— Shall I go with you to this lawyer you know of? You’d like me to be with you?—

She feels an unwarranted relief from anxiety, based on nothing, just because of this spontaneity from someone who cannot help her. No, no, she and her lover must go together.

— Any time, any time, I’m here. Sharon and I, at home. You can call, you can come. Ask the lawyer if any sort of letter of recommendation — I don’t know what the form might be — would be useful. Some guarantee for your man from this respectable and law-abiding old citizen.—

He went with her past the women gazing up to greet him from their place in the waiting-room, leading her along the corridor to the lifts, waiting, so that she would not be alone with doors gliding closed on her.

It is a fact that the Senior Counsel no longer practises law. She finds out in a roundabout way since she could not ask her father without giving an explanation of why she wants to approach the man. One among the friends — it’s David — is her source through abandoned connections he takes up on her behalf. The Table is unanimous: get in touch with the guy anyway, even if he doesn’t practise any more, he’ll still have all the stuff in his head, he’s not going to refuse advice to you, he’s seen you, he’s seen Abdu, you say, at your father’s place. How can he refuse. No way!

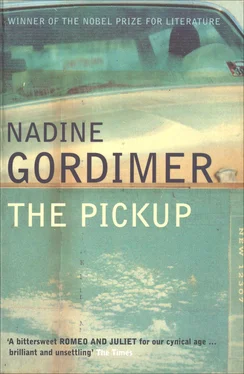

Joining them at The Table, the victim, the accused, the endangered, their friend Julie’s pickup — what is he to have the sense of, as himself? — he has listened to them closely.

— That’s what I tell her.—

You know why I’m reluctant. (In case the word escapes him): Don’t much want to.

They are like any of the combination of lovers who come and go, having a private spat between them in the protection of The Table.

So if he speaks to your father? That can be something good. If it comes from him, an important man your father likes. So if he speaks!

She gets the general secretary on the line when she calls a corporate headquarters at the number she’s been given, reaches the private secretary, then the personal assistant, and finally Mr Hamilton Motsamai himself. She has had to introduce herself to the personal assistant as Nigel Summers’ daughter. The lawyer is (in the corporate jargon she’s familiar with among her father’s associates) affable, how is Nigel, I expect to be in a meeting with him next week, very good — of course I remember you, your father’s house is a special place to relax in … yes. He has a deep soft voice, black voice, that sounds as if it would resonate from a tall broad man but she remembers he is small and agile-looking. If it’s urgent, of course. Very good. After all, this is Ackroyd’s daughter — but then oddly, as if in contradiction, she adds something awkwardly.

— I hope you don’t mind my asking — would you please not mention I’ve called you, if you do happen to be in touch with my father.—

So at once there is a secret between her and this stranger that he, her lover, will not know of. Although everything in her, is his. This is a mere filament of the strands of deviousness she is aware of having to learn in a circumstance she, in all her confident discard of conventional ones, finds she had no preparation for. He, her find; it was also this one, to be discovered in herself.

She is asked by the personal secretary, who makes the appointment, to give the registration number of her car so that she may be granted parking in the corporate headquarters’ underground bays. The good second-hand Toyota the garage mechanic obtained for her finds a place in the cavern. She looks for a moment at his avatar, presenting himself aggressively handsome in the silk scarf at the neck of the shirt that becomes him best. She smiles but he knows she is trying to measure with other eyes the impression he needs to make. They emerge through security turnstiles where they slot the plastic cards given them when the guard at the entrance verified the registration number; are guided by another uniformed man to sign (her name serves for both), time of arrival and other particulars of identification in a gold-tooled leather-bound book; are taken over by a smart young woman programmed to preface with And how are you today her instruction of which elevator goes up to the 17th floor. The doors open on a reception area before interleading halls and alcoves, like a five-star hotel; palm trees lean up to a glass dome, a fountain dribbles from the beaks of bronze cranes and under lamps there are pale leather sofas and chairs grouped for conversation. Some sort of luncheon is going on, spilling from one of the alcoves. There is the curve of a small bar, silver-bright ice buckets on stands, a buffet concealed by people helping themselves to an accompaniment of laughter and voices from which the treble jets as another kind of fountain. He and she stand: the lights have gone up in a theatre.

Mr Motsamai’s suite is reached through his secretary’s office and his personal assistant’s office, both women seal-sleekly blonde. He receives his associate’s daughter and the young man (foreign) not in the formality of his office where he does business but in his adjoining reception room, not too large for one-to-one contact, amply comfortable, with TV console and a fan of financial journals on its glass tables. His sparse pointed beard, quaintly worn as seen on engravings of ancient tribal kings, is matched in distinction by the fresh white carnation in his lapel beside a rosette of some Order.

It is evident that Summers’ daughter will be the one to speak.

His face changes as he listens to her story. It’s as if he has been returned by her to another life: this is the withdrawn and acutely attentive face of Senior Counsel, not the affable deputy chairman or whatever-he-is in the headquarters of this banking conglomerate or whatever-it-is. The girl’s story becomes a confession in all the detail she has learned carefully by rote and, it’s obvious from her wary delivery, she’s aware her companion is silently monitoring.

In that other expression of his powers of intellect, of professional mastery, the lawyer has heard and analysed countless confessions while they were in progress. He alternates concentration on her words with unapologetic examining glances resting on the companion — yes, to verify, in his own interpretation of what he is hearing, the likely actions and motivations of this lover.

When she ends — or rather stops speaking — she has to control rising emotion, she wants to go on, to plead, to state her case, her lover’s case; the lawyer is familiar with the symptoms in many bearing witness over the years in court. He sits back in his chair and presses his shoulders against the cushioned rest, invisible robes are adjusted round them— Senior Counsel was an Acting Judge for a period, and could be permanently His Honour Mr Justice Motsamai on the bench of the High Court now if he had not decided for that other, more profitable form of power over human destiny, financial institutions. He is also only too well accustomed, from his past career, to the gaze that waits upon him as an oracle. It is one of the rewards of having doffed those heavily-goffered robes in exchange for a custom-tailor’s cut of light-weight suit that he doesn’t have to be the object of that sort of expectation any more; he himself sometimes had had to fight emotion in knowing, vulnerable man he was himself, black man whose old parents had been supplicants themselves, that nothing more oracular than management of dry facts would come from him.

He let his moments of silence tell them this, these two.

Then he spoke. — You are not married.—

— No. Oh no.—

There comes from him a kind of organ note, something between an exclamation and a groan — an old African affirmation. It could be a comforting or a warning — she is at home with the particular non-verbal expressions that are natural to Africans as Greeks or Italians or Jews have their characteristic ones, but her familiars are the young who have lost the more grandiose, eloquent, traditional African resources in self-expression, and have passed on easily to The Table, the bars, the streets, only those adapted to general usage, across all local cultures, heard all over coming from those of their generation, all colours and kinds.

Читать дальше