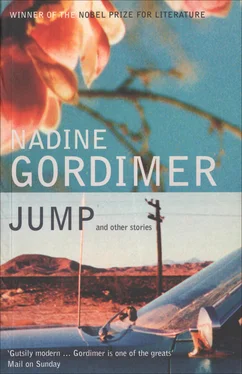

Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Jump and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Paperbacks

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Jump and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Jump and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a vivid, disturbing and rewarding portrait of life in South Africa under apartheid.

Jump and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Jump and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

They are stacking their plates and cups, not knowing what they are expected to do with them in this room which is a room where apparently people only eat, do not cook, do not sleep. While they finish the bananas and apples (Shadrack Nsutsha had seen the single peach and quickly got there first) she talks to the spokesman, whose name she has asked for: Dumile. — Are you still at school, Dumile? — Of course he is not at school— they are not at school; youngsters their age have not been at school for several years, they are the children growing into young men and women for whom school is a battleground, a place of boycotts and demonstrations, the literacy of political rhetoric, the education of revolt against having to live the life their parents live. They have pompous titles of responsibility beyond childhood: he is chairman of his branch of the Youth Congress, he was expelled two years ago — for leading a boycott? Throwing stones at the police? Maybe burning the school down? He calls it all — quietly, abstractly, doesn’t know many ordinary, concrete words but knows these euphemisms—‘political activity’. No school for two years? No. — So what have you been able to do with yourself, all that time?—

She isn’t giving him a chance to eat his apple. He swallows a large bite, shaking his head on its thin, little-boy neck. — I was inside. Detained from this June for six months.—

She looks round the others. — And you?—

Shadrack seems to nod slightly. The other two look at her. She should know, she should have known, it’s a common enough answer from youths like them, their colour. They’re not going to be saying they’ve been selected for the 1st Eleven at cricket or that they’re off on a student tour to Europe in the school holidays.

The spokesman, Dumile, tells her he wants to study by correspondence, ‘get his matric’ that he was preparing for two years ago; two years ago when he was still a child, when he didn’t have the hair that is now appearing on his face, making him a man, taking away the childhood. In the hesitations, the silences of the table, where there is nervously spilt coffee among plates of banana skins, there grows the certainty that he will never get the papers filled in for the correspondence college, he will never get the two years back. She looks at them all and cannot believe what she knows: that they, suddenly here in her house, will carry the AK-47s they only sing about, now, miming death as they sing. They will have a career of wiring explosives to the undersides of vehicles, they will go away and come back through the bush to dig holes not to plant trees to shade home, but to plant land-mines. She can see they have been terribly harmed but cannot believe they could harm. They are wiping their fruit-sticky hands furtively palm against palm.

She breaks the silence; says something, anything.

— How d’you like my lion? Isn’t he beautiful? He’s made by a Zimbabwean artist, I think the name’s Dube.—

But the foolish interruption becomes revelation. Dumile, in his gaze — distant, lingering, speechless this time — reveals what has overwhelmed them. In this room, the space, the expensive antique chandelier, the consciously simple choice of reed blinds, the carved lion: all are on the same level of impact, phenomena undifferentiated, undecipherable. Only the food that fed their hunger was real.

Teraloyna

A place for goats — we all must leave.

Othello called here.

That’s all it was fit for, our island. The goats. After how long we don’t know; because we don’t know how or when we got there: a shipwreck must have started us, we have one family name only — Teraloyna. But Othello stopped here; they came over in small boats, black men with spears. They did not harm us. We had always fished with nets woven of bark; they taught us to spear the great fish who broke our nets. They never went back wherever it was they came from. And so when we left we had among us only a child here and there who was raw-faced and blue-eyed; we were coloured neither very dark nor very light.

We don’t know how the goats came. Perhaps there was a pair of goats on board, for the milk, and they swam ashore from the wreck. Ours were strong, large goats, they had a great many young. They had many more young than we had; in the end they ate up the island — the grass, the trees, at night in our houses we could hear those long front teeth of theirs, paring it away. When the rains came our soil had nothing to hold it, although we made terraces of stones. It washed away and disappeared into the shining sea. We killed and ate a lot of goats but they occupied some parts of the island where we couldn’t get at them with our ropes and knives, and every year there were more of them. Someone remembered us — a sailor’s tale of people who had never seen the mainland of the world? — and we were recruited. We took our grandmothers and the survivors of our matings of father and daughter, brother and sister (we never allowed matings of mother and son, we were Christians in our way, in custom brought down to us from the shipwreck) and we emigrated to these great open lands — America, Australia, Africa. We cleaned the streets and dug the dams and begged and stole; became like anybody else. The children forgot the last few words of the shipwreck dialect we once had spoken. Our girls married and no longer bore our name. In time we went into the armies, we manned the street stands selling ice-cream and hot dogs, all over the mainland that is the world.

The goats died of famine. They were able to swim to survival from a ship, but not across an ocean. Vegetation and wildlife, altered forever by erosion, crept back: blade by blade, footprint by footprint. Sea-birds screamed instead of human infants. The island was nevertheless a possession; handed out among the leftovers in the disposition of territories made by victors in one or other of the great wars waged on the mainland. But neither the United States nor Britain, nor the Soviet Union, was interested in it; useless, from the point of view of its position, for defence of any sea-route. Then meteorologists of the country to which it had been given found that position ideal for a weather station. It has been successfully manned for many years by teams of meteorologists who, at first, made the long journey by ship, and more recently and conveniently by plane.

A team’s tour of duty on the island is a year, during which the shine of the sea blinds them to the mainland as it did those who once inhabited the island. A long year. A plane brings supplies every month, and there is communication by radio, but — with the exception of the goats, the islanders must have kept goats, there are the bones of goats everywhere — the team has neither more nor less company than the islanders had. Of course, these are educated people, scientists, and there is a reasonable library and taped music; even whole plays recorded, someone in one of the teams left behind cassettes of Gielgud’s Lear and Olivier’s Othello — there is a legend that Othello was blown in to anchor at the island. The personnel are subject to the same pests the original inhabitants suffered — ticks, mosquitoes, recurrent plagues of small mice. Supposedly to eat the mice, but maybe (by default of the softness of a woman?) to have something warm to stroke while the winter gales try to drown the weather station in the sea that cuts it adrift from humankind, a member of a team brought two kittens with him from the mainland on his tour of duty. They slept in his bed for a year. They were fed tit-bits by everyone at that table so far from any other at which people gather for an evening meal.

The island is not near anywhere. But as it is nearest to Africa, when the islanders left towards the end of the last century, some went there. Already there were mines down in the south of the continent and the communities of strangers diamonds and gold attract; not only miners, but boardinghouse- bar- and brothel-keepers, shopkeepers and tradesmen. So most of the islanders who went to Africa were shipped to the south and, without skills other than fishnet-making and herding goats — which were redundant, since commercially-produced nets were available to the fishing fleets manned by people of mixed white, Malay, Indian and Khoikhoi blood, and only the blacks, who minded their own flocks, kept goats — they found humble work among these communities. Exogamous marriage made their descendants’ hair frizzier or straighter, their skin darker or lighter, depending on whether they attached themselves in this way to black people, white people, or those already singled out and named as partly both. The raw-faced, blue-eyed ones, of course, disappeared among the whites; and sometimes shaded back, in the next generation, to a darker colour and category — already there were categories, laws that decreed what colour and degree of colour could live where. The islanders who were absorbed into the darker-skinned communities became the Khans and Abramses and Kuzwayos, those who threaded away among the generations of whites became the Bezuidenhouts, Cloetes, Labuschagnes and even the Churches, Taylors and Smiths.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Jump and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.