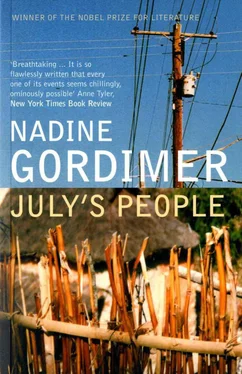

Nadine Gordimer - July's People

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - July's People» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:July's People

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

July's People: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «July's People»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, are sensitive to the plights of blacks during the apartheid state. So imagine their quandary when the blacks stage a full-scale revolution that sends the Smaleses scampering into isolation. The premise of the book is expertly crafted; it speaks much about the confusing state of affairs of South Africa and serves as the backbone for a terrific adventure.

July's People — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «July's People», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

— She said it was time. The grass was right. She wanted to cut before the other women took the best. I can’t tell your mother she mustn’t do what she wants. I am her daughter, I must help her. Perhaps you have also forgotten some things.—

— What do you mean?—

Her head on one side again, to ward off anger, but not afraid, her wheedling cringing force. — You have to learn all their things, such a long time. When you go.—

— More than fifteen years. Yes … The first time was in 1965. But I didn’t work for them, then. I worked in that hotel, washing up in the kitchen. I had no papers, that time. All of us in the kitchen had no papers, the owner let us sleep in the store-room, he locked us in so nobody could steal and take food out. — An old story, his story; her head nodded to check each point. — That was the place that burned down, afterwards, in the winter their paraffin stove started a fire there, they couldn’t get out. God was good to me.—

He had not burned to death in the white man’s city, he had brought home from that job the money to pay her father (he had already paid the cattle). She had had her first child by then, and she became his wife. That was what happened to her, her story; he came home every two years and each time, after he had gone, she gave birth to another child. Next year would have been the time again, but now he had brought his white people, he had come to her after less than two years and already she had not bled this month.

He looked at her, painfully, pityingly, as if by so doing to block out seeing something or someone else. He spoke with the rush of an enthusiasm there was not time to examine. — When the fighting’s over I’ll take you with me, I’ll take you back and show you, you’ll stay there with me. And the children too.—

Her chin thrust forward, mouth jaunty, eyes sliding to the corners of her lids, she seemed to be discovering herself in the eyes of other people. — Me, there! What would I do in those places. — Gasping and making scornful, tender clicks in her throat. — Can you see me in their yard! How would I know my road, who would tell me where to go? — She laughed and shivered bashfully. She made to take the food away but he put out his hand to show he was not finished, although he didn’t eat, again seeing something she could not know about; those Ndebele women who came in from the veld north of the city and crossed the streets bewilderedly under backward glances and giggles, their tall vase-shaped headdresses of clay-and-hair covered by striped hand-towels, old canvas football boots on their feet below cylinders of brass-wire anklets.

Laughter, the bashfulness sank slowly from the settling muscles of her face, and the baby boy, loosed from the pouch on her back, pulled at the objects that were her nose, her lips, her small black ears and the tight string of dirt-etched blue beads, prescribed by a tribal doctor, she was always armed with against misfortune. — After the fighting is over, perhaps you can stay here. You said the job was finished. If we get more lands and we grow more mealies … a tractor to plough … Daniel says we’re going to get these things. We won’t have to pay tax to the government. Daniel says. You wouldn’t have to pay the whites for a licence, you could have a shop here, sell soap and matches, sugar — you know how to do it, you’ve seen the shops in town. You understand as well as the India how to buy things and bring them from town. And now you can drive. For yourself. I see those men of our people who drive big lorries for white men. But you drive for yourself.—

The vehicle that had brought his white people had never been mentioned between the two of them. She had not remarked upon or praised his prowess while he was learning to drive it. He had said nothing; it was natural for him to assume she saw him serving his white people in this way just as he took them wood and had given them his mother’s house and the pink glass cups and saucers.

There was complicity growing in the silence. He broke it. — After the fighting … If you could have seen how it was in town. I was there. You die just like that. — There were thoughts that had to be tried out on someone. — I left my money. I couldn’t fetch it, anyway. Everything was closed up. Finished.—

In the shoulder-bag AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS his white man had passed on after the return from the architects’ congress in Buenos Aires he kept the simulated-calf wallet they had given him one Christmas. It was flattened and softened to its contents by the years he had carried it always against the contours of the body in hip or breast pocket; his passbook that his employers had to sign every month, his post office savings book, the building society savings book with its initial deposit entry of one hundred rands they had given him in recognition of ten years’ service, five years ago. The figures in his post office book rose and fell, from three figures sometimes to one. He put in five rands of Fah-Fee winnings when he was very, very lucky, he took out sums to send home when there was a crisis in his family, far from his intervention — the only authority left to him, at that distance, was money. He withdrew the savings of two years’ work, his entire capital, all he was worth to the city he was spending his life in, all that there ever was between him and a slump, unemployment, sudden disaster, old age and destitution, each time he went home on leave. He never had withdrawn anything from the United Building Society account with the hundred rands, and it had grown by itself, a rand or two a year: they explained interest to him, how money could be earned without working for it, the system whites had invented for themselves. He had never seen the money they gave him, or touched it, but it was there. They had saved him, when first he came to them, from his country ignorance, keeping his money in a cigarette tin under his mattress.

— How much? — She knew what his monthly wage was, and didn’t tell anyone else because people always ask to borrow. But she didn’t understand the source of other odd sums that came his way and sometimes were passed on to her and his mother — not always, she saw that when he used to come home on the railway bus in new clothes; this last time, two years ago, in blue jeans and matching zip-up jacket. She did not know what other money there was to be gained, or how, and on whom he spent it. The gambling game was not one that was played here at his home. A backyard, back-lanes game where the money rolled from white houses.

They had told him his money was safe, written down in those books. But now that they had run away, those books were just bits of paper. Like the other things he and his wife and his mother and all the people here kept in the dark of huts because there was so little left over from the needs of each day: the safety medal someone brought back from the mines, the Mickey Mouse watch Victor had ruined in the bath, the receipt for the bicycle paid for six hundred kilometres away.

He made a rough equivalent for her. — More than a hundred pounds. — The people here at home had never changed their calculation to the currency of rands and cents, the Indian store still marked in the old British currency the price of Primus stoves and zinc finials which, for those who could afford them, had replaced the cone of mud packed on the apex of roofs to secure the highest layer of thatch.

He thought of the pass-book itself as finished. Rid of it, he drove the yellow bakkie with nothing in his pockets. But he had not actually destroyed it. He needed someone — he didn’t yet know who — to tell him: burn it, let it swell in the river, their signatures washing away.

Chapter 18

Aman in short trousers came along the valley carrying a red box on his head. She was watching him all the way; she could no longer stay in the hut while the blond man fiddled with the radio. The children had stood obstinately before her, squinting into the sun through wild hair, when she forbade them to go swimming in the river, and she could hear their squeals as they jumped like frogs from boulder to boulder in the brown water with children who belonged here, whose bodies were immune to water-borne diseases whose names no one here knew. Maybe the three had become immune, too. They had survived in their own ability to ignore the precautions it was impossible for her to maintain for them. Victor was forgetting how to read, but did not miss his Superman and Asterix; she sat outside the hut and could not understand I Promessi Sposi. It was translated from the Italian but would not translate from the page to the kind of comprehension she was able to provide now. Only the account of bread riots in Milan in 1628 produced in her, in reflex, an olfactory impression of bread, and even that was not a craving for bread (there was none here, mealie-meal pap was bread), for the supply from the supermarket that was always ready, wrapped in plastic bags, in the freezer back there — was not a real connection made between her normal sense of self and her present circumstances, but simply the statement of the bread Lydia baked once a week. In the kitchen of the Married Quarters house on the mine, along the passage — as you opened the door, the house bloomed with the slightly fermented scent. And it was Lydia’s heavy brown bread in brick-shaped loaves. Rather tasteless; it had given all in what it breathed through the house.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «July's People»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «July's People» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «July's People» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.