G. discovered which was the best dressmaker in the city. The modiste was an old woman from Paris. He discussed with her what kind of dress Nuša should have. He said it should make her look like a queen, an empress. The modiste pointed out that Nuša was young and that to make her so regal would be to age her unnecessarily. He insisted that whatever she wore she would look young, but she must also look commanding. She must look like Sheba, he said.

Nuša submitted to the first visit for measuring like a conscript. She stood there dumb, sullen, apparently locked in the thoughts of her own life which was far away. If other village women had been undergoing the same ordeal, she would doubtless have smiled at them and whispered some truculent comment. She was not cowed but she was entirely alone in a foreigner’s world. When she caught sight of herself in one of the mirrors, she saw herself there in that salon de couture through the eyes of her mother or some of the girls at the factory and she blushed, her face and neck going a blotchy crimson, not because she was ashamed but because she could hear the story they would tell about her. She had imagined herself being married, being a mother, dying one day. But in none of the situations she had foreseen for herself was she ever as alone and central as she must be in the story they would tell about her. She knew she was justified. What she was doing or allowing to be done was not only just, it was for the sake of greater justice. But to be such a solitary and principal character was like being a criminal. She could speak to nobody about what was happening to her. It was the loneliness of her conspiracy which made her feel like a criminal. Without the slightest pretension she tried to think of Princip and Cabrinovič in their jail in Bohemia, whilst an Italian with a tape-measure called out the measurements of her back to another woman who wrote them down in a book bound in velvet.

G. arranged to see her briefly each day. They met first in the museum garden. Afterwards they went to some shop, which G. had already selected, to buy another item of her toilet. Each day Nuša carried home to her room in the street near the arsenal another parcel. As soon as she had shut the door of the room she undid the parcel and hid the contents at the bottom of the cupboard which served her as larder and wardrobe. She had already decided that after the ball she would sell everything she had acquired. And so, when on the second day she found a number of bank notes stuffed into a dancing shoe, she was not outraged. It did not appear to her as money given her by a man, but simply as part of the sum she hoped to realize when this extraordinary week was over and she must go back to the factory or find other work. She found no opportunity to steal his passport.

Most of those who served them in the shops — the jewellers, the glovemakers, the shoemakers, the haberdasher — were so astounded to see an Italian gentleman accompanied by a Slovene village girl (she was like a carthorse, they said afterwards) that they explained everything by this unusual phenomenon. But one or two may have remained more puzzled. What was the relationship between this couple? They were polite to one another but absolutely formal. They never spoke except when the outside situation demanded it. They looked at each other without rancour but equally without affection. Neither pretended to the other. There was not a trace of the theatricality that goes with prostitution. She was not a tart. Yet neither was she his wife or mistress: there was no intimacy beween them. Then why, with such care and extravagance, was he buying her these presents? Why did she give no sign of gratitude? Or, alternatively, why did she show no disappointment? At times she looked nonplussed. But most of the while she did what was required patiently and with a certain slow natural grace. Two solutions occurred to the puzzled shopkeepers. Either she was simple-minded and the Italian was in some mysterious way taking advantage of her; or else he, the Italian, was mad and she was a servant humouring him.

Nuša both hoped and dreaded that she would soon see her brother. She wanted to know what his latest plans were and she thought she might find a way of hinting that she could procure him a passport. At the same time she feared he might have heard that she was not going to the factory and would insist on her telling him what she was doing.

Bojan came to her room late on the Friday afternoon of the first week. Her fears proved unnecessary. He was so distracted by the political situation and the imminence of war that he asked her nothing about herself and assumed she was still working as before.

You must get used to eating less, he said to her abruptly, if you are a little thinner it won’t matter.

I never eat so much in the summer, she said.

The Empire will be defeated, that is certain, it cannot survive. When it topples and breaks up, all the cities will be very short of food and supplies.

When are you going to France?

I haven’t got everything I need yet. We have to make a whole organization in exile.

Will it be before next week?

I cannot tell you, but I will come to say goodbye before I go, I promise.

If you wait one week I will be able to help you. It will make it safer for you.

What do you mean?

Wait and see.

He sighed and looked out of the small window down the hill on to the docks where a cargo ship was being unloaded. The men looked as small as tin-tacks and the horses with their draycarts on the quay looked no larger than beetles.

She wanted to tell him more, not about her plan, but about her good will. Do you remember on the Sunday before last scolding me in the garden—

When I found you with that unsavoury Casanova? Yes, I remember. And, you see, that is what we fear, now more than ever, the Italians will take over the city and we shall exchange one tyranny for another. And the second tyranny will be worse than the first because between the two there will have been the lost chance of freedom. The Italians will be worse, worse even than the Austrians.

What you spoke to me about then showed me something, she said.

He continued to stare out of the window. The apparent size of the men unloading the ship intensified his pessimism. If you think, he said, of the Italy Mazzini dreamed of, if you think of Garibaldi, and you look at what Italy has become—

In Paris you will see your friend. She knew no other way to reassure him.

Yes, I will see Gacinovič. My life is like a swan flying through the fog towards a light that is very distant but irresistible. Gacinovič wrote that.

Nuša put her arm round her brother’s back and her chin on his shoulder. Their two heads close together in the small window, they looked down towards the ship whose hatches were open. Slowly, once, he rubbed his cheek against hers. It was a gesture of tenderness such as normally he would never have allowed himself, but he was overcome by an awareness of how closely their childhood had bound them together. Each of them sensed that the image of the distant light in the fog had profoundly affected the other. To neither was the light a precise symbol or hope. It was not something they could discuss together. But to measure how far away it was, both would begin measuring from the time when he first taught her to read.

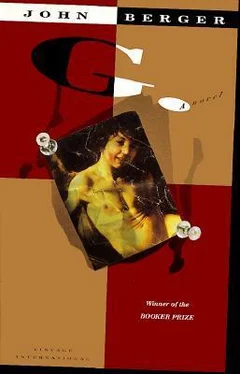

The final fitting for the dress was on the Tuesday of the second week. In three days Nuša would be paid her wage; she was still earning the passport. She gazed at the extraordinary dress she was wearing in front of the hinged mirrors.

Читать дальше