On I slithered, through a watery world carved by the tail of the Mersey as it lashed in its flood plain. Past the fat-bellied deities of the Runcorn Power Station cooling towers, where I could hear metal being tortured behind closed doors, while steam clouds of preternatural brightness plumped above the reed beds. I may wax lyrical — but then why shouldn’t I? When I joined the ship canal itself, at Warrington, I felt my wheel fitting into a groove scoured out over centuries by the most historically significant motive forces Eurasia has ever known.

The ship canal: a pre-rail, eotechnic form of transport, force-fed by coal and steel. Manchester: the manufactory of the world for a hundred years. Liverpool: its port — and the line of the canal — extended in space across the Atlantic to America, like a water spout from a chthonic past shooting into the post-industrial future. And it was, of course, deserted, except for a man walking a Scotty dog under a golfing brolly, his feet crackling on empty White Lightning bottles, while a hubcap gleamed on the eroding bank.

At a massive set of locks, lowered over by a red-brick building bearing the optimistic legend ‘New World Gas Cookers’, I left the ship canal and followed the route of a dismantled railway across country to Altrincham. The rain cleared and from the embankment I could see jets hurled up by Manchester Airport to spear the cloud cover. I joined the Cheshire Ring Canal for a few miles, before, at Sale, sodden and chapped, deciding to chuck the proverbial towel in. I folded up the bike and boarded a tramcar, which ran up on an elevated section through the outskirts of the conurbation, before, at Old Trafford, suddenly dipping down to the ground and merging with the road traffic.

It was a fitting end to such a journey: the seeming-train transforming into a bus. I had traversed mighty canals that were now weedy backwaters, and the muddy sloughs of defunct iron roads. This part of the world was not a landscape at all, but a palimpsest, worked over again and again by the busy hands of humankind. At dinner that night, in a Thai restaurant, I announced to my five Mancunian companions — none of whom, so far as I know, were hard of hearing — ‘I cycled from Runcorn to Sale today.’ And this remark went blissfully unacknowledged.

Forgive me if I’ve written this before, but as a man — or a woman, or an hermaphrodite for that matter — grows older, his/her ability to recall things, thankfully, gets hazy. Besides, this was one of the formative experiences of my life, so why not come at it from another angle?

When I worked as a corporate publisher in the 1980s I went to pitch my services to Weetabix, who had their factory in Kettering in the East Midlands. It was the usual tedious drive up into the heart of England, my suit jacket dangling from a hook behind my ear, my face frozen in that dreadful rictus which is engendered by loud in-car entertainment, nicotine, Nescafé and gnawing frustration. When I got to the outskirts of the town I pulled up, and, stepping out of my regulation Ford Sierra, I was assailed by a great wave of wheatiness that engulfed me, stoppering up my mouth and nostrils with the essence of an thousand thousand breakfasts.

Blimey! I thought (these were innocent days, the whole culture existed before the watershed), what can it be like to grow up in this cerealville? As a child, you must believe that this intense, foody atmosphere is natural, then, when at last you reach your maturity, and travel to some other burgh — say Redditch — be altogether perplexed by its absence.

Ever since I’ve thought of the Midlands as a region dominated by these mono-product towns: Birmingham for cars, Nottingham for shoes, Bourneville for chocolate, Stafford for pottery. The waist of Olde Englande is cinched by a belt studded with these buckles, and to travel around it is to find yourself in the tarmac aisles of some grossly elongated cash-and-carry. Not that you’ll be carrying many cars away from Birmingham nowadays; indeed, so far has the second city shed its status as the Detroit of England that the centre is now almost entirely pedestrianised. Pedestrianised and elevated: the other evening (the first balmy one of summer), I walked all the way from the trendy restaurant area around the canal at Brindley Place, to my hotel by St Philip’s Cathedral, without even setting foot at ground level. Doubtless out at Longbridge the rust never sleeps, while tumbleweeds blow across Spaghetti Junction.

The following morning I left for Lichfield, and sat in the jolting, sunlit carriage assailed by an inane in-train television channel. Who would’ve thought that the future would be so technologically scrambled? Yes, we anticipated such things in the 1970s, but we thought they’d come together with jet packs, meals-in-a-pill and eternal life. Instead we get stainless-steel automated toilets, embedded in the same old shitty railway platforms.

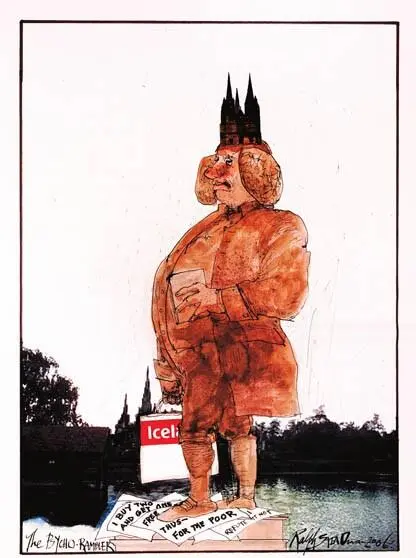

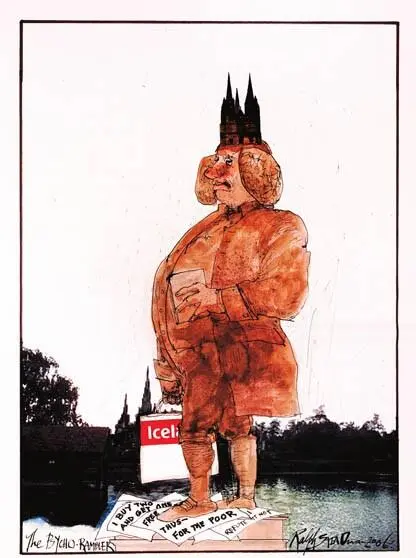

Such meditations were fit meat for Lichfield, where the pollution-corroded fangs of the perfect bijou Gothic cathedral gnawed at the sky and gnashed on the winding, Tudor-fronted streets. Lichfield being a carpet town, there was its most famous son, Samuel Johnson, looking gloomy, dropsical and depressed, while apparently sitting atop a pile of cheap rugs. On the plinth of the statue which was surrounded on all sides by the carpet market was this epigram of the Great Cham: ‘Every man has a lurking wish to appear considerable in his own land.’

‘What a deep pile of. .’ I muttered to myself, as I wandered off to find some cheese in a nice olde cheese shop. But there was none to be had anywhere. I consulted an ancient crone of the diocese, who informed me: ‘You’ll have to go to Iceland.’ And that, in a non-recyclable plastic shell, is the very rub of modern Middle England: you always have to go to Iceland.

At the cathedral a genial beadle told me: ‘We’ve a lot of children in today, but I’m sure they won’t bother you and nor,’ his eyes hardened into paedophilia-seeking devices, ‘will you bother them.’ Frankly, I would’ve been hard put to bother them, because there were hundreds of the little blighters. Whole choirs of little seats had been lain out in the nave, the transept, the chapels, and upon them lessons were taking place. What a joy it was to see this magnificent building fully tenanted, instead of vacuous with the absence of God.

I plodded on out of Lichfield as the day heated up. On and on along the canal heading north. On and on past fields of alien, oily rape. On and on, with only my overheated brain for company. Towards late afternoon I crossed over Watling Street and reached the outskirts of Burton-on-Trent, only to be assailed by a great wave of maltiness, a farinaceous swell that engulfed me, stoppering up my mouth and nostrils with the essence of an thousand thousand pints of lager. The great steel vats of the Coors brewery scintillated in the sunshine. ‘What must it be like,’ I mused, ‘to grow up in this beerville, waiting your entire childhood for chucking-out time?’

Shown here are a group of peasant women Ralph caught on camera during his recent sojourn in the rural fastness of Puglia. According to a local ethnographer (who Ralph managed to corner in a bar, then strong-arm until he divulged), the ancient crones are worshipping a totemic carving of Rianare, the God of Cheap Plane Flights. Their belief is that if a suitable offering is presented to Rianare (a garland festooned with polished olive stones is usually enough), he will bless the donor with a £27.49 return flight to Stansted; or Luton, or Gatwick — and possibly even the East Midlands Airport. Anywhere, in fact, so long as it isn’t Heathrow, the passenger wasn’t born in a leap year, and their hold baggage doesn’t contain more socks than pants. (Pants surcharge is £4,578.23 per pair.)

Читать дальше