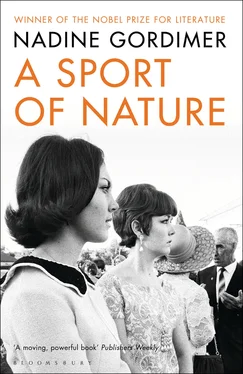

Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - A Sport of Nature» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Bloomsbury UK, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Sport of Nature

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury UK

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Sport of Nature: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Sport of Nature»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Sport of Nature — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Sport of Nature», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But she herself was no longer at the school at the end of term. She went only once again to the house with the windmill mailbox. A little girl with woolly pigtails was told — Charlene, don’t stare. — A middle-aged woman with Don’s eyes brought milky cups of tea and called Hillela ‘miss’. —My mom’s shy with people. — He said it as if she were not there; and the woman addressed Hillela in the third person: —Wouldn’t the young lady like a cold drink instead?—

The following week she was sent for by the headmistress. Len was sitting in one of the two chairs that were always placed, slightly turned towards one another, in front of the desk at which the headmistress sat. So someone had died; not long before, a girl had been summoned like this to the presence of a parent, and learned of a death in the family. Hillela stared at Len. Olga? Her other aunt, Pauline? The woman — somewhere — who was her mother? A cousin? She woke up, and went over mechanically and kissed him; he kept his face stiff, as if he had something to confess that might spill.

The headmistress began in her classroom story-telling voice. Hillela had been seen with a coloured boy. While she was enjoying on trust the privilege of going to the cinema with her classmates, she had used the opportunity to meet a coloured boy. — A pupil at a school like this one. From her kind of home. The Jewish people have so much self-respect — I’ve always admired them for that. Mr Capran, if I knew how Hillela could do what she has done, I could help her. But I cannot comprehend it. — This was not a matter of just this once. It could not be. It was not something that happened within the scope of peccadilloes recognized at a broadminded school for girls of a high moral standard. Len took Hillela away with him. All he said was (with her beside him in the car again) — I don’t understand, either.—

She felt now the fear she had not felt in the headmistress’s study. She hid in the image of Len’s little sweetheart. — I didn’t know he was coloured.—

With a father’s shyness, Len was listening for more to come.

— We all meet boys in town. — She was about to add, even when we’re supposed to be in Sunday school with the little kids. But the habit of loyalty to those who at least had been her kind, even if she couldn’t claim them any longer, stopped her mouth. She did not know whether her father knew she had been to the boy’s home. She didn’t know whether to explain about the banana loaf, a little sister who stared, the mother who called her ‘miss’. An opposing feeling was distilled from her indecision. She resented the advances of that boy, that face, those unnatural eyes that shouldn’t have belonged to one of his kind at all, like that hair, the almost real blond hair. The thought of him was repugnant to her.

Hillela stayed in Salisbury for a few days that time with Len and his wife, Billie, in their flat. He had married the restaurant hostess of an hotel — inevitable, Olga remarked, as a second choice for a lonely man in his job. What other type did he have the chance to meet? Len had brought Billie down to Johannesburg once; Hillela heard talk that she was found to be a good-hearted creature, much more sensible than she appeared, and perfectly all right for Hillela’s father. To Hillela she looked, in the tight skirt that held her legs close together as she hurried smiling between tables, like a mermaid wriggling along on its fancy tail. Olga smelled lovely when you were near her, but the whole flat and even the car smelled of Billie’s perfume, as smoke impregnates all surfaces.

Billie was exactly the same at home as in the hotel restaurant where Len treated his daughter to a meal. It was part of her professional friendliness, jokiness, to be familiar without ever prying; she no more allowed herself to mention the reason for the girl’s absence from school than she would have let a regular arriving to dine with his family know that she remembered seating him at a table for two with his mistress the week before. But on the subject of herself she was without inhibitions. At home she kept up a patter account of near-disasters between the kitchens and restaurant—‘I almost wet myself’ was her summing-up of laughter or anxiety — and expressed exasperation with those bloody stupid munts of waiters indiscriminately as she showed affection for ‘my Jewboy’—kissing Len in passing, on ear or bald patch. Neither did she care for physical privacy; ‘Come in, luv’—while the schoolgirl made to back out of the bathroom door opened by mistake. A rosy body under water had the same graceful white circlets round the waist as round the neck, like the pretty markings on some animal. The poll of fine hair dipped blonde, the same as the hair of her head, but growing out brown, was an adornment between the legs. Gold ear-rings, ankle chain and rings sent schools of fingerling reflections wriggling up the sides of the bathtub. — I could stay in for hours — I don’t blame Cleopatra, do you, fancy bathing yourself in milk … but I don’t care for the bubble stuff, Len buys it … dries out your skin, you know, you shouldn’t use it, specially in this place … my skin was so soft, at home, that rainy old climate. My sisters and me, we used to put all sorts of things in the water, anything we read about in beauty magazines. Oh I remember the mess — boiled nettles, oatmeal, I don’t know what — a proper porridge, it turned out. But we had a lot of fun. That’s the only thing I miss about England — me sisters, two of them’s still only teenagers, you know — your age. It’s a pity they aren’t nearer — (a gift she would have offered.)

The girl sat on the lavatory seat, as one of them might have done. — What are they called?—

— Oh there’s Doreen, she comes after Shirley, there’s only eleven months between them (my pa was a lively old devil). People think they’re twins, but they’re very different personalities, very different …—

— Still at school? — In the cloudy blur of the bathroom, the taboo subject lost its embarrassing reference as the woman’s body lost any embarrassment of exposure.

— Doreen couldn’t take it. She’s doing hairdressing. Shirley’s the ambitious one. She’s Scorpio. She’ll go for an advertising job, you need A-levels to get a foot in there. Or maybe a travel agency. Oh she’s always moaning how lucky her old sister is, living out here. But they’re both full of fun. A pity you don’t have any sisters … and it’s a bit late for Len and me to make one for you!—

They laughed together; like the sisters. — Oh have a baby, Billie, it doesn’t matter; have a baby. Even if it’s a boy—

— Will you come and mind it for me? Change its smelly napkins? Oooh, I’m not sure I like the idea, don’t talk me into it — In her bedroom Billie offered the loan of anything ‘you have a yen for’ in her wardrobe; like the cardboard doll on which Hillela had tabbed paper dresses when she was a small child, she held up against herself successive images of Billie, in her splendid female confidence either never naked or never dressed, advancing down the aisles of the restaurant.

Len must have cancelled his usual long-distance sales trip that kept him away from home up in Northern Rhodesia, Lusaka and the Copper Belt, from Tuesdays to Fridays. Bewilderment took the form of tact in what was — Hillela had caught the resonance of Olga’s tone in bland remarks—‘a simple soul’; he seemed to have fallen back on regarding the girl’s presence as if it were that of a normal half-term break. He did a little business round about, and kept Hillela with him. She smoked a cigarette from the pack in the glove-box and he made no remark. When she had put out the stub he turned his head away from the road, without looking at her. — My little sweetheart . — Both knew, not seeing each other, that both smiled. Balancing rocks were passing; he did not see them, either, the routes he took were worn to grooves that rose over his head and enclosed him. The moments balanced, for her, rock by rock.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Sport of Nature» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Sport of Nature» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.