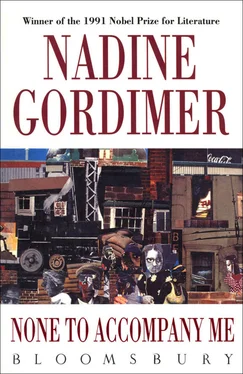

Nadine Gordimer - None to Accompany Me

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - None to Accompany Me» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Bloomsbury Paperbacks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:None to Accompany Me

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Paperbacks

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

None to Accompany Me: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «None to Accompany Me»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

None to Accompany Me — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «None to Accompany Me», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sally made a fist above her cup, she was shaking her head vehemently. — That’s just the problem. He does think he’s history. He’s copping out because he’s not centre stage any more, he sees himself as history and history stops with him. He won’t accept that it goes on being made and we all have to make it, my part has changed, his part has changed. He’s still a living man who has work to do even though it can’t be what he’d choose.—

— Writing a history? That’s the past.—

Sally leant on the table in silence but did not let it widen between them. — I came back from a trip — a mission — you’d think I’d never been away. He doesn’t bring me home.—

They are not two young women, after all, exchanging bedroom secrets. Vera may take the odd phrase as some locution for welcome slipped in from an African language. And she’s white, she has never known what exiles have, the return of your man from god knows where doing god knows what he had to do (Didymus’s name as someone connected with one of those camps luckily hasn’t become public). She may or may not have understood what Sally is saying. Didymus doesn’t bring her home by making love to her, as she used to, for him.

When Didymus did make the approaches of love-making Sibongile felt no response. Mpho had appeared from her room one evening charmed — in the sense of talented, gifted — with youth. The clarity of the lines of her body in a scrap of a dress, of her lips and long shining eyes with their fold of laughter at the outer corners, the cheap, wooden-toy ear-rings in the shape of parrots hanging from the delicate hieroglyph of her ears— she was the embodiment of happiness. Waiting to be called for; where was she going? A party, there were so many parties parents couldn’t keep up with the names of all the friends with whom she was apparently so popular. A girl-friend bustled in to fetch her, they chattered their way out. A thin chain looped through a pendant lay curled on the table where she had dropped it after lifting it from her neck over her carefully arranged hair when the friend pulled a face: the pendant clashed with the ear-rings. Didymus poured the chain from hand to hand, smiling. He came into the kitchen where Sibongile stood stirring a stew and, with the pretext of looking to see what was in the pot, leant his chin on her shoulder. His hand came round over her belly that was swelled forward as she moved the meat about with a fork, circled the navel in a half-humorous caress in anticipation of a meal, and then moved down over her pelvis a moment.

After they had eaten she seated herself at the computer they had bought for his work on the history of exiles. Staring at the luminous waver of the screen a moment, arrested, as if for some indication whether he had used it that day at all; she turned to him.

— Go ahead. — He chose to understand that she was asking whether he needed the machine now. She spilled out and sorted her papers exasperatedly. He switched on the TV, volume low in order not to disturb concentration on whatever it was she was writing. Swells of music and the exaggerated pitch of broadcast emotions emanated from where he sat, as she removed from and inserted words and phrases in a speech she was due to deliver in a few days. His back faced her every time she lifted her eyes from the juggled text swimming in phosphorescence; something about the droop of the head showed that he wasn’t seeing, he wasn’t hearing. Didymus was asleep, carried along, unconscious, like a drunk at a carnival, in the meaningless impersonal familiarity of the medium that invades everywhere and recognizes no one.

In their bed he took up the caress begun in the kitchen. His hand slid from her hips pressing firmer and firmer, smaller and smaller circles over the mound of her pubis, working fingers through the hair and slipping the index one, as if by chance, to touch through the lips. She flung back the covers and swerved out of bed, the mooring of his hand torn away. She stalked about the room with the air of looking for something and when aware of him watching her went out into the other rooms.

She came back and offered: —Verandah light wasn’t left on for Mpho.—

— I turned it on.—

— You didn’t.—

— My memory, these days …—

She lay beside him, not saying goodnight in case this provided an opening for him to try to rouse her again.

That night, or another night, she woke in a tension of sadness in which she and he were lost together, bound, sunk. The sound of their breathing strung tight between them but the divide of darkness could not be crossed, the weight of fathoms could not be lifted. He had not forgotten the light for Mpho. The pain of repentance, so useless, for this stupid little spite was actual between her ribs, something conjured up from the religious pictures pasted to the kitchen walls in her grandmother’s house in Witbank location, where she grew up. She seemed to be living simultaneously in the hum of the night all the images, the moments when she had been most aware of him, scattered through the years. Parted so often; what happens in these partings, his, now hers, in the one who goes away? Is the one who left ever the one who comes back? There are changes in understanding and awareness that can occur only when one is alone, away from containment in the shape of self outlined by another. Such changes can never be shared. Alone with them for ever. The images are postcards sent from countries that exist only in the personality of the subject; you will never visit them. She had to make sure that he was there, some version of himself, even as a shrouded bulk under the bedclothes. She hesitated where to touch him: on the forehead, the hand pressed against a cheek, the neck below the ear, where a pulse answers. She rested her spinal column back to back along the length of his and felt him break wind as he slept.

Chapter 11

The old man occupied Annick’s room, so she would have to take what had been Ivan’s and the friend she was bringing would have to share it with her. Ivan’s luxury had been a double bed across which he liked to stretch diagonally his adolescent sprawl. Vera bought a divan to move into the room to accommodate the friend. The old man’s presence already had changed the balance of the house. Sally forgot or had been too busy to fulfil her offer but connections at the Foundation supplied a relative in need of work; the path of the old man’s movements, on the arm of the woman who came to help him every day, intersected and deflected those of Vera and Ben. Vera’s house had the transparent grids of various presences laid upon it — the brief comings and goings of the soldier whose military kit propped against her dressing-table left in the varnish a dent whose cause was forgotten, the clandestine movements Bennet brought in as a lover and established in usage as husband and father, the route the children used to take, out of the window in Annick’s room and in through the back stoep door to get at potato chips in the kitchen cupboard without alerting parents, and the invisible trails of Vera herself, changing the function of a space by bringing Blue Books and White Papers to occupy what had held model plane kits and threadbare stuffed animals, closing windows room by room in a storm, carrying, as if following back in footsteps that have worn grooves in the wood floor of her house, an old photograph to the light. On her barefoot morning scamper to the bathroom the old man might cross her path, wavering ahead with his paralysed hand dangling curled at his side and the other held before him as a blind man senses for obstacles. He was not blind but formed the precautionary habit of keeping the hand in the position of one ready to receive a handshake greeting, because even that side of his body had not survived the stroke unimpaired and it took time and effort to muster the appropriate muscles when the occasion came. She had to remember to wear a gown, as she had done when there were still children at home and a live-in maid coming early from the kitchen to house-clean.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «None to Accompany Me»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «None to Accompany Me» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «None to Accompany Me» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.