Nadine Gordimer - The Conservationist

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - The Conservationist» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1983, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

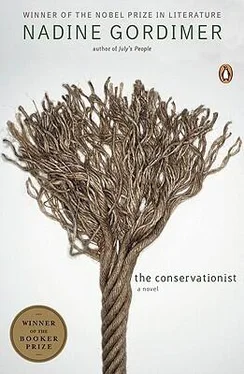

- Название:The Conservationist

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1983

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Conservationist: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Conservationist»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Conservationist — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Conservationist», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In the bus queues at the location gates people stood under more sheets of plastic, scavenged from the packing in which the factories near by received materials. The distended buses lurched cautiously round from the gates to the road, their windows steamed-up inside and streaming outside. Location taxis, old and huge, were the first to be stranded by water on the plugs or in the distributor. But soon there were cars from the city, as well, with grimacing white men in raincoats dirtying their handkerchiefs in an attempt to dry off some vital part of the engine, or waiting anxiously for a passing black, bent drenched over a bicycle, to stop and help push the car out of the way of traffic. The traffic moved slower and slower; came to a stop. Sometimes there had been an accident, someone had skidded and caused a collision, and helplessly, clumsy in a chain-mail of rain, a string of cars collided nose-to-tail behind the first, as the coaches of a shunting train buffet each other. Once it was a transport vehicle blocking the way, a huge tented thing from the abattoir. Water streamed over marbled pink statuary of pig-carcases; the attendant workers in their yellow sou‘westers clambered about, black seamen trying to batten down canvas against high seas. The sense of perspective was changed as out on an ocean where, by the very qualification of their designation, no landmarks are recognizable. The familiar shapes of factories lined the road somewhere, if they could have been seen and if what the tyres went over as if greased, engaging with a tangible surface only on intermittent revolutions, was a road somewhere. At the three-way intersection a sheet of water formed through which most vehicles could venture successfully the first few days so long as more rain was not falling too heavily at the time, making visibility nil. When there were children in these cars they shrieked with pleasure and fear at the lack of sensation — the impression of being carried along without any kind of familiar motion; it seemed arms that bore them let go, yet they did not fall. Red of their lips and tongues and bone and blubber-white of their noses pressed gleefully against the windows made melting, distorted images loom up to the cars behind: flesh disintegrated by water. On the Friday the sky held for a few hours and there was a tender area of glare where the sun must have been buried, a grey pearl in jewellers’ cottonwool or an opaque insect-egg swathed in web, and in the lunch-break white youths from the Fiat assembly plant rolled the legs of their jeans and waded, goading one another in Afrikaans. By four o’clock, when the factories were closing for the week, rain so close and heavy it actually pummelled the flesh of the black backs on bicycles, came from over the Katbosrand hills. The artificial lake might be only a few inches deep in places; it might be over the axles of cars in others. Everywhere the dim-lit submarine habitations waited. A young man stripped to his underpants emerged from one as if daring a line of tracer bullets, arms over his head, knees comically bent, kicking up water in water, against water, and bolted back again. Some vehicles were slowly reversed, eddying round their own axes, and crawled off up the roads again. One — in a great hurry perhaps, or merely bored and impatient — began to edge round the lake. The car wavered, tipped, obviously floated, then found solidity again, and from the lalique glimmer of its lights, could be judged to have regained safely the slight rise on the far side of the hazard. Another crept out and the people closed in the car nearest it heard the determined change to second gear. But this time, just as it had come through what must have been the deepest water, because there, too, like the first car, it was seen to float a moment and then engage with some solid surface again — just as it was about to gain the rise, something burst, out there: one of the many tributary streams that fed the vlei from miles away, unseen, swollen unbearably for six days, ruptured like a blood-vessel and shot mud-red into the lake, the final violent, infinitely distant whip of the cyclone’s passing, the final fulfilment of the weather outlook for the Moçambique Channel. The car swung sideways, tilted, and was sped over the drop to a gulley below the right of the road, now a waterfall and in moments a tangled heaving river, bearing away, bearing away. It made its escape tearing through the eucalyptus between the cyanide mountains, frothing a yellow saliva of streaming sand. A man got out of one of the stationary cars and staggered a few yards, arms out, in the direction that the car had disappeared. He clearly had difficulty in keeping on his feet. He staggered back again, arms stretched in the direction of shelter.

Safety, solid ground.

That little gully: who would have thought it. Mehring read about these things with the intense, proprietorial excitation with which one learns that a murder has taken place only two doors away from a house one has lived in for years — in an ordinary house on whose mat the newspaper has been seen lying each evening, a house from whose gate the same dog has barked the countless times one has passed by. That little gully. There ought always to have been a paling there — a drunk might have gone over some night, swerving too quickly. But who could ever have imagined that the trickle of water that sometimes dried up altogether for months on end so that that gully was nothing more than a culvert full of khaki-weed and beer cartons thrown in by the blacks, the trickle of water that in normally rainy weather was never more than a gout from the big round concrete pipe that contained it under the road, could become a force to carry away a car and its occupants. ‘Without a trace’, the reports said, ‘before the horrified eyes of astonished witnesses’; the search went on for three days during which hundreds of people drove as near as they could to the washed-away road and walked the rest, scrambling along behind the police who were dredging the water. These fans and afficionados of an unnamed sport were so enthusiastic a following that more police were deployed to keep them back; finally the area had to be declared closed to the public. In addition to a nine-year-old wedding picture of the missing couple, a Mr and Mrs Loftus Coetzee, supplied by their relatives, there were pictures of the disappointed crowd with their children and umbrellas. Mr and Mrs Loftus Coetzee were found drowned in the car from which they had been unable to get out, deep in the new river that had made its bed for them; the reason why their car had been so difficult to find was that the water had carried them to, and flooded, one of those wide pits between the disused mine dumps that had long been a graveyard for wrecked cars and other obstinate imperishable objects that will rust, break and buckle, but cannot be received back into the earth and organically transformed.

Although he had every reason to visit the scene — he was cut off from his farm by the washaway, after all, it was greatly to his interest that repairs to the road should be begun at once — he kept away until that business was over. The telephone wires on the farm itself must have been down; the exchange said they could get through to other farms on the party line but his place couldn’t be raised. He phoned old De Beer and got Hansie, who said the only other road — the long way round, 60 kilometres by way of Katbosrand Station — didn’t make sense because the vlei had risen so much the approach was impassable from that side, too. But Hansie thought everything was all right on Mehring’s place; one of the boys from there had got across at some point and reported that apparently no stock had been lost. De Beer had forbidden his boys to attempt any crossing since then because one of the women had been fool enough to try and she was drowned — washed up right away down at Nienaber’s.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Conservationist»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Conservationist» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Conservationist» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.