“Painting? Authenticate?” I asked.

“He’ll have to tell you about it. It’s his trip,” she told me. Then she said, “Hang on a minute,” and there was a rustling sound — my mother’s open hand closing over the telephone’s mouthpiece — and I could hear her saying to S., in a stage whisper that revealed the faint nasality of her southern-Appalachian accent, “Go ahead and tell Don what you need to tell him. He’ll listen.”

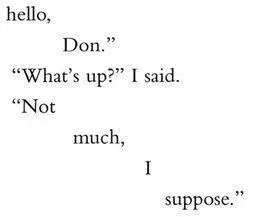

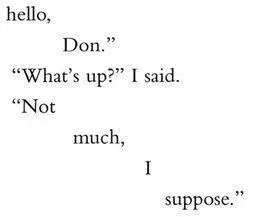

S. spoke exceedingly slowly and quietly. I stood in the cramped and cluttered kitchen of the Upper East Side apartment that I shared, in those days, with my girlfriend, K. I pressed the phone receiver against my ear and heard S.’s soft, anxious voice, a voice made, as I think of it now, almost entirely of breath, of exhalations, saying, at the excruciating rate of about one word every ten seconds — I am exaggerating in fact, though not in spirit—“Oh,

“Mom says you’re coming to New York,” I said quickly, trying to use my own words the way an English bobby uses his nightstick to hurry vagrants along.

“New York …,” he said.

And I waited.

“ … Yes …,” he went on.

We waited. And eventually, gradually, infuriatingly, in bits and pieces, a story emerged — the story of the painting.

The painting, I learned, was old. It was rectangular in shape, maybe four feet tall and two feet wide. Its wooden frame was large and slightly ornate. As I understood things, the work belonged — or had once belonged — to a man who owned a brownstone in Chelsea, a boardinghouse, a building in which men lived in rooms. It is possible that this man had bought the painting somewhere in Europe or America. Or maybe he had simply found it.

Slowly, over the course of many minutes, my mother’s boyfriend in Miami told me that there had been another man on the scene in the downtown boardinghouse. For some reason, I am under the impression that this man was related to a friend of S.’s; he was, I believe, one of several cousins who at one time or another either had possession of or claimed to know something about the painting. Anyway this man remembered having seen, in an art magazine, a reproduction of the work. The cousin could not recall the name or the date of the magazine or even the content of the article. In fact, all the cousin remembered with any certainty, according to S., was the fact that the painting was “important.”

But in what way important? This was the question that was to become— had become — S.’s obsession.

For nearly fifteen years after he left New York, my mother told me, S. had wandered up and down the Eastern Seaboard, living in short-term lodgings, drinking, and working the kinds of temporary jobs — auto-body painting, sign painting, construction, and so on — that are often performed by people in his situation. At a certain point, he wound up back in Florida, where he was from, and where, after repeated attempts — in this he was like my mother; the movement from defeat to recovery was a bond between them — he had managed to get, and stay, sober. He had even begun, for the first time since dropping out of the School of Visual Arts in New York, to paint.

I have one of S.’s paintings from this period hanging on my living-room wall. Like all the works he made after joining AA and moving into my mother’s condominium in South Miami, it is signed with his middle name, Craig. It is small, more or less the size and shape of an LP record jacket, and it is, as were many of S.’s works, a landscape. But it is not painted from life. Or is it? It shows, in the middle distance, and to the right side, a steep-sided mountain, predominantly white and lavender in color, as if overgrown with flowering plants. In the upper-left foreground (hanging down from a corner, like decorative proscenium elements) are some delicately painted leaves that look almost prehistoric; far off to the right, against the mountain and a blue-white-lavender sky, a solitary, impossibly tall and narrow palm tree seems to be growing out of an impossibly deep and wide gorge. When I look at the painting, with its strange topography, its sliver of moon in an unnatural sky, and its dizzying, off-center palm tree, I feel there is something amiss in the relative sizes and positions of the objects. The effect is of a disturbance, either in the mind of the painter or in the world of the painting. And I feel, considering this disturbance, that the scene is missing something — a Tyrannosaurus rex , perhaps. Then I notice, in a way that has more to do with feeling than observation, the symmetry inside the disturbance, and I am aware that S., deliberately and skillfully, or maybe by accident, has painted a truly alternative world, which is to say a world that is different from ours not only by virtue of the imaginary elements of which it is composed but also in the laws of whatever nature governs the spatial relations between those elements.

But what about the other painting, the one from S.’s days as a young artist living in New York? For S., that painting had been, during his transient years, a source of creative contemplation, and a symbol of whatever remained in him of the will to escape his circumstances and work as an artist. More to the point — and especially during the period when he was, to use an expression that is popular in AA rooms everywhere, hitting bottom — it had, I believe, served as a symbol, maybe the spiritual symbol, of his desire to live. He had thought about, and pondered over, that painting almost every day of his life as an alcoholic. When he was spraying paint on rusted cars, when he was hammering carpentry nails, when he was sitting at a bar, in New York or Florida, he thought about the painting. S. thought about the man who had first suggested the importance of the work, and about the magazine article that he had heard about but never seen; and these thoughts led him to think about European and American painting traditions, and about the history of art in general, and, I suppose, about all the famous paintings that he had seen only in books. The memory of the important painting in its huge and heavy wooden frame — not to mention a preoccupation with the thought of one day verifying his evolving ideas about the painting’s provenance — had, I realized in my conversations with both S. and my mother, helped keep him alive.

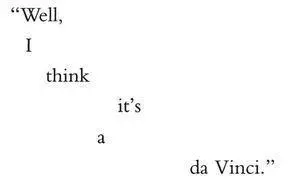

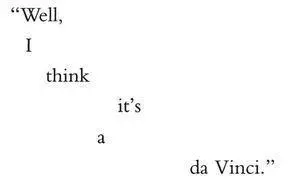

“What do you think it is?” I finally asked him at some point in our phone conversation, that day in 1988.

“A what?” I said.

“ … a Leonardo da Vinci,” he said.

“Put Mom on the phone, okay?” I said.

“Hello? Don?”

“What’s going on?”

“He believes the painting may be a Leonardo da Vinci, dear.”

“I know. I heard him.”

“He’s going to spend a week in New York and he wants to research this and he wants to know if you’ll help.”

“Help?”

Which is what I did. After a fashion. When you are, as I was — and as I am — the anxious child of a volatile, childlike mother, you learn how to appear to accept, as realistic and viable, statements and opinions that are clearly ludicrous.

You may learn, too, as a defense against the absurd disappointments caused by fragile and unhappy parents, the crude art of sarcasm. “When is he coming on this vision quest?” I asked my mother, and she filled me in on the details. A month or so later, S. took up temporary lodging with — and here the story becomes somewhat foggy — one or another of those above-mentioned cousins, the man who, following the death of the owner of the downtown boardinghouse in which S. had first seen the painting, now had possession of the painting. S. promptly photographed it, then took a pair of scissors and cut swatches from the spare canvas tucked away along the inside perimeter of the stretcher. This seemed to me to be an act of mutilation, or, at the very least, one of proprietary aggression, and probably out of keeping with whatever protocol might exist for the care of old artworks. Were you supposed to chop up the canvas? On the other hand, what concern was it of mine? Why should I care what S. might do to some painting that was, in all likelihood, just a piece of junk sitting in an apartment?

Читать дальше