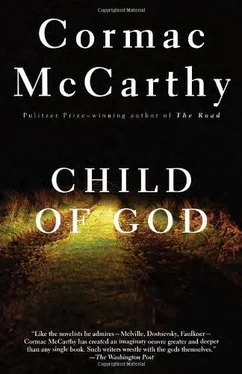

Cormac McCarthy - Child of God

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Cormac McCarthy - Child of God» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1993, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Child of God

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1993

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Child of God: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Child of God»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Child of God — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Child of God», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Someone was tying a rope about Ballard’s arm. The steel cable slipped over his neck and rested on his shoulders. It was cold, smelled of oil.

Then he was walking up the hill toward the saw-mill. They helped him along, down the skids, stepping carefully, the flames from the bonfire stringing them in a ragged shadowshow across the upper hillside. Ballard slipped once and was caught up and helped on. They came to rest standing on an eight by eight above the sawdust pit. One of the men was boosted up to the overhead beams and handed up the slack end of the cable.

They ain’t got him doped up have they, Ernest? I’d hate for him not to know what was happenin to him.

He looks alert enough to me.

Ballard craned his head toward the man who’d spoke. I’ll tell ye, he said.

Tell us what?

Where they’re at. Them bodies. You said if I’d tell you’d turn me loose.

Well you better get to telling.

They’re in caves.

In caves.

I put em in caves.

Can you find em?

Yeah. I know where they’re at.

BALLARD ENTERED THE HOLLOW ROCK that used to be his home attended by eight or ten men with lanterns and lights. The rest of them built a fire at the mouth of the cave and sat about to wait.

They gave him a flashlight and fell in behind him. Down narrow dripping corridors, across stone rooms where fragile spires stood everywhere from the floor and a stream in its stone bed ran on in the sightless dark.

They went on hands and knees between shifted bedding planes and up a narrow gorge, Ballard pausing from time to time to adjust the cuffs of his overalls. His entourage somewhat in wonder.

You ever see anything to beat this?

We used to mess around in these old caves when I was a boy.

We did too but I never knowed about thisn here.

Abruptly Ballard stopped. Balancing with one arm, the flashlight in his teeth, he climbed a ledge and went along it with his face to the wall, went upward again, his bare toes gripping the rocks like an ape, and crawled through a narrow fissure in the stone.

They watched him go.

Goddamn if that there ain’t a awful small hole.

What I’m thinkin is how we goin to get them bodies out of here if we do find em.

Well somebody shinny up there and let’s go.

Here Ed. Hold the light.

The first man followed the ledge and climbed up to the hole. He turned sideways. He stooped.

Hand me that light up here.

What’s the trouble?

Shit.

What is it?

Ballard!

Ballard’s name faded in a diminishing series of shunted echoes down the hole where he had gone.

What is it, Tommy?

That little son of a bitch.

Where is he?

He’s by god gone.

Well let’s get after him.

I cain’t get through the hole.

Well kiss my ass.

Who’s the smallest?

Ed is, I reckon.

Come up here, Ed.

They boosted the next man up and he tried to wedge his way into the hole but he would not fit.

Can you see his light or anything?

Shit no, not a goddamn thing.

Somebody go get Jimmy. He can get through here.

They looked about at one another assembled there in the pale and sparring beams of their torches.

Well shit.

You thinkin what I am?

I sure as hell am. Does anybody remember how we came?

Oh fuck.

We better stick together.

You reckon there’s another entrance to this hole he’s in?

I don’t know. You reckon we ought to leave somebody to watch here?

We might never find em again.

There’s a lot of truth in that.

We could leave a light just around the corner here where it would look like somebody was a waitin.

Well.

Ballard!

Little son of a bitch.

Fuck that. Let’s go.

Who wants to lead the way?

I think I can find it.

Well go ahead.

Goddamn if that little bastard ain’t played us for a bunch of fools.

I guess he played em the way he seen em. I cain’t wait to tell these boys outside what’s happened.

Maybe we better odd man out to see who gets the fun of tellin em.

Watch your all’s head.

You know what we’ve done don’t ye?

Yeah. I know what we’ve done. We’ve rescued the little fucker from jail and turned him loose where he can murder folks again. That’s what we’ve done.

That’s exactly right.

We’ll get him.

He may of got us. You remember this here?

I don’t remember none of it. I’m just follerin the man in front of me.

FOR THREE DAYS BALLARD explored the cave he’d entered in an attempt to find another exit. He thought it was a week and was amazed at how the batteries in the flashlight kept. He fell into the custom of napping and waking and going on again. He could find nothing but stone to sleep upon and his naps were brief.

Toward the end he would tap the flashlight against his leg to warm the dull orange glow of it. He took the batteries out and put them in again the hind one fore. Once he heard voices somewhere behind him and once he thought he saw a light. He made his way toward it in darkness lest it be the lights of his enemies but he found nothing. He knelt and drank from a dripping pool. He rested, drank again. He watched in the bore of his flashbeam tiny translucent fish whose bones in shadow through their frail mica sheathing traversed the shallow stonefloored pool. When he rose the water swung in his wasted paunch.

He scrabbled like a rat up a long slick mudslide and entered a long room filled with bones. Ballard circled this ancient ossuary kicking at the ruins. The brown and pitted armatures of bison, elk. A jaguar’s skull whose one remaining eyetooth he pried out and secured in the bib pocket of his overalls. That same day he came to a sheer drop and when he tried his failing beam it fell down a damp wall to terminate in nothingness and night. He found a stone and dropped it over the edge. It fell silently. Fell. In silence. Ballard had already turned to reach for another to drop when he heard far below the tiny spungg of the stone in water like a pebble down a well.

In the end he came to a small room with a thin shaft of actual daylight leaning in from the ceiling. It occurred to him only now that he might have passed other apertures to the upper world in the nighttime and not known it. He put his hand up into the crevice. He pried. He scratched at the dirt.

When he woke it was dark. He felt around and came up with the flashlight and pushed the button. A pale red wire lit within the bulb and slowly died. Ballard lay listening in the dark but the only sound he heard was his heart.

In the morning when the light in the fissure dimly marked him out this drowsing captive looked so inculpate in the fastness of his hollow stone you might have said he was half right who thought himself so grievous a case against the gods.

He worked all day, scratching at the hole with a piece of stone or with his bare hand. He’d sleep and work and sleep again. Or sort among the dusty relics of a nest seeking a whole hickory nut among the bone-hard hulls with their volute channels cleanly unmeated by woodmice, teeth precise and curved as sailmakers needles. He could find none, nor was he hungry. He slept again.

In the night he heard hounds and called to them but the enormous echo of his voice in the cavern filled him with fear and he would not call again. He heard the mice scurry in the dark. Perhaps they’d nest in his skull, spawn their tiny bald and mewling whelps in the lobed caverns where his brains had been. His bones polished clean as eggshells, centipedes sleeping in their marrowed flutes, his ribs curling slender and whitely like a bone flower in the dark stone bowl. He’d cause to wish and he did wish for some brute midwife to spald him from his rocky keep.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Child of God»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Child of God» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Child of God» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.