City breaks are quite the thing in our culture, crazed as it is with its own mad sense of alacrity. In this era of Europe’s integration its principal cities are being mashed together in the minds of its bourgeois citizens. The Rambla leads to Hradčany Castle; the Herengracht runs through the Tiergarten; and the Spanish Steps ascend the Eiffel Tower. The city break has never appealed to me that much — living in London is quite fracturing enough — but when the opportunity came up to defray travel costs to Rome against a literary reading, we decided to go. After all, what could be more surreal than a speedy sojourn in the cockpit of those ancient modernists the Romans?

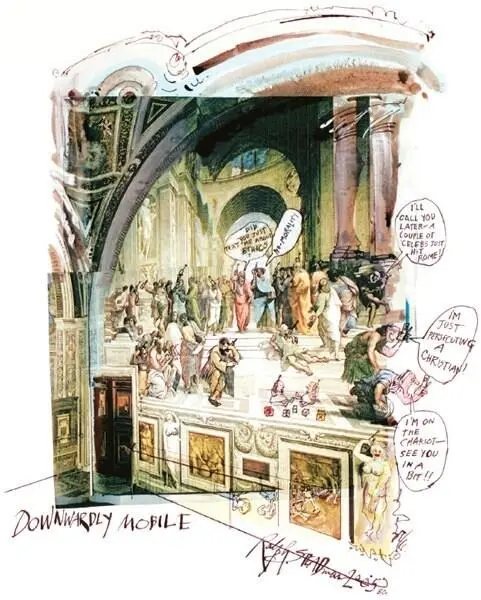

Reading Gibbon’s Decline and Fall , it always occurred to me that the reason Rome took so long in the falling — given that whole provinces regularly went AWOL — was the comparatively slow communications system. Introduce a single phone exchange, with party lines in Scythia, Dacia, Gaul and Egypt, and the Empire would’ve folded in weeks. You can only fool some of the mob for some of the time. I’d visited the city once before — for six hours to interview the pornstar-turned-politician Cicciolina — yet even this had been long enough to grasp that its sobriquet ‘Eternal’ was justified. (I mean to say, La Cicciolina herself, although Czech by birth, would be quite at home in the pages of Petronius.) A whole weekend confirmed my suspicion that Rome remains impervious to the march of time.

There was the metro to begin with. We were staying in Testaccio, the proudly nativist quartier , named after the great midden of shattered amphorae, which was the eighth hill of the ancient city (it means, literally, ‘mound of sherds’). Our local metro stop was Piramide — and is a dirty great pyramid incorporated into the Antonine wall of the city. It was difficult to believe we were entering a state-of-the-art transport hub under the austere façade of this obelisk, the tomb of an obscure second-century magistrate gripped by the Egyptology craze of his day (thus it’s basically an ancient chunk of Tudorbethan). The trains themselves were reassuringly spray-painted with graffiti, but our first stop was Circo Massimo and our second Colosseo. By the time we changed at Termini, all I could think about was that the two arms of the system — Linea A and B — insistently reminded me of the names for the ancient Minoan scripts deciphered by Michael Ventris.

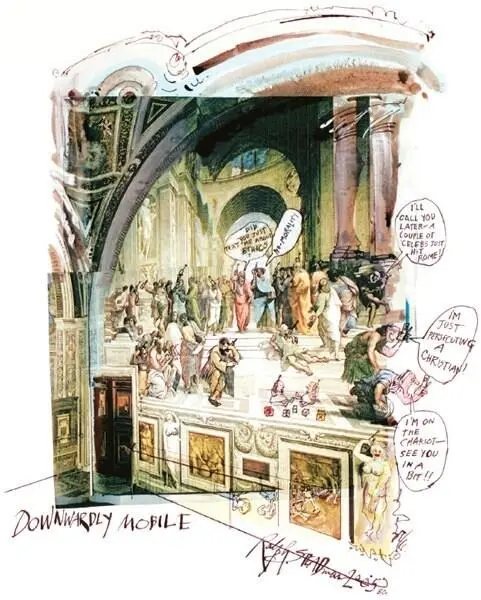

We did the obligatory round: the Colosseum, the Pantheon, St Peter’s, the Trevi Fountain, the Spanish Steps, Prada, Bulgari. That night, with the children asleep, I was lying on my bed in the failed post-modern Abitart Hotel (after all, with no modernism, the post- becomes the most proleptic of prefixes), musing on the way the view from the Capitoline Hill drenches the eye with two millennia of civilisation. In London we always think of ourselves as a two-thousand-year-old city, but the truth is that the vast bulk of the burgh is nineteenth-century red brick, bits of the Midlands reshaped and lain in orderly courses. If you want the real McCoy — all flight paths lead to Rome.

The following evening I gave my reading in a teensy theatre in Testaccio. On before me were a collective of hip young writers who called themselves ‘Babette’s Factory’. Like all Italian intellectuals they wore tweed jackets and brogues, but as a sign of their crazy modernism they also sported odd sprigs of facial hair. They took it in turns to declaim in front of a screen upon which was back-projected pulsating blobs of light. A muted jazz soundtrack accompanied them. I felt as if I were in San Francisco, in the City Lights bookstore, c . 1955. I wanted to beat my wine jug on the floor and yell, ‘Go man! Go!’

Afterwards the festival organiser explained the recherché character of the event and confirmed my thesis: ‘Basically,’ he said, ‘Italian literature hasn’t really had modernism yet. They had a little bit of Futurism and then fascism instead. The whole scene is petrified.’ Petrified, yes, but with the kind of petrification Rome offers who needs mere fluidity?

The landlord of the George & Dragon was wary; his voice dropped in tone — almost as if afraid of being overheard: ‘Oh no, no — you can’t go up there, they wouldn’t like it.’ He elaborated. ‘They’ll think you’re looking in through their windows, you might not mean to do it — but you will, and then. . well, then they’ll call Security.’ I had only suggested that I might leave the pub in Churchend and cycle up to the next village, Courtsend, but clearly this would be a mile too far. Up until that moment I’d known I was in as strange a place as you can reach in an hour by train from London — but suddenly things had turned weird.

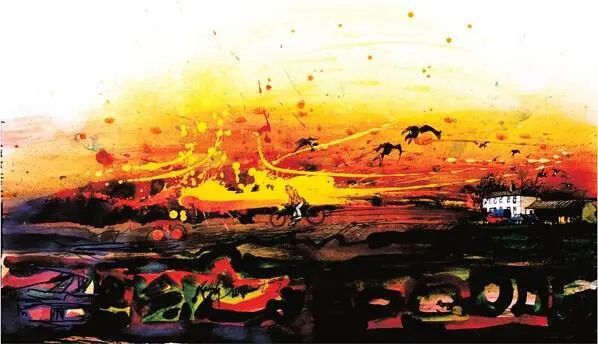

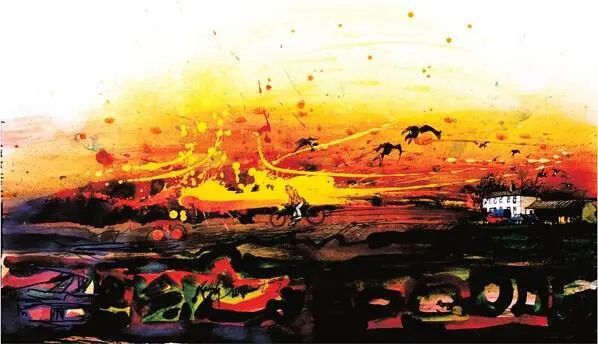

The landlord said I was allowed to cycle down to the quay, so I did. It was a half-mile or so, past the church of St Mary the Virgin, past the old primary school which had been converted into a ‘heritage centre’, past the gates to one of the strange complexes of concrete buildings which studded the green fields of the island. I cycled through a deserted farmyard; in the bare branches of the surrounding trees were huge rooks’ nests and the glossy, blue-black birds circled around me as I pedalled, relentlessly kraarking.

At the quay I sat and looked west to where the sun was setting behind a cloud, sending down a perfect fan of rays: violet, grey and pearly pink. At my feet the wide creek purled, the muddy banks were smooth and silvery. Geese clamoured overhead, while in the far distance the dwarfish tower blocks of Southend-on-Sea chewed on the horizon like the snaggle teeth of a senescent world. I felt altogether at peace in this place of war.

Foulness Island — I’d known about it for years. It was a place where sky, sea and mud merged; at once within easy reach and totally inaccessible. Over the years I’d picked up other dribs of information. I knew that the island — the largest off the Essex coast — was wholly owned by the Ministry of Defence and that there were still villages and farms on it, but it wasn’t until recently that I learned you could actually visit the place.

All you had to do, it transpired, was phone the landlord of the George and Dragon and ask him to put your name on the gate. Drinking by appointment — surely the ultimate licensing law. I pitched up late afternoon and a bored security guard signed me in. This being 2005 the MoD have passed management of the 10,000 acres of firing ranges and fields over to a private company, Qinetiqa. ‘Welcome to Foulness Island’ an electronic signboard greeted me as I pedalled off down a military road ruled straight across the flat landscape.

At first sight the island didn’t look that peculiar. I mean, not that peculiar if you’re familiar with quite how peculiar this part of the British coastline can be: to the north was Dengemarsh — of fever fame — an introverted empty quarter of dykes and isolated farmhouses. To the south, across the Thames estuary in Kent, was the Isle of Grain, where chav meets Deliverance in a duel of Burberry banjos.

I passed signs to ‘New England’ and ‘Havengore’ — both names of firing ranges. In the distance I could hear the sound of gunfire; in this bucolic context it sounded no more threatening than someone repeatedly slamming a car door. Somewhere to the south, out on the great morass of Maplin Sands, Britain’s biggest colony of avocets were wading and dipping. Isolated farmhouses stood kilometres off from the road, gaunt, austere buildings, their windows no more inviting than the cameras oddly angled over steel barriers, and fixed there — I later realised — to record the impact of artillery shells.

Читать дальше