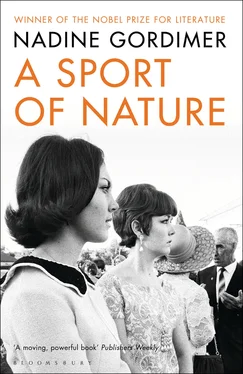

Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Sport of Nature

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sport of Nature: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Sport of Nature»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Sport of Nature — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Sport of Nature», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But there was no consequence at the school. If the Calder girl and her parents were summoned to the headmistress’s study, the girl herself was so well-brought-up that she had already the confidence of her kind to avoid any challenge of it. Nothing short of a revolution, the possibility of which was inconceivable to such confidence, could really harm it. So why bother to defend oneself? She and her accuser, Carole, took the opportunity to pretend the words had never been said or heard. Carole, as she moved up into senior positions in the school, became influential in the debating society and was able to introduce such subjects as ‘Should there be censorship?’ to girls whose parents read detective stories and best-selling sex novels while in her home banned books about South African life and laws were passed around and discussed. She even managed to have approved for debate ‘Should there be different standards of education for black and white children?’ though most of the girls had not heard that ‘Bantu Education’ had been introduced in the country, and there was a better attendance for ‘Should we have sex education at school?’ A self-service canteen had replaced the black waiters, for reasons of economy. Carole and Hillela, at Pauline’s suggestion, arranged to have black children invited to a special performance of the school’s production of Peter Pan ; still schoolgirls themselves, Carole and Hillela were so advantaged (as Pauline reminded them) by their educational opportunities at school and by home background that they were able to help coach black students who came in from the townships to the centre run by Pauline’s supplementary education committee, KNOW. The two girls were kept occupied on Saturday mornings in a red-brick church that once must have been in the veld outside the black miners’ compounds but was by then hemmed in by workshops and industrial yards. Its ivy hung ragged from its porch and in the bushes that had been a garden were trampled places where, Pauline told, homeless black people slept. Their rags and their excreta made it necessary to watch where you set your feet; but the black boys and girls who came up singing in harmony — now mellow, now cricket-shrill — between the broken ornamental bricks of the path gave off the hopefulness of sweet soap and freshly-ironed clothes. It was in return for their lessons that they sang, and whenever they sang those whose enviable knowledge subdued the children into shy incomprehension in class became the uncomprehending ones: Mrs Pauline and her colleagues, and the two white schoolgirls, smiling, appreciative. Pauline asked what the songs meant and wrote it down for quotation in the committee’s letter of appeal for funds. (—Look at this tip left under the plate. — She waved before her family Olga’s response: a cheque for ten pounds.) Hillela was heard singing the songs in the shower. Recalled — by this sign of musicality he had not had the chance to develop in himself — from absorption in documents of the treason trial whose level of reality made all other aspects of the present become like a past for him, Joe bought her a guitar.

— Where on earth’d you find time to look for that?—

He answered Pauline gravely as if under oath. — In Pretoria. During the lunch adjournment. In a music shop.—

— And now? — Pauline’s smile quizzed gestural asides; she was the one who had to complete these for their initiators. Hillela and her uncle came together and hugged — people who have fallen in love for a moment; but it was Pauline who arranged for Hillela to have lessons with the folk-guitarist son of one of Pauline’s friends. Hillela was soon accomplished enough to play and sing in a language she understood, performing Joan Baez songs at protest meetings to which Joe and Pauline gave their support: against the pass laws, apartheid in the universities, removals of black populations under the Group Areas Act. Carole, like her cousin, was under age to be a signatory to petitions but could take a turn at manning tables where they were set out. The two adolescents were absorbed into activities in which a social conscience had the chance to develop naturally as would a dress-sense under Olga’s care.

Family likeness was to be recognized in Pauline, for one who had once been the daughter Olga never had. A girl younger than Hillela was brought to the house by Joe; but a schoolgirl with the composure of someone much older. On her the drab of school uniform was not a shared identity but a convention worn like a raincoat thrown over the shoulders. She turned the attention of a clear smile when spoken to yet, as an adult gets out of the way polite acknowledgement of the presence of children, firmly returned the concentration of her grey eyes to Joe, who read through documents those eyes were following from familiarity with the contents. Pauline spread cream cheese, strewed a pollen of paprika, shaved cucumber into transparent lenses and opened a tin of olives. She sniffed at her hands and washed them in the sink before carrying into the livingroom the mosaic of snacks worthy of her sister Olga. The girl drank fruit juice and ate steadily without a break in the span of the room’s preoccupation, while Pauline hovered with small services in the graceful alertness of a cocktail party hostess.

— D’you know who that was? — Pauline came into the bedroom where Carole and Hillela had holed up.

— Daddy said. Rose somebody. I see she goes to Eastridge High. Horrible school.—

Pauline’s vivid expression waited for its import to be comprehended. — That’s Rosa Burger. Both her parents are in prison.—

Theirs was one of the trials in which Joe was part of the legal defence team. The red-haired handsome woman with the strut of high insteps who had accompanied the Burger girl was also one of the accused, though out on bail, like the old black gentleman who came to stay in Pauline and Joe’s house for a few weeks. There were discussions about this, at table, before it happened; the old man had some illness or other and dreaded, Joe said, the strain of travelling from Soweto to the court in Pretoria every day. Hotels did not admit black people. Sasha’s room was made ready for the guest; then Pauline decided it was too hot, the afternoon sun beat through the curtains, and Carole and Hillela were moved out of their room, for him.

There was a rose in a vase on the bedside table. Although Alpheus occupied the converted garage, no black person had ever slept in the house before. The old gentleman really was that — a distinguished political leader and also a hereditary chief who was to be addressed by his African title specifically because the government had deposed him. The ease of the house tightened while he was there. Other people who came to stay were left to fit in with the ways of the household, but there was uncertainty about what would make this guest feel at home. When he was heard hawking in the bathroom the girls shared with him, they looked at each other and suppressed laughter and any remark to members of the family. Joe put out whisky but the old gentleman didn’t take alcohol; Pauline got Bettie to squeeze orange juice; it was too acid for him. He drank hot water; so a flask was always to be ready, beside the rose. He had a magnificent head, Pauline explained; he ought to be painted, for posterity. She phoned her sister Olga, patron of the arts (let her move on from the 18th to the 20th century for once) who could tell one of her artist friends of the opportunity for sittings with someone a little different from the wives of Chairmen of Boards, someone whose life would go down in history. — My poor sister — her first reaction is always to be afraid of trouble! Would it be all right? Not cause any trouble? I think she was nervous her famous friend would land in jail for so much as committing the shape of Chief’s nose to paper.—

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Sport of Nature» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.