I cycled into Churchend. The weatherboard, white-painted houses were all a tad uniform and perhaps their gardens a shade too neat, but it still looked like a real village — not Midwich. It was only chatting to Fred Farenden, the landlord, in the snug of his beautiful 1659 inn that the strangeness of the place started to well over me. Fred is a rubicund and welcoming fellow, but the tale he had to tell was of enterprise constantly thwarted by indifference and bureaucratic meddling. He’d tried bird-watching weekends, B&B packages, and now he was even brewing his own beer — Beaters’ Best — but all to no avail. He still had the same sized clientele that he’d had when he first came twenty-four years before: a handful of curious trippers and yachties in the summer, then the long, quiet months of the winter.

Personally I was at a loss to understand it. It might’ve taken me thirty-five years to get to Foulness — but now I’d arrived I couldn’t conceive of any other place I’d rather be.

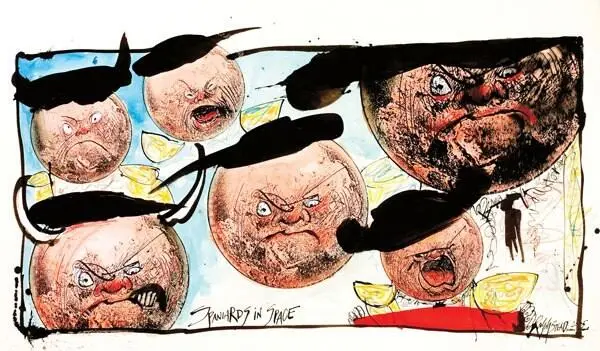

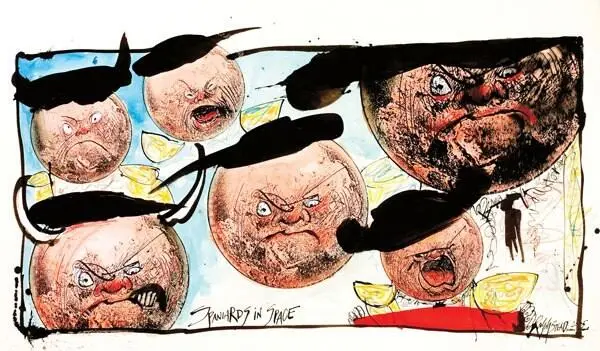

Spain — the Final Frontier

It appears that my generation — and the two or three which preceded us — were entirely wrong; far from space being the final frontier, it transpires that Spain is. Far more human effort, ingenuity and sheer dosh is being expended to send men and women to Spain than ever was putting them into space. The computing power tied up in the air traffic control mainframes, automatic pilots, baggage handling systems, on the laps of hundreds of airline passengers en route to Madrid, Barcelona and perhaps even Bilbao — completely dwarfs the dear little IBM machines which were used to crunch the numbers necessary to traject Armstrong, Aldrin and their shipmates. to the moon. I doubt you’d even be able to play Space Invaders with the pile of clunker they had at Cape Kennedy in 1969.

In the 1970s we all fondly imagined that Spain had been conquered. Been there — done that straw hat. Spain was so passé, so colonised, that there was even a Carry On film about hapless Brits pitching up on the Costa Blanca to find their hotel not yet built. Space, on the other hand, was wide open: the moon had been visited, golf had been played there, a dune buggy driven and a rigid Stars and Stripes raised. By the standards of more recent American colonial ventures this may seem pretty convincing — but we knew that there was much more infrastructure to come. First an orbiting space station where the interplanetary craft would be built, then Mars, then Venus.

Suspended animation and nuclear power were the key: knock those super-fit boffins out, tuck them in to chilly sarcophaguses, then power up the plutonium. Bosh-bosh-bosh. Why go to Spain when you could loop your spaceship round Neptune and, using the gargantuan ergs of inertia, whip like stone from a multimillion-mile-long slingshot towards Betelgeuse! Ah, the sights we were going to see, the Asteroid Belt, the Rings of Saturn (these from Ganymede, where we’d have an echoing dinner with an old buffer in a dressing gown), the Horsehead Nebula, black holes. . And because we’d be gone for so many thousands of earth years — while only ageing a few of our own — when we returned we’d find Spain entirely concreted over, and Soylent Green the only tapas available.

So entirely has that ad astra per aspera urge been sucked out of us that even to set this stuff down looks pathetic. From the standpoint of an era when Spain is the final frontier, space looks hopelessly archaic — provincial even. Can you sell time shares there? Can you look to it for a renaissance in the cinematic arts or fashion? Has space even got a cuisine to speak of? Fat chance of getting Frank Gehry to build a signature building in. . don’t make me laugh. . space. Spain, by contrast, has become everything space once promised to be, an almost infinite realm of possibility on to which human aspirations of all kinds can be projected. There is a posh Spain and a poor Spain, a gay Spain and a straight Spain, an urban, bustling Spain and a parched, deserted Spain. Some speculative thinkers have wondered whether or not Spain has any intrinsic character — such is its great diversity.

There is, however, one regard in which Spain can never hope to eclipse space, and that is as a realm of nightmarish terror and extreme privation in which an unprotected traveller can last only seconds before his lungs explode and he drowns in his own blood. True, Spain can be tough. I have spent that night in a cheap bodega in Valladolid, I have witnessed the shaming, alien beauties of Seville — and I well remember the dreadful premonition visited on me in a bank queue in Grenada in 1980. I was standing there with a fistful of traveller’s cheques when in came a doddering Brit remittance man. How could I tell this? Simple really: he wore a Burton suit contemporary with George Orwell, was carrying a BOAC flight bag full of empty wine bottles, and began to argue in pidgin Spanish with the cashier about a bank transfer from London. I thought: if I don’t get the fuck out of this country immediately I’m going to end up exactly like that, a shameful dipsomaniac paid to stay abroad by his own relatives. I went immediately to the station and hopped trains nonstop back across Europe.

It wasn’t until years later that I realised I hadn’t escaped my fate at all but rather, like Polybus, I’d run into my homicidal son on the way to Thebes. For I had become the shaky geezer arguing with the cashier — I just hadn’t had to move to Spain to do it. Then I understood what futurologists meant when they spoke of ‘innerSpain’, a realm inside the psyche within which we may travel to meet our destiny, both as a species and as individuals.

My friends Tony and Elaine have hit upon the ultimate solution to gardening — they’ve carpeted their backyard. When they moved in a couple of years ago they told me laying this fifteen-foot-square off cut was purely to stifle the great hanks of bindweed which infested the little plot, and soon they’d begin tilling with a vengeance. Recently, however, they’ve discussed recarpeting the garden on account of the stench of rotten underlay. Well, to carpet your garden once may be a weedkiller, but to carpet it twice looks suspiciously like a lifestyle.

Not that I’m critical you understand — on the contrary; with its twist pile, its set of white plastic chairs, its wonky wooden table and tattered parasol, Tony and Elaine’s garden has the virtue of making explicit what is implicit in most suburban gardens. Namely, that these are really outdoor rooms, as far removed from the grandeur of nature as Jack Straw 3is from statesmanship. Besides, they’re only part of a growing trend: modern gardens are chock-full of furniture, pergolas, loggias, decks, outdoor heaters, lamps, barbecues, Jacuzzis and giant candles. They mostly make little pretence to be anything other than roofless rumpus rooms where the lighting and temperature control are subject to cosmic vagary.

I’m not talking about serious gardens here, the kind tended by people who read books on the subject, but the family garden where dogs, kids and sunburnt drunks graze in uneasy proximity. My own awkward relationship with gardens is rooted in childhood. We lived in a high-privet-density location; the hedges were privet and such was the mania for topiary that it was often difficult to tell whether the woman in the green coat, or the green car gliding past in the road, were real or slightly shaggy simulacra, artfully shaped and then mysteriously animated. My father had little time for gardening, although he quite liked to quote Tennyson. ‘Come into the garden, Maud,’ he would declaim, and my mother would inevitably complete the couplet: ‘And mow the fucking lawn.’

Читать дальше