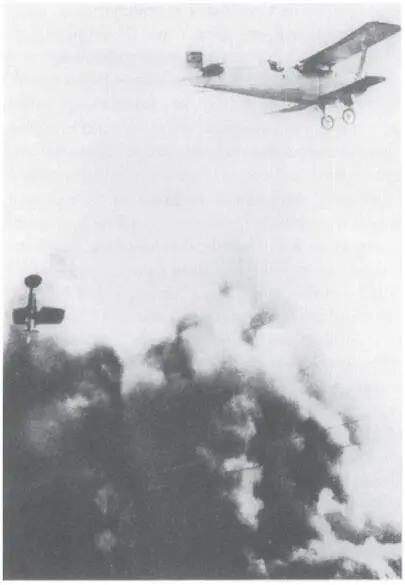

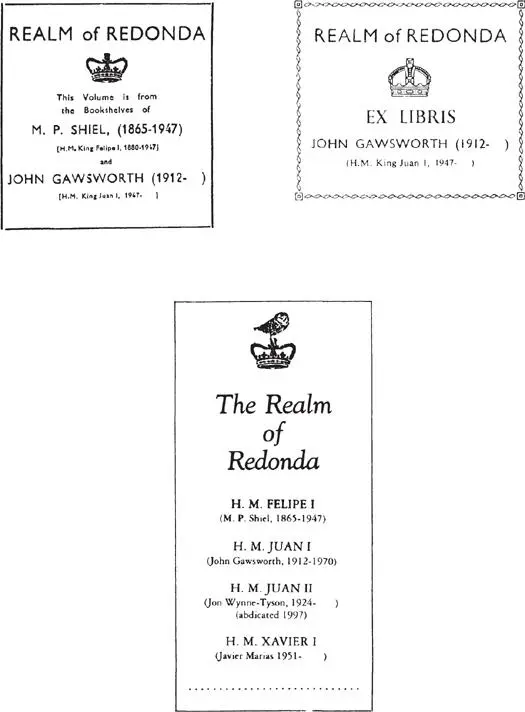

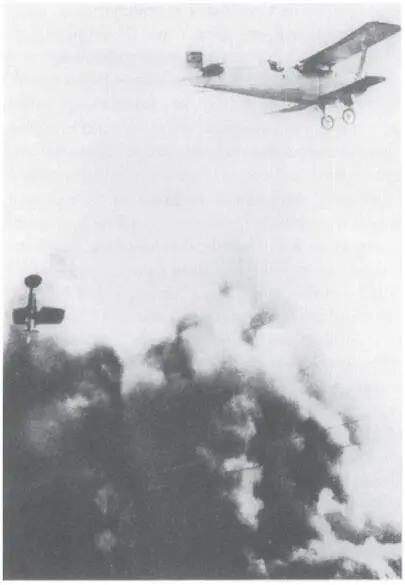

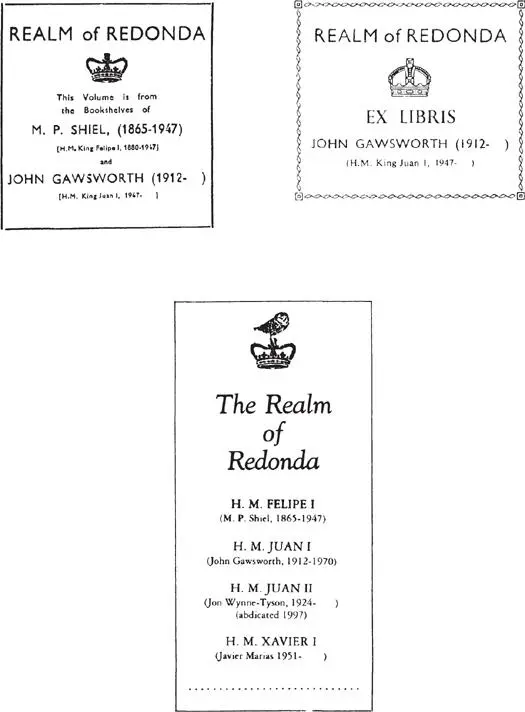

Perhaps in that time, which has so often invaded my own time, I mean, the time assigned to me by other peoples’ standards, fiction is compounded with reality, or with realities that are not only improbable and implausible but incompatible. Perhaps in that time a novel can interfere in real life, and it would not be strange that Sir John Spencer Ewart had aimed his rifle at the tinted lenses of Christaan Rudolf de Wet at Paardeberg or River Vet, or perhaps it was George Steabben who drew a bead on him at Magersfontein or Retief’s Nek, centuries before dying in Mexico of a gunshot to the forehead during the famous shootout between Constantino and Leovigildo at the doors of the Salón Phalerno; it would not be strange that the letter opener with the inscription of the years and the bloody river, “15 Yser 16,” had been carved by Stephen Graham or Wilfrid Ewart in their muddy trenches without truce, or that Hugh Oloff de Wet had sculpted the death mask of the poet monarch John Gawsworth, beggar, or that the spent New Year’s Day or New Year’s Eve bullet didn’t spend itself quickly enough to initiate its downward curve and miss the target, or that the porter Tom and the porter Will of the Taylorian are one and the same traveling back and forth through their eternal territory, “Good luck, professor,” with a festive, obliging hand raised high. It’s possible that in that dimension or time my friend Eric Southworth died seven years ago at the hands of the Galdosistas (truly a sad fate) and my friend Aliocha Coll is still finishing his last glass of wine, and that the patriotic doctor Conan Doyle, the model of all recruits, and Lawrence of Arabia, the unattainable ideal of all adventurers, were the very men who happen to have bestowed the highest praise on the ill-fated talent of the war veteran novelist who didn’t see the bullet his blind eye was to billet in the pandemonium of Mexico City; it may be that the balcony which does not exist on the fifth floor of the Hotel Isabel has always moved through that time, and always, too, the Austrian Ödön von Horváth’s German girlfriend, who saw the same impossible accidental death happen to her father and her lover in the course of a single lifetime, her life, both struck by lightning and the younger man on New Year’s Day; and that this is where Toby Rylands enjoyed his binges with a witty prince of Haiti or Honduras, Antigua or Barbuda or Belize or volcanic Montserrat, or perhaps of Redonda, which is uninhabited; it may be that the entire kingdom, which sometimes appears on maps and sometimes does not, lies and resides within that dimension or time, as befits a place that simultaneously exists and is imaginary, the Realm of Redonda, the Kingdom of Redonda with its intellectual aristocracy of fake Spanish names and its four kings, and it may be that following the abdication of the third one in my favor, since July 6, 1997 I have been the fourth of those kings, King Xavier or still King X as I write this, and also the literary executor and legal heir of my predecessors Shiel and Gawsworth, or Felipe I and Juan I: it’s hard to resist the chance to perpetuate a legend, it would be mean-spirited to refuse to play along; in that nebula must float my alternating memory and non-memory of a scar on a thigh like a smooth, scorched crater that I saw and kissed every day for three distant years, and certainly also the occasional thought or the now almost fictitious memory of the person who bore it (“Oh yes, a young man used to live here with me, he was from Madrid, I wonder what’s become of him, that was so long ago”) and in that penumbra must invisibly smolder the kinship I’ve acquired with the actor Robert Donat through the objects of his that are mine now, the cigarette case in our pockets and the pin in our ties or on my lapel; and maybe De Wet is still piloting his Nieuport through that domain or in that wind, who knows if it isn’t that very airplane which is moving off, high and alive, while the enemy falls into an inferno (but it may be a Polikarpov and not a Nieuport, and then it would not be De Wet who pursued and brought down); and it may be that that adventurer coincided in Spain with another one whose escapades were of longer standing, the Red Dean, the bandit Dean of Canterbury, for whose cause and involuntary trumped-up accompaniment death was on the point of not passing my father by, and of leaving me without existence. Perhaps the unlived and truncated life of my small elder brother Julianin also moves through the other side of time, along with the person I would have been, or the one I would not have been if I hadn’t been born. And so what, if I hadn’t been born.

One person who was not born, for example, was a firstborn son of my family who was under a curse, and was therefore expected in order to see the curse fulfilled in its entirety. And though I’ve already told the story twice — once as fiction, in a short story with false names, “El viaje de Isaac” or “Isaac’s Journey” its title, and again as fact in an article on real names, soberly called “Una maldición” or “A Curse”—not many people will remember it or will have read it, and its most fitting place is here, or so I believe, as if for once, and without my foreseeing it in 1978 or in 1995, I had followed the precept of the eminent short-story writer Isak Dinesen, whom I translated during my time at Oxford and according to whom “only if you are able to imagine what has happened, to repeat it in your imagination, will you see stories, and only if you have the patience to carry them within you for a long, long time, and to tell them to yourself and retell them again and again, will you be capable of telling them well.”

One of my grandmothers came from the very Caribbean Sea where Redonda lies when it does appear on maps or in photographs. She was Cuban, born in Havana; she was named Lola Manera and she was the mother of my mother Lolita. In reality, both she and her father, my great-grandfather, were less Cubans than Spaniards of Cuba, to put it in an understandable and inoffensive way. My great-grandfather was named Enrique Manera and I believe his second surname was Cao (“from Cao the Indian, Montezuma’s lieutenant,” my grandmother’s youngest sister, our Tita María, used to proclaim with folies de grandeur , holding up her index finger); he was a soldier and owned land in Havana.

While still young and unmarried, he was going home on horseback one morning when a mulatto mendicant crossed his path and asked him for alms. He refused and spurred his mount onward, but the beggar managed to stop him by grabbing the bridle, and then pronounced his somewhat baroque and unusually precise curse: “You, your eldest son and the eldest son of your eldest son will all three die when journeying far from your homeland, none of you will reach the age of fifty and none of you will ever have a grave.” My great-grandfather, who paid no attention and shoved the beggar out of the way, told the story at home over lunch and then forgot it (but someone remembered and that’s why it has reached me: perhaps a black nanny or an apprehensive mother, women who are no longer young are always the repositories, and the transmitters). That happened in 1873 when Enrique Manera was twenty-four or twenty-five, two years younger than when he published a little novel I found not long ago — books are always travelling toward me, not sparing me their acquaintance— El coracero de Froeswiller ( Froeswiller’s Cuirassier ), subtitled Recuerdos de la Guerra Franco-Prusiana ( Memories of the Franco-Prussian War ), and printed at number 4 calle del Rosario in Seville, by the press and lithographic studio of Ariza y Ruiz, according to the half title page. Its first lines are very much in the old style: “It was the 15th of July, 1870, and the nocturnal hour of eleven o’clock had just sounded on every church clock in Paris. The capital of the French empire had, at the moment our story begins, a highly strange and exceptional appearance.” And this, apparently, was not the only novel of his to reach the presses, there’s a novelistic family antecedent for me here, an Antillean antecedent. Much later, in 1898, by which time he had been married for half his life to a woman of the Custardoy family with whom he had produced seven offspring (which is why the false name in the story was “Isaac Custardoy”), my great-grandfather Manera decided he would rather not see the Stars and Stripes waving over his island, so he hastily sold off his lands and embarked for Spain — his country, which he may have known only as a name — with his entire family, including my cheerful grandmother Lola who was seven or eight years old at the time, my grandiloquent Tita María, even younger, and the first-born son, considerably older, and also named Enrique. The doctors had advised against this radical measure since my great-grandfather suffered from Ménière’s vertigo and the crossing posed a grave risk to his health. But the soldierly Manera was not inclined to dance attendance on Commodore Schley’s victory over and occupation of the island, so he paid no attention, as he had paid none to the mulatto beggar twenty-five years earlier. Halfway across the Atlantic he suffered a mortal attack of his illness, which struck while he was on deck. He was about to turn fifty and was already far from his homeland — and from the other homeland which he had never seen — when he died, and his body was thrown into the ocean, weighted down with a cannonball.

Читать дальше