No, something like that just wasn’t possible. It was utter madness; it was uncalled for. As for the wind, old seadogs confirmed that it wasn’t so bad it required such a tragic step. Anyway, who could be sure it would make the wind abate? After all, it was that soothsayer Calchas who’d come up with the idea — and everyone knew how unreliable he was.

I scanned the crowd to find Suzana’s father’s adviser again, but I’d lost him. If I had managed to locate him, in the crazy mood I was in I might have been capable of approaching him and asking out loud: “So it was you, wasn’t it, who gave Suzana’s father that piece of perverse advice? But why did you do it? Go on, tell me why!”

Robert Graves’s book dealt at length with the issue of Calchas. According to the oldest sources, his personality was as puzzling as could be. It was known that he was a Trojan, sent over by Priam with the specific task of sabotaging the Greeks’ campaign. Eventually, though, he’d gone over to the other side, become a turncoat. So you couldn’t avoid wondering whether he was a genuine renegade, or whether his new allegiance was just a strategic cover. It was equally possible, as often happens in circumstances of this kind, that after facing numerous dilemmas in the course of a war whose end was nowhere in sight, Calchas had ended up a double agent.

His proposal to sacrifice Agamemnon’s daughter couldn’t have been a key step in his career. (Let’s not forget that his prophecies, like those of any turncoat, were treated with skepticism.) If he were still secretly in Priam’s service, then obviously he would ask for the sacrifice of the commander’s daughter, to foment further discord and resentment among the increasingly fractious Greeks. But if he’d genuinely gone over to the Greek side, the question would then arise whether he truly believed that the sacrifice would placate the winds (or whatever else: passions, disagreements), and thus permit the fleet to set out.

Whatever he was, a true or sham renegade, an agent provocateur or a double agent, his advice was just too wild, not to say lunatic. A soothsayer, especially in times such as these, must have had many enemies just waiting to use the tiniest of his blunders against him. So if he had made the suggestion to Agamemnon, he would have been sure to lose out in the end.

Far more plausible, therefore, was that Calchas never said anything of the kind, and that the idea of sacrifice had been invented by Agamemnon, for reasons known only to himself. He must have seen how easy it would be to implicate Calchas after the event, to justify his crime in the eyes of enlightened people and to mask its real motive. It was even quite possible that raging winds and so on hadn’t even been mentioned as the fleet was preparing to depart, and that the sacrifice had been performed without a word of explanation. .

The soldiers and civilians of Aulis had converged at the place where the altar had been set up. Maybe invitations had been issued, to prevent the place being overrun. Everyone in attendance must have been on the verge of asking the obvious question: What is this sacrifice? What’s it for? The very absence of a clear answer would have heightened anxiety and fear tenfold.

No, Calchas hadn’t given any advice at all. A prophecy from him would have seemed too dubious, too Machiavellian. But in that case, why had the idea of sacrifice sprung from Agamemnon’s mind like an illumination?

Groups of spectators drifted like ripples lapping rhythmically on the shore toward the places with the best view of the parade, or toward the central stand where the top leaders would take their seats.

I was drifting imperceptibly myself with the same end in view when I saw Suzana. She was in C-2, a little lower down than I was, together with other sons and daughters of the elite.

She was subtly pale, and her indifference could be guessed partly from her profile, and partly from the glistening comb that held up her luxuriant hair. She was staring vacantly in the direction of the band.

Why are they asking for your sacrifice, Suzana? I questioned her silently, with quiet sorrow. What storm are you supposed to appease?

For a brief moment I felt entirely empty. Gripped by the sense of void and exhausted by so many questions, I wondered: Am I not going too far with all these analogies? Isn’t it altogether simpler — a woman naturally pulling back from an affair when an official engagement is imminent? I was the victim of what was, after all, a quite ordinary change of heart. Was my mind not simply trying to give my defeat a tragic dimension that came only from its own nature?

I’d got hold of the word sacrifice and then used it to contrive an analogy I’d taken further than was warranted. I was no better than a novice poet who manages after much effort to spawn a metaphor, then falls for it entirely and constructs an entire poetic work on a foundation no more solid than sand.

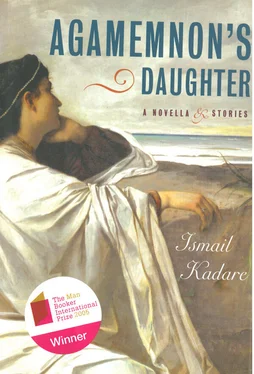

I would never have thought that a sudden perception of a likeness between Suzana and Iphigenia — one of those random, instantaneous illuminations that flash across men’s minds thousands of times every day — could take root in my mind and grow to the dimensions it had now acquired. The identification had become so complete for me that I wouldn’t have batted an eyelash if I’d heard an announcer on radio, on TV, or in the theater introduce “the daughter of Agamemnon, Suzana!” However, the equivalence was also what allowed me to see in an instant a whole new side of the ancient drama, in the light of the present situation of Suzana and her father. It made a new sense of the relations between Agamemnon and the other leaders, of their power struggles and fallback positions, their reasons of state, their use of exemplary punishments, and of terror. .

For a while, my mind seemed intent on casting off a too heavy burden, and made a concentrated effort to de-dramatize the whole thing. But all of a sudden the well-oiled machine in my head jammed, clashed gears, and went into reverse. A massive and fearless NO took hold of my entire being.

No, it couldn’t be that simple! Sure, I was at the end of my rope, I was flailing, but all the same, I was utterly certain that things were not so simple. It wasn’t so much the word sacrifice or Graves’s book that had planted the seed of the analogy in my head. It was something else, something that I could not quite see for the fog surrounding it, but which I could feel quite near. It must be here, in full sight, all I had to do was to shake off a veil that was clouding my vision. . Had not Stalin sacrificed his own son Yakov to… in order to… to be able to say that his own son. . had to share the same destiny.. the same fate… as any Russian soldier? And what had Agamemnon been trying to say two thousand eight hundred years ago? What was Suzana’s father trying to get at now?

My thoughts were interrupted by the sight of her head, swaying between the shoulders of two others. I don’t know why, but the memory of our first meeting suddenly came back to my mind. Portrait of a young girl bleeding. . That’s how it had crystallized in my memory. . It was one afternoon late in the fall. After our first kiss on the couch, she looked me in the eye at leisure, then said with quiet composure: I love you. She maintained her quizzical stare, as if checking to see that I’d understood her. She needed only a sign from me to offer proof of what she’d just said, and when I responded — rather hesitantly, as I was somewhat taken aback at the prospect of such an easy triumph — “How about lying down?” she got up right away and, with the same placid manner as she had spoken, got undressed.

I followed her orderly gestures. Her lace lingerie appeared when she took off her dress, and when she pulled down her tights her smooth white legs came into view. I got up from the couch and kissed her as cautiously as if she were sleepwalking, and pressed a bunch of her hair to my right cheek. I like expensive women … I mumbled, without knowing then or since whether “expensive” referred to her Western underwear, to the valuable comb that embellished her hair, or to the ease and simplicity with which she offered herself.

Читать дальше