They pass a group carrying a wounded man. Others are running. Screams gush in accompaniment to the blood — but not always from the same person. Blood runs down a woman’s face, the eyes behind the blood tightly shut. An enormously fat man is half lifting her, his arm round her back. The cleared spaces enable the cavalry to charge more rapidly against those who remain. A middle-aged man alone in the middle of the Corso, fists in the air, curses the soldiers. Cowards! he shouts, Rinnegati! He advances towards a line of horsemen drawn up in stationary formation awaiting orders. An officer behind the line orders him to stop. He continues to advance. When he is shot he falls on his face.

Butterflies the colour of grey sandstone, others the colour of honeysuckle. Grass and wild flowers as high as the knee. Petals faded by the sun so that they are almost white, but not clay white like the miniature snails to be found in places on the dusty earth. Delicate wild gladioli the colour of amethysts, transparent and smaller than a finger joint. The red of poppies — the colour in which a child pictures fire. Fading poppies, damp, their fallen heads the colour of wine stains. Shallow outcrops of flat rock smooth and grey like the sides of dolphins. The whole field surrounded by ilex trees. To die in that field, blood flowing into the dry earth. To be shot, to fall across the tram lines, blood making the cobbles slippery. I picture the first death to make a wreath for the second.

She leads him across the gardens to the railyards and the streets near the station of the Piazza della Republica. She never lets go of his hand. She holds it neither amorously nor protectively but impatiently as if to make him run or walk fast, or, when they stop, as if to make him understand more immediately what they are watching. Occasionally she speaks to him in Italian although she knows that he cannot understand what she says. Shock, the strangeness of their situation and perhaps an innate desperation make her develop the fantasy which began as a joke. Soon she is pretending that one day they will get married. This pretence is no more unlikely than the events taking place round them. And so she establishes, intuitively, a balance between the violence of their circumstances and the violence of her imaginative preoccupation, and this balance enables her to become quite calm.

They watch a tram being overturned to make a barricade. As it falls the glass of all its windows is smashed. Having unharnessed the horse, men and women drag a carriage to overturn beside the tram. A line of railwaymen are carrying picks and crowbars from a railway depot. The news has spread that the army has been ordered to clear the city, street by street, and to hunt down every ‘insurgent’. Another group of railwaymen are dismantling the track.

Everything is about to be transformed.

Imagine the blade of a giant guillotine as long as the diameter of the city. Imagine the blade descending and cutting a section through everything that is there — walls, railway lines, wagons, workshops, churches, crates of fruit, trees, sky, cobblestones. Such a blade has fallen a few yards in front of the face of everyone who is determined to fight. Each finds himself a few yards from the precipitous edge of an infinitely deep fissure which only he can see. The fissure, like a deep cut into the flesh, is unmistakably itself; there can be no doubting what has happened. But there is no pain at first.

The pain is the thought of one’s own death probably being very near. It occurs to the men and women building the barricades that what they are handling, and what they are thinking, are probably being handled and thought by them for the last time. As they build the defences, the pain increases.

A man from the rooftops shouts that there are hundreds of soldiers at the corner of the Via Manin.

Umberto and four of the hotel staff whom he has specially paid and to whom he has offered a further reward of a hundred lire if they find his son, are searching in the streets behind the hotel where there are neither soldiers nor barricades.

At first, says the Roman girl in Italian, we’ll live in Rome because I think we’ll be happier there.

Whenever she speaks, he looks at her in the same way as he would if he understood her. The meaning of her words seems unimportant to him; what is important is that what he is seeing, he is seeing in her presence.

And you will buy me, she says in Italian, some white stockings and a hat with chiffon tied round it.

At the barricades the pain is over. The transformation is complete. It is completed by a shout from the rooftops that the soldiers are advancing. Suddenly there is nothing to regret. The barricades are between their defenders and the violence done to them throughout their lives. There is nothing to regret because it is the quintessence of their past which is now advancing against them. On their side of the barricades it is already the future.

Every ruling minority needs to numb and, if possible, to kill the time-sense of those whom it exploits by proposing a continuous present. This is the authoritarian secret of all methods of imprisonment. The barricades break that present.

The Roman girl leads him into a doorway a few yards from a barricade. We will wait here a little, she says in Italian, like a wife to an elderly husband on the occasion of a cloudburst.

The soldiers draw nearer. The last doubt that the action may be deferred disappears. Kneeling at one end of the barricade with his back against a basement grille is a white-haired man with an old pistol across his knee. It is loaded; he has one other bullet in his pocket. Younger men and women are still dismantling the road and adding to the pile of cobbles. Others are armed with bars and sticks.

Everyone falls silent. There is a distant noise of hammering from the yards and, nearer, regular as the sound of a clock (its promise of a seemingly endless time lulls him; but the way it fills the time, whose passing it records, oppresses him) the noise of marching feet. La Rivoluzione o la morte! shouts the white-haired man into the silence. And then: Sing, damn them, sing! They must hear us singing.

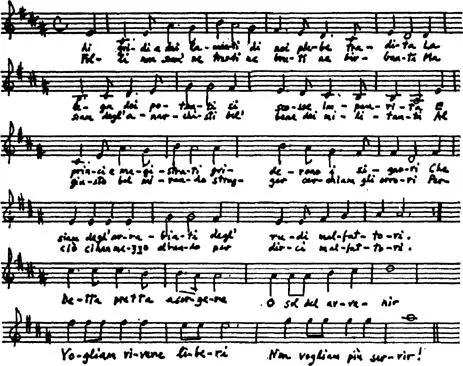

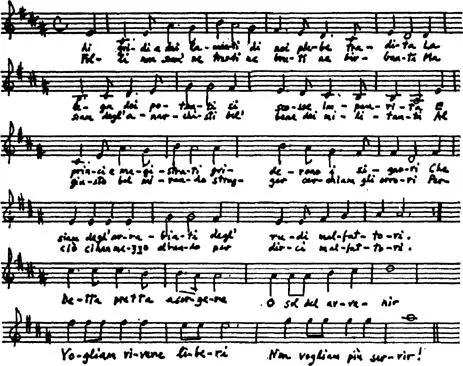

When he first commanded Sing! the Roman girl went forward to the step of the doorway, simply, as to the footlights, and began to sing the ‘Canto dei Malfattori’ .

It is hard not to romanticize her voice. At first I thought it frail like her arms which so impressed him. But it is full and coarse. For a moment nobody in the street joins in, the better to appreciate how her voice fills the street and seems instantaneously to soften every surface and edge.

The soldiers fire their first volley into the barricade.

The first volley simplifies, its echo killing every distraction. Nothing remains but what is in hand. A few men throw stones towards the soldiers; they fall short. A shutter bangs and an officer fires with his revolver at the window of the house. On the road between the soldiers and the barricade, absolutely still, are the seven stones that have fallen short.

Behind the barricade women get down on their knees to gather stones along the perimeters of the holes already made and to feed them to the men. A railwayman, still wearing his cap with a red and gold braid round it, shouts: Wait! Wait till we can break their heads in! Wait! And when I say — all of us at once! Wait! He has a bony, quick face and he is smiling.

The soldiers close up. A second volley. For the second time nobody is hurt. Nobody believes it, yet nobody fails to consider that the justice of their cause may be a protection. Now! Twenty men hurl their stones through the air. The soldiers edge back. A woman jeers at them: Faccie di merda!

Читать дальше