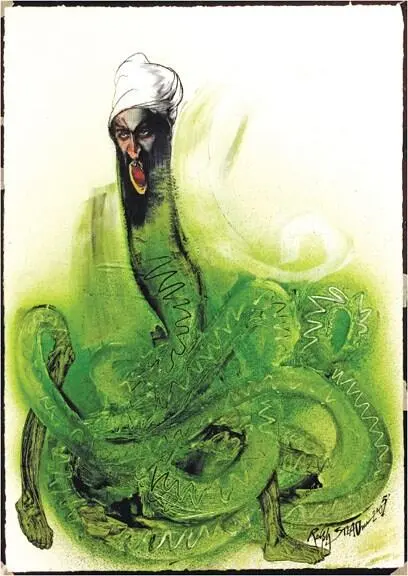

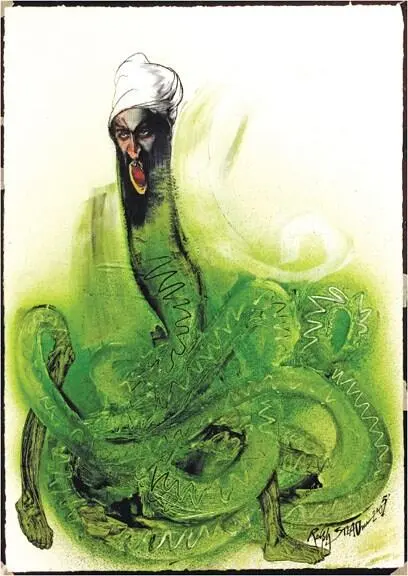

Still, he and his associates do have one implacable idea: that by wreaking death and destruction on the infidel they will awaken the torpid Muslim masses and force them to overturn their corrupt rulers and impose the rule of God. Getting captured would put a severe crimp on this plan, for, so long as bin Laden is at liberty, no matter how circumscribed his personal influence, he acts as a potent figurehead for every ragged man who raises a rocket-propelled grenade launcher to his shoulder and lets fly. His face is on a million T-shirts, his name is constantly on the lips of Iraqi insurgents and Hamas fighters. When Al Jazeera receives a scratchy videotape or a creaking recording, his omniscience is only confirmed. Nothing is more fitting than that he should be thus: exiguous, wavering, a smoky djinni billowing above the apocalyptic battlefield.

We want him up there in the debatable lands of north-western Pakistan, the savage landscape that swallowed the Great Gamers and spat out the bones. We picture him guarded by fearsome Pathan tribesmen armed with fifteen-foot-long rifles. Although the chances are he’s probably in Reigate. In Reigate and spending his days shuttling across to Crawley General Hospital for a little gentle kidney dialysis. In Reigate, and far from bothering with a shave and a haircut — let alone radical cosmetic surgery — I bet he still looks exactly the same. ‘Who’s that old geezer then?’ ask those who see him sitting on a park bench, or abrading a scratch card. ‘He don’t ’alf look like that bin-whatsit bloke.’ To which his unwitting protectors reply: ‘Oh him? He’s harmless enough — he drinks down the Chequers and plays bowls in the afternoon.’ Hardly what you’d expect — his entire disappearing act resting on phenomenal chutzpah.

We want fugitives though. We like the idea that Lord Lucan, Butch Cassidy and Martin Bormann are playing gin rummy at a beachfront bar in Mombasa. We urge the bad guys on across the Rio Grande; we supply plane tickets to sarf London faces so they can take off for the Costa del Crime. So long as there are fugitives in the world there remains a certain mystery at its margins; all has not been discovered, snooped into, X-rayed by the CIA. The capture of the fugitive is always intolerably prosaic — in an instant he is transformed from a figure of dreadful potency into an unshaven old man with plaster dust in his unkempt hair. This phenomenon is perfectly illustrated by Saddam Hussein, and ever since his capture the media have been willing him to assume his former guise: the coal-black moustache of tyranny.

Thus flight is only a good career move if you’re prepared to stay on the run indefinitely. Don’t end up like Kim Philby, whingeing and drunk in Moscow; or Ronnie Biggs, bartering your freedom for the National Health; or Adolf Eichmann, displayed in a plastic box in Tel Aviv, and such a prosaic figure that Hannah Arendt coined the expression ‘the banality of evil’ purely in order to describe his showroom-dummy features. Better not to go on the run at all; be like Slobby Milošević, throw your arms up, make them build you a special courtroom in the Lowlands, then spend the next few years on your demented high horse, forcing them to spend billions simply in order to give you a slap.

We’re always keen to welcome new talent in this column, so it’s with great enthusiasm that we introduce to you a great big black cloud of hydrocarbons floating over southern England. Black Cloud — as we’ll call it for convenience — first appeared on the morning of Sunday 11 December 2005. My friend Louisa was staying about two miles from Hemel Hempstead when at 6.00 a.m. she was awoken by an earth-shattering explosion: ‘The whole house shook on its foundations, some of the windows broke. When we got up and looked to the west there were giant flames lighting up the pre-dawn sky. Naturally our first assumption was that this was a terrorist attack, but when we turned on the TV we discovered that this oil depot had caught fire.’

The Buncefield Oil Depot to be precise. Crazy name — crazy great inland lagoon of highly inflammable petrol and aviation fuel, hundreds of thousands of litres of the gunk. I find the name itself highly suggestive, ‘bunce’ being City traders’ slang for the money they cream off the top of a deal. So a field of bunce suggests a veritable patina of profit dirtying every little living thing. Still, I doubt it’s an image that will appeal to the residents of Leverstock Green, who had to be evacuated from their homes as the huge death’s head of smoke wobbled up into the sky.

Over the next couple of days while the fire burnt itself out we were treated to a magnificent photo shoot of Black Cloud as it struck various attitudes above the land: Black Cloud boiling and bloody in the immediate vicinity of the burning tanks; Black Cloud lowering and minatory over the bog-standard 1960s semis surrounding the depot; Black Cloud seen from a helicopter at 5,000 feet, a thick discharge of poison rendering the very curvature of the earth itself unstable and problematic. Eventually we were shown a satellite image of Black Cloud hanging over the entire southern half of Britain, a filthy aorta beating in the heart of our green and unpleasant land.

In a year which has been marked by some really exciting disasters, both man-made and natural (although this is, in my view, a specious distinction), it’s a great thrill to welcome the greatest explosion in peacetime Europe. It took 150 fire-fighters using 32,000 litres of water every minute to put out the blaze, while they blanketed the storage tanks with a winter wonderland of chemical foam. Up in Black Cloud itself were the equivalent of 25 per cent of a single day’s hydrocarbon emissions in the UK.

Put like that it doesn’t sound so impressive after all. I mean to say, the spectacle of health official after environmental wonk popping up on our television screens to warn us of the coming sooty Armageddon acquired a certain risible character when the camera cut away to reveal the Hemel Hempsteaders still tootling about in their hydrocarbon-emitting bumper cars immediately beneath the Black Cloud itself.

On the Friday after the explosion at the depot I couldn’t resist going to have a look at Black Cloud’s theatre of operations. I told my brother I was taking him on a ‘mystery walk’ in the London environs, and conducted him on to the train at Euston while he averted his eyes from the signboards and hummed during announcements. Detraining at Apsley I told him our destination and we walked on companionably, siblings united in absurdity. It was a perfect sunny winter’s day, and not until we were within a stone’s chuck of the BP Building which marked the southern edge of the ‘control zone’ could we smell the rankest of the rank, but the patina of profit was nowhere to be seen.

The cops at the first barricade waved us nonchalantly on after I’d engaged them in a lengthy boring about maps and logistics. At the next roundabout the roadway was heaped with the linguini of flattened hosepipe. There were emergency services vehicles a-flashing, and a cop car started tootling towards us. ‘We’ll walk towards them,’ I told my brother, ‘that way they won’t get narked.’ I flipped my NUJ card and said to the senior officer, ‘Press, we just wanted to have a look at the site.’

‘You shouldn’t be here at all,’ he replied.

‘Well, we’ll just head back the way we came,’ I said breezily.

Читать дальше