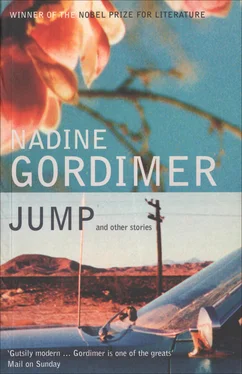

Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - Jump and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Jump and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Paperbacks

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Jump and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Jump and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a vivid, disturbing and rewarding portrait of life in South Africa under apartheid.

Jump and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Jump and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Describe it.

She gazed straight at him, turned her head to direct those eyes away, and began to speak. Very elaborate, she said, platinum and gold… you know, it’s difficult to be precise about an object you’ve worn so long you don’t notice it any more. A large diamond… several. And emeralds, and red stones… rubies, but I think they had fallen out before…

He went to the drawer in the hotel desk-cum-dressing-table and from under folders describing restaurants, cable TV programmes and room service available, he took an envelope. Here’s your ring, he said.

Her eyes did not change. He held it out to her.

Her hand wafted slowly towards him as if under water. She took the ring from him and began to put it on the middle finger of her right hand. It would not fit but she corrected the movement with swift conjuring and it slid home over the third finger.

He took her out to dinner and the subject was not referred to. Ever again. She became his third wife. They live together with no more unsaid, between them, than any other couple.

My Father Leaves Home

The houses turn aside, lengthwise from the village street, to be private. But they’re painted with flowery and fruity scrolls and garlands. Blossoming vines are strung like washing along the narrow porches’ diminishing perspective. Tomatoes and daisies climb together behind picket fences. Crowded in a slot of garden are pens and cages for chickens and ducks, and there’s a pig. But not in the house he came from; there wouldn’t have been a pig.

The post office is made of slatted wood with a carved valance under the roof — a post-office sign is recognizable anywhere, in any language, although it’s one from a time before airmail: not a stylized bird but a curved post-horn with cord and tassels. It’s from here that the letters would have gone, arranging the passage. There’s a bench outside and an old woman sits there shelling peas. She’s wearing a black scarf tied over her head and an apron, she has the lipless closed mouth of someone who has lost teeth. How old? The age of a woman without oestrogen pills, hair tint charts, sun-screen and anti-wrinkle creams. She packed for him. The clothes of a cold country, he had no other. She sewed up rents and darned socks; and what else? A cap, a coat; a boy of thirteen might not have owned a hand-me-down suit, yet. Or one might have been obtained specially for him, for the voyage, for the future.

Horse-drawn carts clomp and rattle along the streets. Wagons sway to the gait of fringe-hooved teams on the roads between towns, delaying cars and buses back into another century. He was hoisted to one of these carts with his bag, wearing the suit; certainly the cap. Boots newly mended by the member of the family whose trade this was. There must have been a shoemaker among them; that was the other choice open to him: he could have learnt shoe-making but had decided for watch-making. They must have equipped him with the loupe for his eye and the miniature screwdrivers and screws, the hairsprings, the fish-scale watch glasses; these would be in his bag as well. And some religious necessities. The shawl, the things to wind round his arm and brow. She wouldn’t have forgotten those; he was thirteen, they had kept him home and fed him, at least until their religion said he was a man.

At the station the gypsies are singing in the bar. It’s night. The train sweats a fog of steam in the autumn cold and he could be standing there somewhere, beside his bag, waiting to board. She might have come with him as far as this, but more likely not. When he clambered up to the cart, that was the end, for her. She never saw him again. The man with the beard, the family head, was there. He was the one who had saved for the train ticket and ship’s passage. There are no farewells; there’s no room for sorrow in the drunken joy of the gypsies filling the bar, the shack glows with their heat, a hearth in the dark of the night. The bearded man is going with his son to the sea, where the old life ends. He will find him a place in the lower levels of the ship, he will hand over the tickets and bits of paper that will tell the future who the boy was.

We had bought smoked paprika sausage and slivovitz for the trip — the party was too big to fit into one car, so it was more fun to take a train. Among the padded shotgun sleeves and embossed leather gun cases we sang and passed the bottle round, finding one another’s remarks uproarious. The Frenchman had a nest of thimble-sized silver cups and he sliced the sausage towards his thumb, using a horn-handled knife from the hotel gift shop in the capital. The Englishman tried to read a copy of Cobbett’s Rural Rides but it lay on his lap while the white liquor opened up in him unhappiness in his marriage, confided to a woman he had not met before. Restless with pleasure, people went in and out of the compartment, letting in a turned-up volume of motion and buffets of fresh air; outside, seen with a forehead resting against the corridor window, nothing but trees, trees, the twist of a river with a rotting boat, the fading Eastern European summer, distant from the sun.

Back inside to catch up with the party: someone was being applauded for producing a bottle of wine, someone else was taking teasing instruction on how to photograph with a newfangled camera. At the stations of towns nobody looked at — the same industrial intestines of factory yards and junk tips passed through by railway lines anywhere in the world we came from — local people boarded and sat on suitcases in the corridors. One man peered in persistently and the mood was to make room for him somehow in the compartment. Nobody could speak the language and he couldn’t speak ours, but the wine and sausage brought instant surprised communication, we talked to him whether he could follow the words or not, and he shrugged and smiled with the delighted and anguished responses of one struck dumb by strangers. He asserted his position only by waving away the slivovitz — that was what foreigners naturally would feel obliged to drink. And when we forgot about him while arguing over a curious map the State hunting organization had given us, not ethno- or geographic but showing the distribution of water- and wildfowl in the area we were approaching, I caught him looking over us, one by one, trying to read the lives we came from, uncertain, from unfamiliar signs, whether to envy, to regard with cynicism, or to be amused. He fell asleep. And I studied him.

There was no one from the hunting lodge come to meet us at the village station ringed on the map. It was night. Autumn cold. We stood about and stamped our feet in the adventure of it. There was no station-master. A telephone booth, but whom could we call upon? All inclusive; you will be escorted by a guide and interpreter everywhere — so we had not thought to take the telephone number of the lodge. There was a wooden shack in the darkness, blurry with thick yellow light and noise. A bar! The men of the party went over to join the one male club that has reciprocal membership everywhere; the women were uncertain whether they would be acceptable — the customs of each country have to be observed, in some you can bare your breasts, in others you are indecent if wearing trousers. The Englishman came back and forth to report. Men were having a wild time in the shack, they must be celebrating something, they were some kind of brotherhood, black-haired and unshaven, drunk. We sat on our baggage in the mist of steam left by the train, a dim caul of visibility lit by the glow of the bar, and our world fell away sheer from the edge of the platform. Nothing. At an unknown stage of a journey to an unknown place, suddenly unimaginable.

An old car splashed into the station yard. The lodge manager fell out on his feet like a racing driver. He wore a green felt hat with badges and feathers fastened round the band. He spoke our language, yes. It’s not good there, he said when the men of the party came out of the bar. You watch your pocket. Gypsies. They don’t work, only steal, and make children so the government gives them money every time.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Jump and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Jump and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.