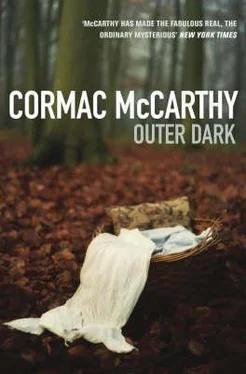

Cormac McCarthy - Outer Dark

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Cormac McCarthy - Outer Dark» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2007, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Outer Dark

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Outer Dark: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Outer Dark»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Outer Dark — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Outer Dark», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I ain’t got nary garden, she said.

Well anyway you let him worry about it.

Yessir, she said.

He leaned back again. It was very quiet in the room. The light waxed and waned and the squatting shape of the windowsash came and went on the wood floor like something breathing. Are you married? he said.

No, she said. Then she looked up and said: I mean I ain’t now. I was but I ain’t now.

You a widow then?

Yessir.

Well that’s a pity. Young woman like you. You got any babies?

One.

Yes.

The room was growing darker. A gust of damp air moved upon them and the frayed lace curtains at the window lifted.

Looks like we’re fixing to have some rain, he said.

But it had already started, the glass staining with random slashes, the hot stone ledge steaming.

We get a lot of rain here in the fall, the lawyer said. After it’s too late to do anything any good.

They sat in the gathering dark and watched the rain. After a while the lawyer put his feet down again and rose from the chair. That’s him now, he said.

She nodded. He went to the door and peered out. She could hear someone stamping and swearing their way up the stairwell.

Looks like you got a little damp there, John, the lawyer said.

The other one said something she couldn’t hear.

Well you got one waiting on you.

He looked through the door. A short heavy man with moustaches from which water dripped, peering above the rim of his fogged spectacles. How do, he said.

Hidy, she said.

Just come on in over here. He disappeared and she rose and crossed the floor before the lawyer and gave him a little curtsying nod, ragged, shoeless, deferential and half deranged, and yet moving in an almost palpable amnion of propriety. I sure thank ye, she said.

The lawyer nodded and smiled. That’s all right, he said.

When she entered the doctor’s office he had his back to the door, shaking out and hanging up his wet coat on a rack. He turned, brushing the dampness from his shoulders, his shirt plastered transparently to his skin there.

Whew, he said. Well now. What was your trouble young lady?

She looked behind her. The lawyer had closed his door. She could hear the rain outside and it was dark enough to want a lamp.

Over here, he said. Take a seat.

Thank ye, she said. She took the chair near his desk and sat, primly, tucking her feet beneath the rungs. When she looked up he was sitting at the desk mopping furiously at the lenses of his spectacles with a handkerchief.

Now, he said. What was it?

Well, it’s about my milk.

Your milk?

Yessir. Kindly.

You ain’t fevered are you?

No. It ain’t that. I mean I don’t know. It’s my own milk I meant.

Yes. He leaned back and ran one finger alongside his nose, the glasses poised in midair. You’re nursing a baby. Is that what it is?

She didn’t answer for a minute. Then she said: Well, no. She stopped again and looked up at him for help. He was looking out the window. He turned back and put the glasses on his nose.

All right, he said. First: Are we talking about cow milk or people milk?

People, she said.

Right. Yours?

Yessir.

All right. You have been nursing a baby then.

No, she said. I ain’t never nursed him. That’s what’s ailin me.

You had a baby?

Yessir.

When?

Early of the spring. March I believe it was.

That’s six months ago, the doctor said.

Yes, she said.

The doctor leaned forward and laid one arm out upon the desk and studied his hand. Well, he said, I reckon then you must of had a wetnurse. And now you want to know why you never had any milk. After six months.

No sir, she said. That ain’t it.

It’s not getting any easier, is it?

No sir. They smart a good bit.

You never had any milk.

I never needed none but I had too much all the time.

He looked at the hand as if perhaps it would tell him something and then perhaps it did because he looked up at her and he said: What happened to the baby?

It died.

Of late?

No. The day it was borned.

And you still have milk.

It ain’t that so much. I don’t mind it. It’s that they startin to bleed. My paps.

Then they were both quiet for a long time. The room was almost dark and they could hear the steady small slicing of the rain on the glass and the spat of it on the stone sill. He spoke next. Very quietly. He said: You’re lying to me.

She looked up. She didn’t seem surprised. She said: About what part?

You tell me. Either about your breasts or about the baby. No woman carries milk six months for a dead baby.

She didn’t say anything.

Do you want to show me?

What?

I said do you want to show me? Your breasts?

All right, she said. She stood and unbuttoned the shift at the neck and slid the shoulders down so that she was standing with her arms pinioned in the rotten cloth. It was all she wore.

Yes, he said. All right. I’ll give you something for that. It must be very painful.

She worked the dress back over her shoulders and turned to do the buttons. It smarts some, she said.

Have you been pumping them? Milking them?

No sir. They just run by their own selves.

Yes. You should milk them though. Where is the baby?

I don’t know. I mean I ain’t seen it since it was borned but I believe I know who’s got it if I could find him.

And when was it? That it was born.

I believe it was in March but it could of been April.

That’s not possible, he said.

Well it was March then.

Look, the doctor said, what difference does it make if it was later than that? Like maybe in July.

I wouldn’t of cared, she said.

The doctor leaned back. You couldn’t still have milk after six months.

If he was dead. That’s what you said wasn’t it? She was leaning forward in the chair watching him. That means he ain’t, don’t it? That means he ain’t dead or I’d of gone dry. Ain’t it?

Well, the doctor said. But something half wild in her look stopped him. Yes, he said. That could be what it means. Yes.

I knowed it all the time, she said. I guess I knowed it right along.

Yes, he said. Look, let me give you this salve. He swung about in his chair and rose and unlocked a cabinet behind his desk. He studied the interior for a moment and then selected a small jar and closed the cabinet door again. Now, he said, turning and holding up the jar. I want you to put this on good and heavy and keep it on all the time. If it wears off put more. And you’ll have to pump them even if it hurts. Try it a little bit first. He slid the jar across the desk to her and she took it and looked at it and sat holding it in her lap.

Come back in a couple of days and tell me how you’re doing.

I don’t know as I’ll be here, she said.

Where will you be?

I don’t know. I got to get on huntin him.

The baby?

Yessir.

When did you see it last? You said you never nursed it.

I ain’t seen it since it was borned.

Then what was the part you lied about?

Well. About it bein dead.

Yes. What did happen?

He said it was puny but afore God it weren’t puny a bit.

And what happened then?

We never had nothin nor nobody.

You’re not married are you?

No sir.

And what happened? Was the baby given away?

Yes, she said. I never meant for him to do that. I wasn’t ashamed. He said it died but I knowed that for a lie. He lied all the time.

Who did?

My brother.

The doctor leaned back in the chair and folded his hands in his lap and looked at them. After a while he said: You don’t know where the baby is?

No sir.

Below them in the street cattle were being driven lowing through the rain and the mud.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Outer Dark»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Outer Dark» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Outer Dark» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.