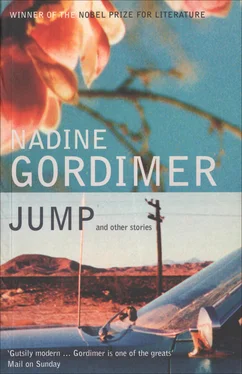

Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Jump and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Paperbacks

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Jump and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Jump and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a vivid, disturbing and rewarding portrait of life in South Africa under apartheid.

Jump and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Jump and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The moon on its back.

One of the first things he will have noticed when he arrived was that the moon in the Southern Hemisphere lies the wrong way round. The sun still rises in the east and sets in the west but the one other certainty to be counted on, that the same sky that covers the village covers the whole earth, is gone. What greater confirmation of how far away; as you look up, on the first night.

He might have learnt a few words on the ship. Perhaps someone who had preceded him by a year or so met him. He was put on a train that travelled for two days through vineyards and mountains and then the desert; but long before the ship landed already he must have been too hot in the suit, coming south. On the high plateau he arrived at the gold mines to be entrusted to a relative. The relative had been too proud to have explained by post that he was too poor to take him in but the wife made this clear. He took the watch-making tools he had been provided with and went to the mines. And then? He waylaid white miners and replaced balance wheels and broken watch-faces while-you-wait, he went to the compounds where black miners had proudly acquired watches as the manacles of their new slavery: to shift work. In this, their own country, they were migrants from their homes, like him. They had only a few words of the language, like him. While he picked up English he also picked up the terse jargon of English and their languages the miners were taught so that work orders could be understood. Fanagalo: ‘Do this, do it like this’. A vocabulary of command. So straight away he knew that if he was poor and alien at least he was white, he spoke his broken phrases from the rank of the commanders to the commanded: the first indication of who he was, now. And the black miners’ watches were mostly cheap ones not worth mending. They could buy a new one for the price he would have to ask for repairs; he bought a small supply of Zobo pocket watches and hawked them at the compounds. So it was because of the blacks he became a business man; another indication.

And then?

Zobos were fat metal circles with a stout ring at the top and a loud tick tramping out time. He had a corrugated-tin-roofed shop with his watch-maker’s bench in a corner and watches, clocks and engagement and wedding rings for sale. The white miners were the ones whose custom it was to mark betrothals with adornments bought on the instalment plan. They promised to pay so-much-a-month; on the last Friday, when they had their wages, they came in from the hotel bar smelling of brandy. He taught himself to keep books and carried bad debts into the Depression of the Thirties.

He was married, with children, by then. Perhaps they had offered to send a girl out for him, a home girl with whom he could make love in his own language, who would cook according to the dietary rules. It was the custom for those from the villages; he surely could have afforded the fare. But if they knew he had left the tin shack behind the shop where he had slept when first he became a business man, surely they couldn’t imagine him living in the local hotel where the white miners drank and he ate meat cooked by blacks. He took singing lessons and was inducted at the Masonic Lodge. Above the roll-top desk in the office behind his new shop, with its sign WATCHMAKER JEWELLER & SILVERSMITH, was an oval gilt-framed studio photograph of him in the apron of his Masonic rank. He made another move; he successfully courted a young woman whose mother tongue was English. From the village above which the moon turned the other way there came as a wedding gift only a strip of grey linen covered with silk embroidery in flowers and scrolls. The old woman who sat on the bench must have done the needlework long before, kept it for the anticipated occasion, because by the time of the distant marriage she was blind (so someone wrote). Injured in a pogrom — was that a supposition, an exaggeration of woes back there, that those who had left all behind used to dramatize an escape? More likely cataracts, in that village, and no surgeon available. The granddaughters discovered the piece of embroidery stuck away behind lavender-scented towels and pillowcases in their mother’s linen cupboard and used it as a carpet for their dolls’ house.

The English wife played the piano and the children sang round her but he didn’t sing. Apparently the lessons were given up; sometimes she laughed with friends over how he had been told he was a light baritone and at Masonic concerts sang ballads with words by Tennyson. As if he knew who Tennyson was! By the time the younger daughter became curious about the photograph looking down behind its bulge of convex glass in the office, he had stopped going to Masonic meetings. Once he had driven into the garage wall when coming home from such an occasion; the damage was referred to in moments of tension, again and again. But perhaps he gave up that rank because when he got into bed beside his wife in the dark after those Masonic gatherings she turned away, with her potent disgust, from the smell of whisky on him. If the phylacteries and skull-cap were kept somewhere the children never saw them. He went fasting to the synagogue on the Day of Atonement and each year, on the anniversaries of the deaths of the old people in that village whom the wife and children had never seen, went again to light a candle. Feeble flame: who were they? In the quarrels between husband and wife, she saw them as ignorant and dirty; she must have read something somewhere that served as a taunt: you slept like animals round a stove, stinking of garlic, you bathed once a week. The children knew how low it was to be unwashed. And whipped into anger, he knew the lowest category of all in her country, this country.

You speak to me as if I was a kaffir.

The silence of cold countries at the approach of winter. On an island of mud, still standing where a village track parts like two locks of wet hair, a war memorial is crowned with the emblem of a lost occupying empire that has been succeeded by others, and still others. Under one or the other they lived, mending shoes and watches. Eating garlic and sleeping round the stove. In the graveyard stones lean against one another and sink at levels from one occupation and revolution to the next, the Zobos tick them off, the old woman shelling peas on the bench and the bearded man at the dockside are in mounds that are all cenotaphs because the script that records their names is a language he forgot and his daughters never knew. A burst of children out of school alights like pigeons round the monument. How is it possible that they cannot be understood as they stare, giggle and — the bold ones — question. As with the man in the train: from the tone, the expression on the faces, the curiosity, meaning is clear.

Who are you?

Where do you come from?

A map of Africa drawn with a stick in the mud.

Africa! The children punch each other and jig in recognition. They close in. One of them tugs at the gilt ring glinting in the ear of a little girl dark and hairy-curly as a poodle. They point: gold.

Those others knew about gold, long ago; for the poor and despised there is always the idea of gold somewhere else. That’s why they packed him off when he was thirteen and according to their beliefs, a man.

At four in the afternoon the old moon bleeds radiance into the grey sky. In the wood a thick plumage of fallen oak leaves is laid reverentially as the feathers of the dead pheasants swinging from the beaters’ belts. The beaters are coming across the great fields of maize in the first light of the moon. The guns probe its halo. Where I wait, apart, out of the way, hidden, I hear the rustle of fear among creatures. Their feathers swish against stalks and leaves. The clucking to gather in the young; the spurting squawks of terror as the men with their thrashing sticks drive the prey racing on, rushing this way and that, no way where there are not men and sticks, men and guns. They have wings but dare not fly and reveal themselves, there was nowhere to run to from the village to the fields as they came on and on, the kick of a cossack’s mount ready to strike creeping heads, the thrust of a bayonet lifting a man by the heart like a piece of meat on a fork. Death advancing and nowhere to go. Blindness coming by fire or shot and no way out to see, shelling peas by feel. Cracks of detonation and wild agony of flutter all around me, I crouch away from the sound and sight, only a spectator, only a spectator, please, but the cossacks’ hooves rode those pleading wretches down. A bird thuds dead, striking my shoulder before it hits the soft bed of leaves beside me.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Jump and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.