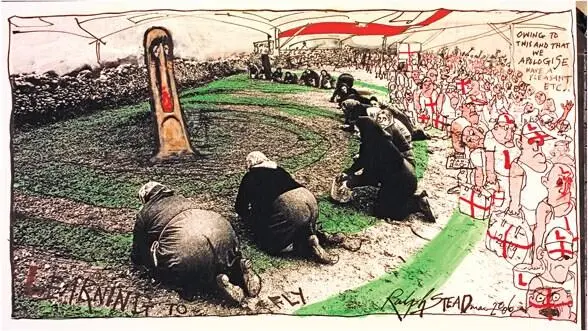

I myself am a recent convert to the cult of Rianare, having flown to Cork at the weekend on a low-cost airline. In Ireland the God is known as ‘Ryanair’ (Rían-àr in the original Gaelic), and his devotees, despite the anathema pronounced on them by the Cardinal Primate of All Ireland, are quite as numerous and fanatical as those in southern Italy. Personally, I didn’t know what to expect when I started on this new, spiritual path. I had been warned that in return for a seat Ryanair demanded exorbitant mortification on the part of his suppliants. There would be a twenty-mile walk from the departure lounge to the gate. Indeed, very likely there would be no gate at all, simply a gash in the aluminium skin of the terminal building, through which passengers would be bodily hurled on to the concrete apron.

Once on the plane — already battered and bruised — I would find no seats, as such, only straps from which to hang. When turbulence came, us dangling punters would collide with each other like ball-bearings in a Newton’s cradle, setting in motion the most inappropriate collisions, and even spontaneous acts of congress. No wonder, I thought, the Cardinal Primate takes such a dim view. Moreover, there would be no strap allocation, for on cheap flights it’s every man, woman and even child for themselves. In the event things weren’t that bad at all. There were seats, and, as none of these were secured, instead of finding myself sandwiched beside one of my own, needy offspring I instead plumped down and discovered that my thigh was melded against that of Kate Moss, the internationally renowned model and demi-mondaine.

Surprised? I didn’t even know she was Irish. It transpired that Moisty — as she is familiarly dubbed — flies back and forth to West Cork with disarming frequency. As she vouchsafed to me, the flights are now so cheap that it’s more cost effective for her to hire a babysitter in Bantry and have them flown over for the evening, than to engage one on Primrose Hill. I spoke to a couple of other parents of young children on the flight, and they said the same thing: Ryanair brought families closer together; now Nan could sit, chewing a quid of tobacco, and singing ‘The Croppy Boy’ in the corner of their Danish Modern kitchen in Clifton, for the price of a loaf of soda bread. Mind you, that isn’t for the price of a loaf of soda bread actually on a Ryanair plane; that costs £27,609.43 (€40,653.29).

Who are we environmentalist Cassandras to deny these simple folk their consanguinity admixed with aviation fuel? What perverse ideology would dare to tear grandchild from grandmother, stag night from Cork bar? So what if the improved familial relations of today are ruining it all for succeeding generations? At least those future generations will have had well-adjusted parents. And anyway, the airspace of today is not the airspace of yesteryear. That was a moneyed preserve, accessible only to the super-rich, who in a very important sense owned it. Now the sky belongs to all, and is like unto an illimitable, blue moorland, across which the masses have the inalienable right to roam.

Frankly, this is all just as well, because once you actually arrive in Ireland you will find yourself subject to a most astonishing reversal: you may have been able to fly hundreds of miles with utter abandon, but at ground level the Emerald Isle sets up fierce resistance to the idea of anyone daring to stray off the beaten track. Since 1995 something called the ‘Owners Liability Act’ has been in force. This makes property owners legally obliged to compensate walkers for any accidents that happen to them on their land — even if these occur on public rights of way. Needless to say, this has made Irish landowners — never that keen on unconstrained roaming in the gloaming — positively Stalinesque, exiling ramblers from their land with brutal alacrity. Only in the burgeoning cult of Rían-àr can the people find succour.

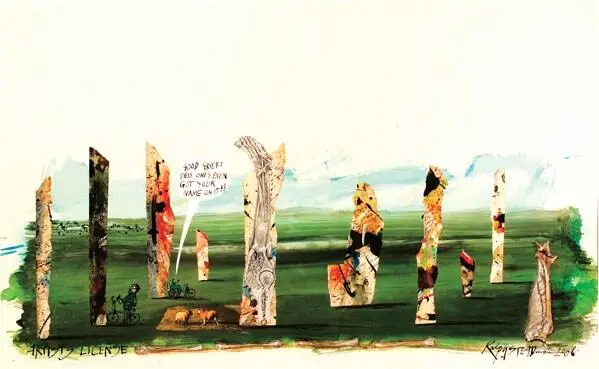

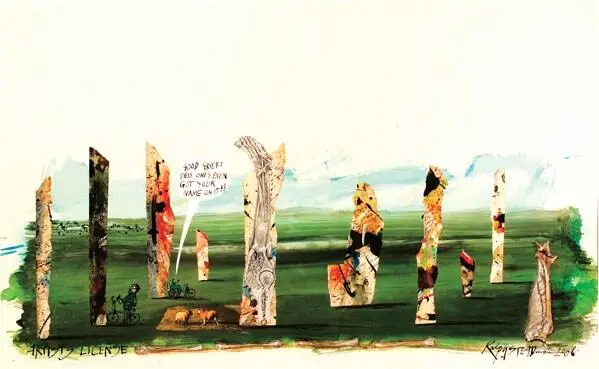

I suppose, if we were honest, by the time we reached Papa Westray both Antony and I were already just a little bit weirded out. It had been a beautiful day, and we’d cycled up the length of the larger Orcadian island of Westray, stopping only to boil up cockles on a perfect white sand beach and visit an archaeological site at the Knowe of Skea. Here affable archaeologists (mind you, have you ever met one who wasn’t affable?) gave of their time to tell us about the dig. It was an Iron Age sacred site of some kind, the corpses of 127 people bound and interred in the walls of a series of buildings used for metalworking. ‘Basically,’ our guide told us, ‘these people were metal-bashing while granny rotted in the wainscoting.’

There was no one besides us on the ferry across to Papay, as it’s locally known. Antony chatted with our genial Charon, while I observed the bank of sea mist, which, having remained offshore throughout the day, was now oozing in. At Moclett Pier a lady was waiting in her car. She wore a blue tunic and took receipt of a prescription from the ferryman. ‘Do you want a lift up to Beltane House?’ she asked, but we declined. Fiona was, it transpired, our hostess, as well as the district nurse. ‘And will chicken be all right for supper, because he’s got it on?’ Chicken, we conceded, would be fine.

We traversed a dwarfish golf course with only one hole and crossed by the shore of the Loch of St Tredwell. This was the uttermost end of Orkney, with nothing due north of it save for Fair Isle, where men are men and jumpers are nervous. Papay is a diminutive island, four miles long and barely a mile wide in places, but it supports a big history. St Tredwell, the remains of whose chapel stand beside the loch, was one of the ‘holy virgins’ who accompanied St Boniface on his mission to convert the Picts. Apparently, when some venal fellow saw fit to compliment the nascent saint on her fine eyes, she responded by tearing them out and sending them to him stuck on a bodkin. How’s that for anti-vanity!

There’s Tredwell and there’s the Traills, who for centuries were the lairds of Papay. Their big pile, which weights down the middle of the island with its austere vernacular chunkiness, is dubbed ‘Holland’, because of some Traill’s dubious notion that this green lozenge resembled the fertile polders of the Netherlands. The Traills were your typical vile, Highland landowners, racking the rents of their tenants and putting them to work on the noisome and foul business of kelp-making. The Traills are long since gone, but their legacy remains all over the island in the form of abandoned crofts, many of them falling to pieces. Of course, Antony can’t see an abandoned croft without wanting to re-tenant it.

So, Antony rummaged around in a tumbledown cabin, while I sat and smoked. He emerged with some lurid recipe books from the 1950s, featuring Day-Glo illustrations of vegetarian cutlets. Oh, and there was also a needlework guide. Finally we reached Beltane House, a B&B-cum-hostel run by the island co-op, to find that ‘he’, our culinary nemesis, was waiting with the chicken. Lots of chicken and lots of gravy — boat after boat of it sailed to our table and slathered itself over croft-sized mounds of potatoes and chapels of roast fowl. After a wedge of gateau leaking refined sugar, we called for mercy and set out to burn some of the calories off.

The sea mist had rolled right in by now, and the windsock at the dinky little airport (the shortest scheduled flight in the world is from Westray to Papa Westray: two minutes), hung limp in the gloaming. Apart from ‘Him’ and ‘Her’ at Beltane House we’d met no one on the island. We wandered through the farms, past old threshing barns. Even the cattle in the fields looked like isolated figures: all of them cut off from the herd. At this latitude it never really gets dark at night, only eerie. We came upon St Boniface’s, an austere little kirk on the seashore, four-square, its churchyard planted thick with carious headstones.

Читать дальше