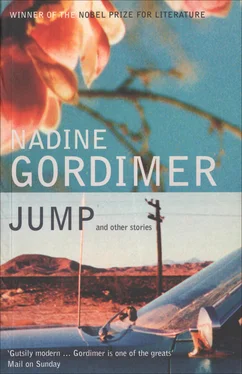

Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Jump and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Paperbacks

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Jump and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Jump and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a vivid, disturbing and rewarding portrait of life in South Africa under apartheid.

Jump and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Jump and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

All present work for Van der Vyver or are the families of those who work; and in the weeding and harvest seasons, the women and children work for him, too, carried — wrapped in their blankets, on a truck, singing — at sunrise to the fields. The dead man’s mother is a woman who can’t be more than in her late thirties (they start bearing children at puberty) but she is heavily mature in a black dress between her own parents, who were already working for old Van der Vyver when Marais, like their daughter, was a child. The parents hold her as if she were a prisoner or a crazy woman to be restrained. But she says nothing, does nothing. She does not look up; she does not look at Van der Vyver, whose gun went off in the truck, she stares at the grave. Nothing will make her look up; there need be no fear that she will look up; at him. His wife, Alida, is beside him. To show the proper respect, as for any white funeral, she is wearing the navy-blue-and-cream hat she wears to church this summer. She is always supportive, although he doesn’t seem to notice it; this coldness and reserve — his mother says he didn’t mix well as a child — she accepts for herself but regrets that it has prevented him from being nominated, as he should be, to stand as the Party’s parliamentary candidate for the district. He does not let her clothing, or that of anyone else gathered closely, make contact with him. He, too, stares at the grave. The dead man’s mother and he stare at the grave in communication like that between the black man outside and the white man inside the cab the moment before the gun went off.

The moment before the gun went off was a moment of high excitement shared through the roof of the cab, as the bullet was to pass, between the young black man outside and the white farmer inside the vehicle. There were such moments, without explanation, between them, although often around the farm the farmer would pass the young man without returning a greeting, as if he did not recognize him. When the bullet went off what Van der Vyver saw was the kudu stumble in fright at the report and gallop away. Then he heard the thud behind him, and past the window saw the young man fall out of the vehicle. He was sure he had leapt up and toppled — in fright, like the buck. The farmer was almost laughing with relief, ready to tease, as he opened his door, it did not seem possible that a bullet passing through the roof could have done harm.

The young man did not laugh with him at his own fright. The farmer carried him in his arms, to the truck. He was sure, sure he could not be dead. But the young black man’s blood was all over the farmer’s clothes, soaking against his flesh as he drove.

How will they ever know, when they file newspaper clippings, evidence, proof, when they look at the photographs and see his face — guilty! guilty! they are right! — how will they know, when the police stations burn with all the evidence of what has happened now, and what the law made a crime in the past. How could they know that they do not know. Anything. The young black callously shot through the negligence of the white man was not the farmer’s boy; he was his son.

Home

Lighted windows: cutouts of home in the night. When he came from his meeting he turned the key but the door was quickly opened from the inside — she was there, Teresa, a terribly vivid face. Her thin bare feet clutched the floorboards, she was in her cotton nightgown that in bed he would draw away tenderly, the curtain of her body.

— They’ve taken my mother. Robbie and Francie and my mother.—

He must have said something — No! Good God! — but was at once in awe of her, of what had happened to her while he was not there. The questions were a tumble of rock upon them: When? Where? Who told her?

— Jimmy just phoned from a call box. He didn’t have enough change, we were cut off, I nearly went crazy, I didn’t know what number to call back. Then he phoned again. They came to the house and took my mother and Francie as well as Robbie.—

— Your mother! I can’t believe it! How could they take that old woman? She doesn’t even know what politics is — what could they possibly detain her for?—

His wife stood there in the entrance, barring his and her way into their home. — I don’t know… she’s the mother. Robbie and Francie were with her in the house.—

— Well, Francie still lives with her, doesn’t she. But why was Robert there?—

— Who knows. Maybe he just went home.—

In the night, in trouble, the kitchen seems the room to go to; the bedroom is too happy and intimate a place and the living-room with its books and big shared desk and pictures and the flowers he buys for her every week from the same Indian street vendor is too evident of the life the couple have made for themselves, apart.

He puts on the kettle for herb tea. She can’t sit, although he does, to encourage her. She keeps pulling at the lobes of her ears in travesty of the endearing gesture with which she will feel for the safety of the ear-rings he has given her. — They came at four o’clock yesterday morning.—

— And you only get told tonight?—

— Nils, how was Jimmy to know? It was only when the neighbours found someone who knew where he works that he got a message. He’s been running around all day trying to find where they’re being held. And every time he goes near a police station he’s afraid they’ll take him in, as well. That brother of mine isn’t exactly the bravest man you could meet…—

— Poor devil. D’you blame him. If they can take your mother — then anybody in the family—

Her nose and those earlobes go red as if with anger, but it is her way of fiercely weeping. She strokes harder and harder the narrow-brained head of the Afghan hound, her Dudu. She had never been allowed a dog in her mother’s house; her mother said they were unclean. — It’s so cold in that town in winter. What will my mother have to sleep on tonight in a cell.—

He gets up to take her to his arms; the kettle screams and screams, as if for her.

In bed in the dark, Teresa talked, cried, secure in the Afghan’s warmth along one side of her, and her lover-husband’s on the other. She did not have to tell him she cried because she was warm and her mother cold. She could not sleep — they could not sleep — because her mother, who had stifled her with thick clothing, suffocating servility, smothering religion, was cold. One of the reasons why she loved him — not the reason why she married him — was to rid herself of her mother. To love him, someone from the other side of the world, a world unknown to her mother, was to embrace snow and ice, unknown to her mother. He freed her of the family, fetid sun.

For him, she was the being who melted the hard cold edges of existence, the long black nights that blotted out half the days of childhood, the sheer of ice whose austerity was repeated, by some mimesis of environment, in the cut of his jaw. She came to him out of the houseful, streetful, of people as crowded together as the blood of different races mixed in their arteries. He came to her out of the silent rooms of an only child, with an engraving of Linnaeus, his countryman, in lamplight; and out of the scientist’s solitary journeys in a glass bell among fish on the sea-bed — he himself had grown up to be an ichthyologist not a botanist. They had the desire for each other of a couple who would always be strangers. They had the special closeness of a couple who belonged to nobody else.

And that night she relived, relating to him, the meekness of her mother, the subservience to an unfeeling, angry man (the father, now dead), the acceptance of the ghetto place the law allotted to the mother and her children, the attempts even to genteel it with lace curtains and sprayed room-fresheners — all that had disgusted Teresa and now filled her with anguish because — How will a woman like my mother stand up to prison? What will they be able to do to her?—

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Jump and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.