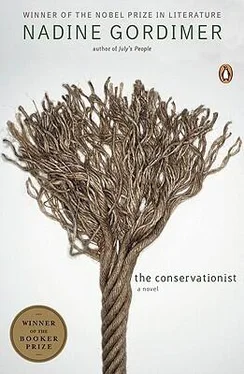

Nadine Gordimer - The Conservationist

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - The Conservationist» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1983, Издательство: Penguin Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Conservationist

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1983

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Conservationist: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Conservationist»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Conservationist — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Conservationist», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jacobus considers a moment. — Is too much water. Too much. - He goes through the motions of pitching a spade, lifting earth, and then standing back, the imaginary spade has dropped, he is dismayed: — As soon you digging, the water’s coming again. Even in that camp up there, not so near the river, when I’m start dig, is filling up. —

— No, no, that doesn’t matter. That’s nothing. If you find the proper place, the proper slope, after a day that big water will have flowed away. Then slowly every day the earth will drain, it’ll dry — come I’ll show you where -

The third pasture, for instance, is half-emerged from water already; he can even make out, from where he has had to stop because he hasn’t gumboots on (he thought there was a pair at the house but they’ve disappeared) the tops of the stones that mark the place where a sheep was roasted. He can’t go any farther than this but Jacobus is instructed to go down all the way along the vlei and find out how deep or shallow this ground-water is. It’s ridiculous, just leaving land to turn back to swamp; water can’t be more than a few inches in most places, by now. Jacobus says nothing; which means he’s not too keen, doesn’t want to slosh around in the muck, no doubt he’s had enough of it, but that’s too bad. The place must be got going again. For everything in nature there is the right antidote, the action that answers. Even fire is not — was not — irreparable, organically speaking. Look how everything came back. How the willows must be laved by all that water, now! How brilliant, beetle’s-wing-green their leaves are… that ash, partly their own destroyed substance, must have fed them, in the end. Nature knows how to use everything; neither rejects nor wastes.

Down there Jacobus is taking giant’s steps. He wades and plods; he is too far away for his pauses and pressings-on to be interpreted. It’s not possible to walk much, wearing ordinary boots. All one can do, up here, is stride carefully from hummock to hummock, avoiding water as children avoid stepping on the lines of paving. He gives up; he’s simply standing now, and for the first time since he arrived, for the first time since the flood, he is exposed to the place, alone: it comes to him not as the series of anecdotes and imagined images it was while he was being told how it looked and what happened there in the past two weeks, but in its living presence.

A bad smell. A smell of rot.

No, not bad: ancient damp, vegetal dank, the fungoid smell of the pages of old books, the bitter smell of mud, the green reek of a vase where the stems of dead flowers have turned slimy. Twice in the short distance he has managed to cover he has seen a clot, a black coagulation aborted out of the mud. Prodding with a stick shows these to be nothing but drowned rats.

His gaze is the slow one of a lighthouse beam. Something heavy has dragged itself over the whole place, flattening and swirling everything. Hanks of grass, hanks of leaves and dead tree-limbs, hanks of slime, of sand, and always hanks of mud, have been currented this way and that by an extraordinary force that has rearranged a landscape as a petrified wake.

A stink to high heaven.

Yes, it does smell bad. The sun is a yeast. The whole place is a fermenting brew of rot, and must be; that’s life, that deathly stink. As there were the foetuses of hippos there’s a lump of dead rat. (Alas, young guinea fowl chicks will have gone the same way.) He feels an urge to clean up, nevertheless, although this stuff is organic; to go round collecting, as he does bits of paper or the plastic bottles they leave lying about. He has been so busy tidily looking he hasn’t noticed Jacobus has turned back and is coming straight up the third pasture through the shallow pools and mud and is almost upon him again.

Jacobus is in a hurry. He’s running, so far as this can describe the gait possible in such conditions, over such terrain, stumbling and sliding, lurching, slipping. There’s the sensation that the eyes of the old devil are already fixed on him before they can be seen, before the face can be made out. When it is near enough to separate into features he becomes strongly and impressively aware that there is something familiar, something that has already happened, something he knows, in their expression.

Jacobus is panting. His nose runs with effort and a clear drip trembles at the junction of the two distended nostrils.

Jacobus is going to say, Jacobus is saying — Come. Come and look. —

‘And who was Unsondo?’ — ‘He was he who came out first at the breaking off of all things (ekudabukeni kwezinto zonke).’ — ‘Explain what you mean by ekudabukeni.’ — ‘When this earth and all things broke off from Uthlanga.’ — ‘What is Uthlanga?’ — ‘He who begat Unsondo.’ — ‘Where is he now?’ — ‘O, he exists no longer. As my grandfather no longer exists, he too no longer exists: he died. When he died, there arose others, who were called by other names. Uthlanga begat Unsondo: Unsondo begat the ancestors; the ancestors begat the great grandfathers; the great grandfathers begat the grandfathers; and the grandfathers begat our fathers; and our fathers begat us.’ — ‘Are there any who are called Uthlanga now?’ — ‘Yes.’ — ‘Are you married?’ — ‘Yes.’ — ‘And have children?’ — ‘Yêbo. U mina e ngi uthlanga.’ (Yes. It is I myself who am an uthlanga.)

No, no.

No, no. The struts of the Indians’ water-tank are broken on one side, the rain’s done it, undermined the thing, it’s about to collapse. No no. The place was bought for relaxation. We lay there shut up in the house on summer afternoons while you said you were having your hair done; I parted your legs while you were in the bath and soaped you with my own hands because, as you once so graciously admitted, I’m not without tenderness, no ordinary etc., etc. Tank’s going to fall unless they do something about it, they won’t, peace will end up face-down in the mud. Peace hurtles along on a thousand motorbikes, is worn on the sleeves of leather jackets that pocket flick-knives, and is drawn in red ink on a satchel containing books on unnatural violation of the male body, or plain buggery, that’s the real name of what you’re curious to know more about. No, no, no. What’s the point? What can be left, after ten months? If those boere bastards had done what they should, it would never have been there. They couldn’t even see to it that a proper hole was made. Scratch the ground and kick back a bit of earth over the thing like a cat covering its business.

But no. No, no. It was dumped there in the first place, not taken away, in the second, and is certainly not the responsibility of the owner of the property. A dead trespasser nobody claims. Why should anyone? No. no. There are a hundred-and-fifty thousand of them in those houses passing on the right, rolled out by speed behind the high fence under the smoke. The women in the bus queues at the gates are busy with a flash of implements and crude coloured yarn while they stand. They’re tough. Sheets of broken water around their feet; and the passing car flings it in their faces. They’re used to anything, they survive, swallowing dust, walking in droves through rain, and blown, in August, like newspapers to the shelter of any wall.

Recognized by the shoes and apparently what’s left of a face, with the — that’s enough! Why hear any more, it’s not going to do anybody any good. That’s enough. A hundred-and-fifty thousand of them practically on the doorstep. It was something that should have been taken into consideration from the beginning, before the deed of sale was signed. They’ll plough down palaces and thrones and towers, you said, smiling defiantly, in the ring of voice that I know means you’re quoting some poem; you waited to see if I would recognize the lines, knowing damn well we pig-iron ‘millionaires’ don’t read poetry, and that makes you feel superior, particularly if it’s one of your left-wing geniuses no one’s ever heard of. And you laugh: — Roy Campbell, South African fascist. — No ordinary S.A. fascist, I’m sure — I’ve amused you, again. It disposes you well to me; as I walk about the room in the house that is exciting because we know that from outside it looks as if there’s nobody in it, I feel your gaze on my penis that’s thrust out a stiff yearning tongue, helpless, even though I’m moving casually enough around fetching a cigarette or pouring a drink to bring to the bed. Others have examined the thing, of course, as you are doing. Some woman once said that the tip or head looked just like a German helmet; that dates me: it must have been during the war — I was only sixteen when it began. What can be left that is recognizable after so long in the earth. The vlei never dries out. It is always wet, down there, moist anyway. There are worms in that ooze. Spaghetti with bulges of pink; not spaghetti, more like those tubes that are part of the innards of a chicken — the solid white line on the road is preventing him from overtaking a frozen chicken delivery van ahead. Rats, and water-rats. There are no jackal. They are nature’s scavengers. They keep the veld clean. De Beer has not seen a jackal for more than ten years. - Oh no. A helmet! It’s exactly like the middle of a banana flower. Even the purplish colour and the slight moist shine. You know how the banana flower hangs sideways from the plant? —

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Conservationist»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Conservationist» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Conservationist» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.