But let’s return to 1992. My self-esteem at stake, I immediately alerted my booksellers, G. Heywood Hill and Bell, Book & Radmall and Veronica Watts certainly, and a few others specializing in military matters, though I didn’t know that field very well; I also alerted Eric Southworth and Ian Michael in Oxford, on the unlikely chance that they might run across the damned Crucifix in some secondhand bookshop, and I suppose I also said something to Roger Dobson, who is a true, indefatigable bloodhound, but whose streaks of magnificent good fortune alternate with periods of total loss of nose (and consequent bibliographic famine), so everything depended on whether my mission found him in one phase or the other. I told them how much I was willing to spend, which was quite a lot in relation to the probable cost of an utterly forgotten 1938 book on the Spanish Civil War by an author who was known or of interest to almost no one and whose name, like Gawsworth’s (but more understandably), did not appear in any encyclopedia, dictionary or literary biography, even if some mention of it was made in certain studies of the Spanish Civil War, according to Benet’s information, though not in as many as might have been expected, given his singular, pioneering performance in the airways of the Iberian peninsula— lutos tras otros lutos y otros lutos , sorrow after sorrow and more sorrow — or in the wind that sweeps away the weeks, el viento que se lleva las semanas .

And it was Ben Bass, whereabouts now unknown but then of Greyne House in Avon, who, not much later, worked the miracle and sent me a note in his flowery handwriting to inquire as to whether I would be interested in one copy each of Crucifix and Valley (the other volume by Oloff de Wet, about his imprisonment by the Gestapo), available to me for thirty-five and thirteen pounds respectively, plus shipping and handling. The Crucifix was a little pricey, still I didn’t waste a second on the wretched mails but phoned him right away, wondering all the while why on earth he was asking me if I wanted them rather than sending them to me at once, and before the next dinner with Don Juan Benet and friends both titles were in my clutches and I arrived at the restaurant very pleased with myself, carrying them under my arm and ready to settle the score, many years later, for the humiliation endured by my minuscule, absurd and unmasked comb. I remember Benet’s feigned disappointment as I tossed the books on the table with a movement of the thumb and index finger as if they were cards (“Who knows what vile acts you’ve lowered yourself to in order to get your hands on these rarities so fast, young Marías,” he said, irked and suspicious), which was immediately replaced by an expression of avid curiosity as he expertly thumbed through the newly bagged specimens. Many months later the great bookhunter Ben Bass (who would have to be hunted down himself now) was able to find me a second copy of Cardboard Crucifix , subtitled The Story of a Pilot in Spain , which I could then offer as a gift to Don Juan for the enrichment of his collection and in belated thanks and reward for his generous research and his note for the young Bachelor of Arts. (I’m still waiting for someone to come up with a third copy that I can give to Edkins.) He read it, not long before his death — but we didn’t know that yet — and, like the excerpt cited by Robert Payne, it didn’t strike him as any great thing. I’ll never know if this was his true opinion or just an effort to detract literary merit from this figure I had discovered and thereby make light of my irritating prowess as a digger-up of books. In any case, whatever literary interest the work of Hugh Oloff de Wet might have had, it did not by any means match its author’s biographical and novelistic interest. But I’ll speak of the texts later, perhaps.

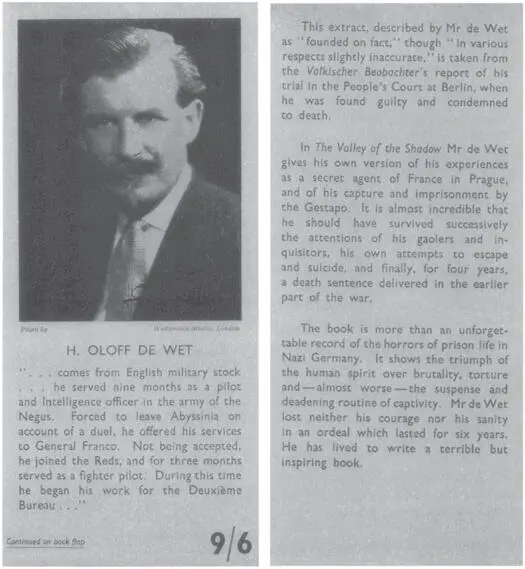

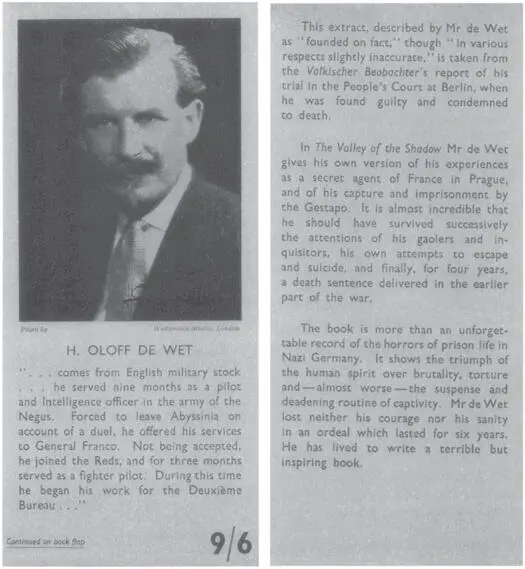

Neither of the two copies — mine or Benet’s — had kept its jacket, so the books bore no information on their author and no description of his work. But The Valley of the Shadow did have its jacket, in good condition, it was published eleven years after Cardboard Crucifix —the Civil War well over and the times thoroughly crushed underfoot, even the Second World War was over — and two years prior to the writer-pilot’s second strange stay in Madrid in 1951, when, of all possible spots, he frequented the Café Gijón, favored haunt of the leisured Spanish literati — or perhaps no one lacked for time back then, it hardly existed, not even Benet, who must have gone there occasionally at the age of twenty-four — and, of all governments in the world, he sought to persuade the predatory but ultra-tightfisted Franco to finance his partisan project in the Carpathians. On the jacket’s front flap were a photograph and a good number of facts, most already reported by Edkins, the protegé. Not all, however.

In the picture, De Wet has the unmistakable look of a British military man, despite his Boer origin — if that was in fact his extraction, and perhaps it wasn’t: the moustache is thick and curly and very well groomed, perhaps he kept its tips upturned by means of an indispensable small, special comb. The long tuft on the chin is a bit jarring, giving him the look of a musketeer or an aspiring cardinal — or Buffalo Bill or Custer — inappropriate to a serious soldier of his time; it suggests an extravagant, roguish side to his character that, taken to an extreme in a foreign country, might give rise to an indecent ponytail, of which there isn’t a glimpse here. Nor does he sport an eyepatch or smoked monocle, and as for the famous earring, unless it adorned the barely visible right ear which is covered in shadow, he seems not to have dared wear it for the portrait done by the Weitzmann Studio, London. He’s dressed as a civilian, which he would have been at that time, and very dapper: the tie is elegant and the jacket’s wool fabric is so excellent that its texture is palpable to the eye. He appears somewhat older than thirty-six (his age then, perhaps) but more because of his robust physique and respectably parted hair than because of any noticeable ravages left by his reckless life. Seeing him so imperturbable, no one would ever guess he had been a prisoner for so long or that he’d been tortured. The clear eyes have a penetrating gaze typical of dark eyes, and neither looks sightless, his features are very correct: a fine-looking man easy to imagine in uniform or in some past century, particularly the seventeenth century, as a corsair or noble or both things together in a not infrequent combination, or in the nineteenth century, but farther away, across the ocean in the Wild West. The signature on the photograph is hard to make out against the dark background.

The text on the front flap of the jacket begins and ends with a set of quotation marks and ellipses; the provenance of these citations is then explained on the back flap. “This extract, described by Mr. de Wet as ‘founded on fact,’ though ‘in various respects slightly inaccurate,’ is taken from the Vôlkischer Beobachter’s report of his trial in the People’s Court at Berlin, when he was found guilty and condemned to death.” And, in a more overtly promotional tone, it continues, “In The Valley of the Shadow Mr de Wet gives his own version of his experiences as a secret agent of France in Prague, and of his capture and imprisonment by the Gestapo. It is almost incredible that he should have survived successively the attentions of his gaolers and inquisitors, his own attempts to escape and suicide, and finally, for four years, a death sentence delivered in the earlier part of the war.” The last paragraph is even more market-minded and not worth bothering with. But it is worth having a look at the article from the Vôlkischer Beobachter of Berlin, dated February 8, 1941, partially reproduced in its original language on pages VI and VII, following the table of contents, the half title, an extremely sinister frontispiece in yellow and black showing a skeletal, chained man seated on the floor of a cell with his eyes shut — a drawing done by De Wet himself — and, filling the entire page that opens the volume, a phrase in quotation marks as if it were a motto or a line of poetry or a Biblical citation that I don’t recognize: “ And still death passed me by ,” it says, in other words, “And death continued to pass me by,” although, with a bit of a stretch, the word still could be understood as an adjective here rather than an adverb, in which case the motto would mean “And silent death passed me by.” But I don’t think so, because “still” in the first sense has, in Hugh Oloff de Wet’s case, all too much significance: the death sentence he received in Berlin was the second of his life, following the one in Valencia five years earlier; he was sentenced to death by the Republicans on whose side he fought in Spain and by the Nazis he fought against in Germany, that is, by both warring parties in the space of a few years. Neither of those two deaths would have been silent. The illustration I described also appears on the jacket and is not the only one in the book, which contains a total of four, all in yellow and black, all sinister, and all done by the volume’s imprisoned mercenary author. The graphic ability thus evinced was the first piece of information that could explain or justify the strange task by which I initially learned of his existence — or only of his name, misspelled — as maker of the death mask of Gawsworth, the poet, who was also Juan I, king of Redonda, Armstrong the beggar, and undoubtedly De Wet’s contemporary, for he, too, was a pilot during those years, under orders from the Royal Air Force in North Africa and the Middle East.

Читать дальше