— Not some kind of dope, I can tell you — kitsch, if you’re able to recognize it when you see it.—

— I still think you had the wrong lawyer. You’re just too well-brought-up, Julie, Northern Suburbs clean-hands stuff, God-on-Sundays only sees a sparrow fall, girl, he doesn’t deliver thou-shalt-not to corporate fixings but he ordains it isn’t nice to use crooked lawyers. You can’t tell me something couldn’t be fixed. Christ, the top man down at Home Affairs here has just been relieved of his job, grounds of corruption …—

Julie is sounding the wood of The Table with spread fingers. — I’m not so innocent, not of what’s done where I come from or at Home Affairs. It’s just what you’ve suggested that’s the problem. When it comes to fixing. No fancy scruples. We’ve got it on good authority that everyone down there is scared stiff to open a hand, now. He’d only find himself arrested for offering bribes, in addition to everything else—

— Naa-arh … the higher you go the less chance you have of being reached. You can’t tell me that with the right connections …—

Thinking of her father, yes; there’s always been an undercurrent of keen awareness of her father’s money The Table concealed from Julie, in contrast with the lack of vintage Rovers in the background of this speaker and others among the friends. The exceptions — her fellow escapees from the Northern Suburbs — know that Nigel Ackroyd Summers would not approach a cabinet minister with whom he dines to ask that this illegal alien from a backward country should continue to sleep with his daughter. From one of them, a quick dismissal: —That’s just not on, Andy.—

— But you can’t tell me …—

— If all those hundreds — thousands — get away with it, there must be a solution. You have to ask around. Everywhere.—

Where is there?

She waits for answers that do not come; the friends have always huddled together with solutions for everything that happens to any one of them. The alternative solutions of alternative lives?

Even if it were only, in the life of the one sitting among them every day under life-sentence of AIDS, to transform the news from unbearable to the solace of laughter, that time.

— Disappear, my Brother. Like I say.—

Their old hanger-on, the poet, has been present, silent through repetitions of the story. He folds a sheet torn from his chap-book on which he’s just written something and pushes it into her hand.

Back at the cottage she comes upon a crackling in the shirt pocket over her left breast. She feels about the pocket everywhere, ask everywhere takes out a bit of paper, distrait, he is drinking water, one glass, two glasses, deep swallows over the sink, he gasps with the last and slowly shakes his head. She unfolds the paper and reads what is there.

‘This isn’t all but it’s the first part and it’s by someone called William Plomer you wouldn’t know of.

Let us go to another country

Not yours or mine

And start again.

To another country? Which?

One without fires, where fever

Lurks under leaves, and water

Is sold to those who thirst?

And carry dope or papers

In our shoes to save us starving?

Hope would be our passport,

The rest is understood

Just say the word.

(Sorry, don’t remember how it ends.)’

She has read it aloud to him, but it is meant for her.

Dumb.

Might as well be. When they are talking about matters you know better than they do or ever will. You are dumb if you can’t speak — speak their language as they do. You have to use your lips and tongue for the other purpose, your penis and even the soles of your feet, caressing hers in the bed, in place of your opinions, convictions.

What use is that, now?

He can’t make love. She has never experienced this with any other of her lovers. Without saying anything to her he takes the car — where has he gone? He comes back with the belongings he had left in his grease-monkey outhouse at the garage. The canvas bag with frayed labels addressed in that unfamiliar script sags on the floor of the room where they have eaten and slept, together.

He asks her if she knows where he can get a cheap air ticket. Of course she knows; her work with those pop groups and conference personnel means she has contacts with travel agencies and airlines. And then she’s looking at him, into him, in disbelief, as he speaks.

You’ll do it for me? Or find where I must do it.

Her breasts are rising and falling under the sweater and the nostrils of her fine nose (he has never thought her beautiful but has always, since the first day when he came out from under a car, thought it so) are stiffened and flared. Something will happen, tears, an outburst — he must come quickly over to avert whatever it may be, he has his arms around her as you might resort to putting a hand over someone’s mouth.

What she is struggling with, not only in this moment of practical confrontation but all the time, the days that are crossed off with every coming of the light through the gap in the curtains above the bed where they lie, cannot be discussed with him. Not yet.

Disappear. Like I say.

Either way. He disappears into another city, another identity, keeps clear; or he disappears into deportation.

They go back again at night to the EL-AY Café, away from the silence in the cottage and the slumped canvas bag, because there’s usually likely to be there someone to whom she has always felt closest, among the friends.

The struggle stays clenched tightly inside her. It possesses her, alien to them, even to those she thought close; and makes them alien to her. She feels she never knew them, any of them, in the real sense of knowing that she has now with him, the man foreign to her who came to her one day from under the belly of a car, frugal with his beautiful smile granted, dignified in a way learnt in a life hidden from her, like his name. Her crowd, Mates, Brothers and Sisters. They are the strangers and he is the known.

So what’s happening?

— A bloody shame. They glide in and out of immigration at the airports with cocaine stuck up their arse, ecstasy in their vagina — and I don’t mean the kind that makes them come — but he gets turned down and kicked out.—

Neither the indignation nor the sympathy count; these are simply tonight’s subjects for the usual animation and display. Let’s get some more wine, you need a drink, Julie, come on Abdu, you too. Someone passes a joint, that’s probably more like what an oriental prince needs. The poet is not there. There is no-one. There will be no-one, for her, in this city, this country.

The two don’t drink or smoke and they leave early. The empty space they occupied at The Table is a silence; broken: —It’s not the end of the world. Our girl’s been in love a few times, as we’re well aware.—

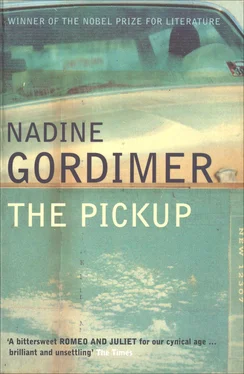

— This pickup of hers’s been a disaster from the beginning.—

— Come on, he’s not a bad guy, he just needed a meal ticket. A bed. And he obviously knew how to occupy it.—

— I’ve never seen her like this. Bad, man.—

A recent addition to The Table passes a hand over his shaven head, staring as if to follow the path The Table’s intimate and the foreigner are making through Saturday night partying that buffets them.

— Julie should chill out.—

As there is no longer any sense in playing the grease-monkey he spends these, his last few days, in the cottage. He has no appetite but is constantly thirsty; lies on that bed that has also outlived its usefulness, with a big plastic container full of cold water on the floor beside him.

So he was there when she came home from her work with the envelope from the travel agency. She handed it to him where he lay. He delayed a moment, reading the name of the agency, with its logo of some great bird in flight, as if to convince himself of its portent. He made a slit in the top of the envelope with his nail and slid a forefinger along to open it. Inside, there were two airline tickets.

Читать дальше