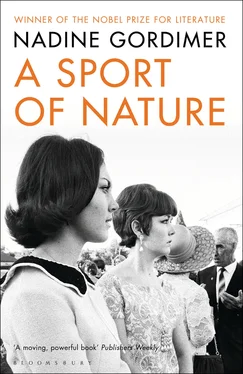

Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Sport of Nature

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sport of Nature: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Sport of Nature»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Sport of Nature — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Sport of Nature», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There’s nothing more to dread. Is there? If they put me on trial and the skills of all Joe’s colleagues can’t get me off, I’ve stood it for seven months in prison, if I go in for years, I won’t have to die that death again .

I’m going to tell you that at first Pauline actually had the idea you might be able to ‘do something’ about me! Olga recognized you in a newspaper photograph, Hillela is Madame la Prèsidente. How you got there, that’s confusing, too. When I wrote some years ago you were supposed to be married to an American professor, but the letter came back. Pauline was in one of her hyped-up states when she arrived here: you would get your President to pull strings. What strings? Through the OAU; she had rushed off to one other old chums still teaching African Politics at Wits and checked your husband’s standing, which proved high. Joe had to point out that the OAU was not exactly influential with the South African security police. It was only a lapse; my mother’s really always been cleverer than Joe, we know. She’s still here. I realize she’ll never go back while I’m inside. She’s tremendously active with a group that supports us — detainees, and politicals on trial. It’s possible she might land up inside, too. She looks wonderful. I’ll tell you: happy. She’s the only person I see except the Major’s team, and Hendrik and his mates in uniform. The visits are in the presence of warders, you can’t say much, but all Pauline and I have to say to each other is political and we’ve come to some strange kind of intuition between us, a private language by which we’re able to convey information back and forth in a form Hendrik and co. can’t follow. Family sayings, childhood expressions — we have access through them .

Then why do I say I’m incommunicado .

You couldn’t experience it, of course, being more or less a lucky orphan, but hearing from outside exclusively in the voice of your mother, it’s like being thrust up back again into the womb .

I can never guess whether you’ll be interested or not. Because I can’t imagine what your life is. If I think of you in the morning, for instance, I can’t imagine where you get up out of bed as you used to in your short pyjamas, that kind of baby dress with bikini pants, you having breakfast — what sort of room, not a kitchen! — you going off to do what? What do you do all day in a President’s house? State House — Groote Schuur’s the only one I’ve ever seen, and I’ll bet yours isn’t Cape Dutch-gabled. I’m lodged with the State, myself, so we’ve both landed up in the same boat, but you’re at the Captain’s table, and I’m pulling the oars down in the galley. That’s supposed to be funny, in case you think I’m dramatizing myself. I was going to say — I don’t know if you’re interested in how I got here. I don’t think it will be any surprise to you that I am. I was on my way while we were still kids, although I made a kind of nihilistic show of kicking against it. Pauline’s Great Search for Meaning. It was a pain in the arse. You went off and plink-plonked on your guitar. I sneered at her. My school — the one she chose for me, did Joe ever decide anything for us? — its Swazi name meant ‘the world’, one of those great African omnibus concepts (I love them), the nearest synonym in our language is a microcosm, I suppose. Nobody at home knew how happy I was there — certainly not you. Carole may have suspected. It was the world (and the world’s South Africa for us) the way we wanted it to be, the way Pauline longed for it to be, and into which she projected me. But it had no reality in the world we had to grow up into, less and less, now none at all. It was all back-to-front. When I went to school, I went home — to that ‘world’; when I came to the house in Johannesburg, I was cast out. Good god, even you were more at home in that house than I was. Alpheus in the garage, Pauline and Joe’s pals bemoaning the latest oppressive law on the terrace under that creeper with the orange trumpet flowers. At Kamhlaba blacks were just other boys in the same class, in the dormitory beds, you could fight with them or confide in them, masturbate with them, they were friends or schoolboy enemies. At the house, my mother’s blacks were like Aunt Olga’s whatnots, they were handled with such care not to say or do anything that might chip the friendship they allowed her to claim — and she had some awful layabouts and spivs among them. I smelt them out, because where I was at ‘home’, that sort of relationship, carrying its own death, didn’t have to exist. Poor Pauline. I hated South Africa so much .

When I was older — by the time you left the house — I hated them all, or I thought I did. Maybe even Joe. I expected them to have solutions but they only had questions. Do you realize I was the only answer Pauline ever had? She knew what to do about me: sent me to Kamhlaba, ‘the world’. But I had to come back. Joe half-believed his answer: the kind of work he was doing, but you know how she was the one who took away half the certainty. And she was right, in her way, you can’t find justice in a country with our kind of laws. I feel as Bram Fischer did, that if I come to trial it’s going to be before a court whose authority I don’t recognize, under laws made by a minority government of whites. I’d like to reject that white privilege, too, but how can I take away from Joe the half he believes in? It’s all my father has. And of course if I can get off and live to fight another day, so to speak, I want that. No sense in a white being a martyr. There’s not enough popular appeal involved .

I’ve no way of knowing how much you know. I mean, you certainly know the facts of what has happened in this country since you left. After all, you were married to a revolutionary. You probably knew more about it, from a politico-analytical point of view, than I did, at least during the years you were with him — and that’s why I can’t imagine you, Hillela, that’s it, I can’t imagine you living your life in the tremendous preoccupation that is liberation politics. Yet it seems this has been your solution, in your own way — and I never thought of you as in need of a solution at all, I still don’t, I never shall. You know, in these places one suffers from something called sensory deprivation (Pauline’s crowd apparently have published an extensive study of this which has horrified even people who think those like me ought to be kept locked up: they’ve revised their punitive premise, they think we deserve all we get, but nobody deserves quite that). I have it, too, ‘sensory deprivation’, I won’t go into the symptoms but the incoherent jumps in this letter are well known to be one. As I said, I’m not really crazy, and they won’t get me that way. Thoughts are wonderfully free when you’re in this state of sensory deprivation. Some hallucinate but it’s not that with me. It makes me know things I didn’t know. About you, Hillela. You were always in the opposite state. You received everything through your skin, understood everything that way. I suppose you still do. One can’t judge change in others by change in oneself .

They said you went because of the journalist chap. A solution. D’you know he was almost certainly working for the security police? The whole business of raiding the cottage where you lived with him was a put-up job, to keep his credibility and make him appear to have to flee the country so he could carry on his slimy trade in Dar es Salaam? Apparently the ANC blew his cover there, I heard the whole story only recently. Well, at least nothing happened to you. What do you look like, Hillela. I didn’t see the newspaper photograph with you sitting next to Yasir Arafat (imagine Olga’s face) .

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Sport of Nature» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.