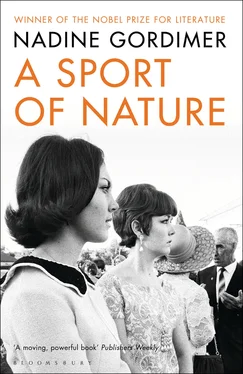

Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Sport of Nature

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sport of Nature: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Sport of Nature»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Sport of Nature — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Sport of Nature», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I got lost somewhere a few pages back. Even now — specially now — you must know just about everything, in terms of events, and the reactions of white power to events, here; and the precipitation of events by that power. But you can’t know what it has been to live here, I hated everyone in the house for not having a solution, because I was like Pauline, I was looking for one myself. Pretending not to be. Not arriving at one, through my skin. I’ve always been afraid to feel too much, the only time I did it was all so painful, such a mess. But in the Seventies everything changed. Pauline and her crowd were told they could not look for a solution — it was not for them: something like a state of grace, they couldn’t attain it. You knew that, before then. Long before. Well, whatever your view of the Black Consciousness movement (you may be politically sympathetic or not, for all I know, it’ll be a matter of alliances, now, although you were a loyal kid in your own way and surely your ANC ties prevail, whichever way your President/husband inclines) — whatever you think, Black Consciousness, black withdrawal freed us whites as much as it reduced us to despair. Despair for my mother; she packed up Joe and Carole and went to London. Me — it freed me. There was nothinga white could do in ’76 when the black students had the brilliant idea of beginning the revolution at the beginning of blacks’ lives: in school. Don’t believe anybody who claims to know who exactly should take the credit. SASO has a good share, underground ANC has some, but there were so many little groups with long titles that became proper nouns in the acronymic language we communicate in now. It was spontaneity that created its own structures, but the form action took was old as revolt itself, as oppression itself. The demands arose first from the apparently narrow orbit of children’s lives — the third-rate education, the prohibition of students’ councils, the objection to Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. But this was another Kamhlaba—‘a world’ of a different kind from Pauline’s failed solution for me, a real microcosm of real social conditions under which blacks live. These childish demands could be met only by adult answers. What the young really were doing was beginning to put their small or half-formed bodies under the centuries’ millstone. And they have lifted it as no adult was able to do, by the process of growing under the weight, something so elemental that it can no more be stopped than time can be turned back. They have lifted it by the measure of more than ten years of continuous revolt — pausing to take breath in one part of the country, heaving with a surge of energy in another — and by showing their parents how it can be done, making room through the ’80s for new adult liberation organizations — you’ve heard about the UDF *—for militancy in the trade unions and churches .

That’s where I come in — came in. If you couldn’t wait, I suppose you had to go: Pauline went. There was nothing for whites to do but wait to see what blacks might want them to do. There was a lot of shit to take from them — blacks. Why should I be called whitey? I didn’t ever say ‘kaffir’ in my life. Not being needed at all is the biggest shit of the lot. But everything was changing — no, the main thing was changing. Not the laws, the whites were only tinselling them up for travel brochures. (You could marry your black husband here, now, but you couldn’t buy our old house and move in. Though you could live illegally in a Hillbrow that and get away with it; apartheid is breaking down strangely where everyone said it never would — among the less affluent whose jobs are at risk from black competition …) The main other thing was changing, the thing far more important than the laws, in the end. Blacks of all kinds and ages were deciding what had to be done and how to do it. Even the white communists, people like Fischer and Lionel Burger, hadn’t recognized quite that degree of initiative in blacks, before, they’d always at least told blacks how they thought it could be done; and even the ANC in its mass campaigns had responded to what whites had done rather than forced whites into situations where they were the ones who had to respond to blacks. Now it didn’t matter whether it was one of the black bourgeoisie the radicals said were being co-opted by the white system, a businessman like Sam Motsuenyane getting British banks to make their South African operation acceptable by putting up capital for a black bank and training blacks to run it, or whether it was kids willing to be shot rather than educated for exploitation, or whether, from ’79, it was the bosses forced to admit they couldn’t run industry without a majority of unionised labour with which to negotiate. It wasn’t any longer a question of justice, it was a question of power the whites were confronted with. Justice is high-minded and relative, hey. You can give people justice or withhold it, but power they find out how to take for themselves. There are precedents for them to go by — and whites on the black side had tried to establish these — but no rules except those that arise pragmalically from the circumstances of people’s lives. That’s why text-book revolutions fail, and this one won’t. Castro made a revolution with fifteen followers. Marcos was driven out to exile by Filipinos who simply swarmed around his military vehicles like ants carrying away dead vermin — they’d judged by then he couldn’t will his soldiers to fire into crowds. I know it’s said that Reagan saw the game was up for Marcos and that’s why the troops didn’t shoot — but that’s not the whole story. The slave knows best how to test his chains, the prisoner knows best his jailer. (How did I persuade Hendrik to bring me this paper!) The way we’ve lived here hasn’t been quite like anything anywhere else in the world. The blacks came to understand that to overthrow that South African way of life they’d have to find methods not quite like anything that’s succeeded anywhere else in the world .

What a lucid patch I’ve struck. But where I came in: I wrote you about that, in the letter that was returned. I saw no point in becoming Joe (though I still admire my father) but the legal studies I’d been dragging myself through were a good background for what did come up. Something blacks did turn out to want was whites to work for them in the formation of unions, people with a knowledge of industrial legislation. They gave me a job. When the United Democratic Front was launched, and the unions I was working for affiliated, I got drawn in along with them, by then, blacks had sufficient confidence to invite whites to join the liberation struggle with them, again. They have no fear it’ll ever be on the old terms. Those’ve gone for good. So you’re not the only one who’s spoken on public platforms. I was up there, too. There’s not much corporate unionism among blacks — you know what that means? Unions that stick to negotiating wage agreements, safety, canteen facilities and so on. Our unions don’t see their responsibility for the worker ending when he leaves the factory gates every day. Their demands aren’t only for the baas, they’re addressed to the government, black worker power confronting white economic power, and they’re for an end to the South African way of life .

There’ve been a great many funerals. The law can stop the public meetings but not always the rallies at funerals of riot dead — although the law tries. Sometimes the police Casspirs and the army follow people back to the washing of the hands at the family’s house, and the crowd gathered there is angry at the intrusion on this custom and throws stones, and the army or police fire. Then there is another funeral. This has become a country where the dead breed more dead. But you’ve seen these scenes of home on your television in State House. There were plenty of television crews to record them before the law banned coverage. And clandestine filming still goes on. I can imagine that, Hillela — you sitting watching us — but of course you look about eighteen years old, and now — good god, you must be forty. You also see the madness that this long-drawn-out struggle has bred. Your traitor was lucky, he was white and he flitted long ago. The blacks who inform have roused madness in ordinary people. Necklaces of burning tyres placed over informers’ heads, collaborators’ heads, and packs turning on a suspect among themselves and kicking him to death. ‘Her’, too; I was at a funeral of a unionist, shot by the police, and some youngsters followed the cry that a girl had been recognized as an informer and each brought down upon her blows that combined to kill her. You know how people come up to a grave one by one and throw their flower in, as a tribute? Well, each gave their blow. Mistakes are made sometimes; that is sure. I don’t know if that girl was what the crowd thought she was, or if she just happened to resemble a culprit. And the manner of dealing with culprits. What happened to the smiling grateful kids who used to come to free classes at the old church on Saturdays — even you gave them a Saturday or two, didn’t you, before you found there were better things to pass the time. They boycotted the Bantu Education that made it necessary for them to receive white charity coaching, they got shot at and tear-gassed after you’d gone, there’ve been funerals for many of them. Does bravery, awesome contempt for your own death take away all feeling? (White kids don’t even know what death is, we were kept away from funerals for fear of upsetting us psychologically.) Can you kill others as you may be killed — and do even worse? And is this death really worse than death by police torture? Whites don’t call their fellow whites savages for what goes on in this building .

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Sport of Nature» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.