What I needed now would be further back, behind Charlie’s papers, behind mine. I pushed items forward, ignoring my own life history—school notices, report cards, and swimming certificates from day camp. Fast, Amy. Faster. Clothing receipts clipped together. One group for dresses. Another for shoes. My camp list fastened to the sales slip from the store where we’d bought the Takawanda uniform. Household items: a carpet care guide, an air conditioner warranty, a booklet about the refrigerator. Too recent. I didn’t need to know how to keep meat fresh. I needed to know who my mother was.

A thick folded paper. I lifted it from behind a pamphlet about the washing machine. Marriage Certificate —printed in blue, curlicue letters. It opened like a greeting card, freeing a longer sheet that unfurled. This is to certify that on the seventh of November in the year 1946, the holy covenant of marriage was entered into at Brooklyn, New York, between the Bridegroom, Louis S. Becker, and his Bride, Sonia Kelman Jonas.

I stared at my mother’s name: Sonia Kelman Jonas. Jonas, a name I had never heard. Did that mean Robin was right about my mother being married before? Married to a man whose last name was Jonas? I drew in a sharp breath. If Robin had gotten that right, maybe there really was another daughter. I slipped the marriage certificate back into the box. That baby in Germany. I had to find her.

The screech of a car made me jump. I raced to the window, though my parents’ room didn’t face the street. I would never be able to hide my mother’s stash quickly enough behind her shield of shoes. Again to the closet. Breathe, Amy. Breathe. No sound. Nothing. No one.

The clock on my father’s night table told me she couldn’t be home yet. More papers. Medical bills and health records. Four bundles: my father’s, my mother’s, mine, and Charlie’s. Camp notices from Uncle Ed. My letters from Takawanda, all folded in their envelopes, a rubber band around them.

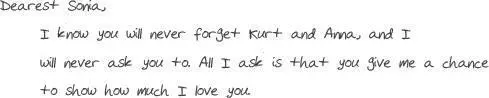

More letters behind those. I pulled out an old-fashioned greeting card, red roses on the front. Inside: Birthday wishes for the one I love. No date, but my father’s handwriting. I was sure of that.

I ran my fingers over the names: Kurt and Anna. Kurt Jonas? My mother’s other husband? And Anna. Was she the daughter?

Another card, more flowers on the front:

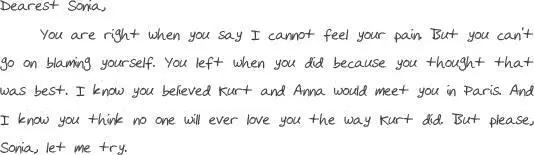

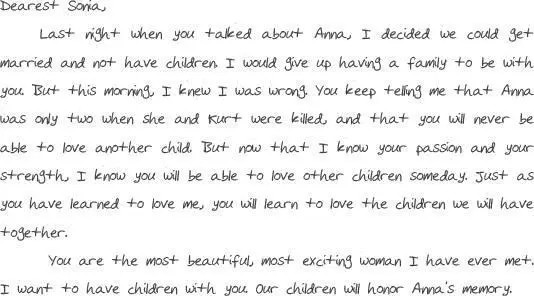

Time stopped while I read the notes my father had written, the tool he had used to slip into my mother’s heart. I couldn’t imagine him speaking those words, saying aloud the thoughts he had penned on pretty cards. I couldn’t mesh the image of my father then with my picture of him now. How could that be the same man who said, “Sonia, enough Sonia,” in an irritated way?

I needed to know more. Why hadn’t Kurt met my mother in Paris? And what about Anna? I read until I found the answer:

I read it again. Our children will honor Anna’s memory. Again and again until I choked on the truth. I could never be good enough for my mother. No matter how I looked and who my friends were, I would never satisfy her. No matter how many “A”s on my report card, my mother wouldn’t want me. She would always want Anna.

A memory ran through my mind. Woolworth’s, the day before camp. The cashier punches the wrong key. My mother asks her name. “Anna,” she says softly, fearful this customer will tell the manager to fire her. But my mother says only, “I’m sorry, dear,” in a voice so soft I don’t recognize it.

Now I knew the truth. There was room for only one child in my mother’s heart. A baby in Germany. Such a little girl filled all the space my mother had for love the way Charlie filled all the space in our house. I couldn’t squeeze in beside Anna. I couldn’t replace her—no matter what I did, no matter how I tried.

I stuffed the cards back into the spot from where I had pulled them. Everything in its place, and a place for every thing. Where was my place, I wondered as I shoved my father’s notes all the way in so their edges rested perfectly on the bottom of the metal box.

That’s when I found the three old photos—two in polished silver frames—buried under papers in the back of the box. I held each to the light, studied them as if I had the power to decipher the past.

The first framed picture gave me Anna: a toddler in a white dress sitting on her mother’s lap. My mother, of course, but not the Mom I knew. Anna’s mother looks like a movie star, with a smile as wide as the ocean she would cross. Anna rests her tiny hand in her mother’s, our mother’s. What could this little girl know about the war that would roll over her family like a bulldozer? And how long after this picture was taken until this photo became all my mother had left of her child?

The second picture: a framed portrait of my mother and Kurt, I guessed. He stands next to her, arm around her waist. Her leading man in a dark suit, the kind my father hated wearing. My mother’s other life: Mom and Kurt and Anna. That’s all she wanted, I thought as I gazed at the man who never made it to Paris. Then I held again the picture of the perfect toddler who claimed my mother’s heart.

A third photo curled at scalloped edges, its sepia image creased but not faded. A man all alone, I saw, as handsome as Kurt, but different somehow. Not a stiff handsome but a confident one. A jacket drapes over the man’s arm, as if announcing he doesn’t need a suit for his image—he’s handsome enough without it. I wondered who he was as I flipped the photo over. No inscription, no name. And whom did he remind me of? It hit me with a jolt. That self-assurance. The intensity of his gaze. The photo made me think of a James Dean magazine picture Patsy had shown me. And it made me think of someone else too. Although it wasn’t a picture of Uncle Ed, it was his face I saw as I studied the photograph.

Yet even more than the ghosts of that day, what happened next haunts me still. Though I have relived this story a hundred times, searching for ways to erase my guilt, I find only one truth—a simple fact: I didn’t hear Charlie’s bus. Not then. Not while I looked again at the picture of Anna and my mother. Anna, that child I could never be. I outlined her face, traced her arm to my mother’s hand.

I don’t know how long the minibus driver waited for someone to come out. How many times did he lean on the horn until I dropped the photo and raced to my brother?

The bus pulled away as Charlie’s feet hit the curb. I ran toward him. “Come on, buddy,” I yelled, my voice too loud. The metal box. The photographs. I had to put them back before my mother got home. “Come on!” I shouted, grabbing Charlie’s hand. “Let’s go!” I pulled him toward the house.

“No!” Charlie cried, struggling to free himself. “No!”

I picked him up and ran with him in my arms. “Go upstairs,” I ordered when I put Charlie down inside the front door. “I’ll be up in a minute.” No scream. No answer. I didn’t wait for him to move.

Back in my parents’ room, I stuffed the pictures into their spot, slammed the lid, pushed the metal box into hiding. The shoes. Brown heels. Navy pumps. What next? White flats, slippers, moccasins. Black shoes. Tan ones.

I turned off the light, closed the closet. No car. No Mom.

Читать дальше