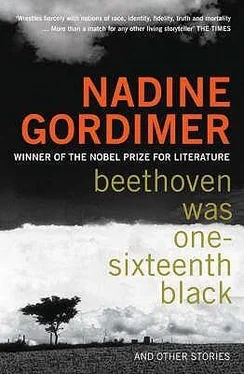

Nadine Gordimer - Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2007, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She went to every performance in which he was billed in the cast. A seat in the middle of the second row, the first would be too obvious.

If she was something other than a groupie, she was among the knot of autograph seekers, one night, who hung about the foyer hoping he might leave the theatre that way. He did appear making for the bar with the theatre director and for a moment under the arrest of programmes thrust at him happened to encounter her eyes as she stood back from his fans — a smile of self-deprecating amusement meant for anybody in the line of vision, but that one was she.

The lift of his face, his walk, his repertoire of gestures, the oddities of lapses in character-cast expression on stage that she secretly recognised as himself appearing, became almost familiar to her. As if she somehow knew him and these intimacies knew her. Signals. If invented, they were very like conviction. The more she ignored it: kept on going to take her place in the second row. At the box office there was the routine question, D’you have a season ticket? Suppose that was to have been bought when the Rendall Harris engagement was announced.

She thought to herself, a letter. Owed it to him for the impression his roles made upon her. His command of the drama of living , the excitement of being there with him. With the fourth or fifth version up in her mind, the next was written. Mailed to the theatre it most likely was glanced through in his dressing room or back at his hotel among other ‘tributes’ and either would be forgotten or might be taken back to London for his collection of the memorabilia boxes it seems actors needed. But with him, there was that wry sideways tilt to the photographed mouth.

Of course she neither expected nor had any acknowledgement.

After a performance one night she bumped into some old friends of Laila’s, actors who had come to the memorial gathering, and they insisted on her joining them in the bar. When Rendall Harris’s unmistakable head appeared through the late crowd, they created a swift current past backs to embrace him, draw him with their buddie the theatre director to room made at the table where she had been left among the bottles and glasses. For her this was — he had to be taken as an exchange of bar-table greetings; the friends, in the excitement of having Rendall Harris among themselves forgot to introduce her as Laila’s daughter, Laila who’d played Corday in that early production where’d he’d been Marat; perhaps they have forgotten Laila, best thing with the dead if you want to get on with your life and ignore the hazards, like that killer taxi, around you. Her letter was no more present than the other one under the volumes of plays. A fresh acquaintance, just the meeting of a nobody with the famous. Not entirely, even from the famous actor’s side. As the talk lobbed back and forth, sitting almost opposite her the man thought it friendly, from his special level of presence, to toss something to a young woman no-one was including, and easily found what came to mind: ‘Aren’t you the one who’s been sitting bang in the middle of the second row, several times lately?’ And then they joined in laughter, a double confession, hers of absorbed concentration on him, his of being aware of it or at least becoming so at the sight, here, of someone out there whose attention had caught him. He asked across the voices of others which plays in the repertoire she’s enjoyed best, what criticisms she had of those she didn’t think much of. He named a number she hadn’t seen; her response made clear another confession — she’d seen only those in which he played a part. When the party broke up and all were meandering their way, with stops and starts in back-chat and laughter, to the foyer, a shift in progress brought gesturing Rendall Harris’s back right in front of her — he turned swiftly, lithely as a young man and, must have been impulse in one accustomed to be natural, charming in spite of professional guard, spoke as if he had been thinking of it: ‘You’ve missed a lot, you know, so flattering for me, avoiding the other plays. Come some night, or there’s a Sunday afternoon performance of a Wole Soyinka you ought to see. We’ll have a bite in the restaurant before I take you to your favourite seat. I’m particularly interested in audience reaction to the big chances I’ve taken directing this play.’

Rendall Harris sits beside her through the performance, now and then with the authority to whisper some comment, drawing her attention to this and that. She’s told him, over lasagne at lunch, that she’s an actuary, that creature of calculation, couldn’t be further from qualification to judge the art of actors’ interpretation or that of a director. ‘You know that’s not true.’ Said with serious inattention. Tempting to accept that he senses something in her blood, sensibility. From her mother. It is or is not the moment to tell him she is Laila’s daughter, although she carries Laila’s husband’s name, Laila was not known by.

Now what sort of a conundrum is that supposed to be? She was produced by what was that long term, parthenogenesis, she just growed, like Topsy? You know that’s not true.

He arranged for her seat as his guest for the rest of the repertoire in which he was playing the lead. It was taken for granted she’d come backstage afterwards. Sometimes he included her in other cast gatherings ‘among people your own age’ obliquely acknowledging his own, old enough to be her father. Cool. He apparently had no children, adult or otherwise, didn’t mention any. Was he gay? Now? Does a man change sexual preference, or literally embrace both. As he played so startlingly, electric with the voltage of life the beings created only in words by Shakespeare, Strindberg, Brecht, Beckett — oh you name them from the volumes holding down the letter telling of that Saturday. ‘You seem to understand what I — we — actors absolutely risk, kill themselves, trying to reach the ultimate identity in what’s known as a character, beating ourselves down to let the creation take over. Haven’t you ever wanted to have a go, yourself? Thought about acting?’ She told: ‘I know an actuary is the absolute antithesis of all that. I don’t have the talent.’ He didn’t make some comforting effort. Didn’t encourage magnanimously, why not have a go. ‘Maybe you’re right. Nothing like the failure of an actor. It isn’t like many other kinds of failure, it doesn’t just happen inside you, it happens before an audience. Better be yourself. You’re a very interesting young woman, depths there, I don’t know if you know it — but I think you do.’

Like every sexually attractive young woman she was experienced in the mostly pathetic drive ageing men have towards them. Some of the men are themselves attractive either because they have somehow kept the promise of vigour, mouths with their own teeth, tight muscular buttocks in their jeans, no jowls, fine eyes that have seen much to impart, or because they’re well-known, distinguished, well yes, even rich. This actor whose enduring male beauty is an attribute of his talent, he is probably more desirable than when he was a novice Marat in Peter Weiss’s play; all the roles he has taken, he’s emerged from the risk with a strongly endowed identity. Although there is no apparent reason why he should not be making the usual play towards this young woman, there’s no sign that he is doing so. She knows the moves; they are not being made.

The attention is something else. Between them. Is this a question or a fact? They wouldn’t know, would they. The other, simple thing is he welcomes her like a breeze come in with this season abroad, in his old home town; seems to refresh him. Famous people have protégés; even if it’s that he takes, as the customary part of his multiply responsive public reception. He’s remarked, sure to be indulged, he wants to go back to an adventure, a part of the country he’d been thrilled by as a child, wants to climb there where there were great spiky plants with red candelabras — it was the wrong season, these wouldn’t be in bloom in this, his kind of season, but she’d drive him there; he took up the shy offer at once and left the cast without him for two days when the plays were not those in which he had his lead. They slipped and scrambled up the peaks he remembered and at the lodge in the evening he was recognised, took this inevitably, autographed bits of paper and quipped privately with her that he was mistaken by some for a pop star he hadn’t heard of but ought to have. His unconscious vitality invigorated people around him wherever he was. No wonder he was such an innovative director; the critics wrote that classic plays, even the standbys of Greek drama, were re-imagined as if this was the way they were meant to be and never had been before. It wasn’t in his shadow, she was: in his light. As if she were re-imagined by herself. He was wittily critical at other people’s expense and so with him she was freed to think — say — what she realised she found ponderous in those she worked with, the predictability among her set of friends she usually tolerated without stirring them up. Not that she saw much of friends at present. She was part of the cast of the backstage scene. A recruit to the family of actors in the coffee shop at lunch, privy to their gossip, their bantering with the actor-director who drew so much from them, roused their eager talent. The regular Charlie dinners with her father, often postponed, were subdued, he caught this from her; there wasn’t much for them to talk about. Unless she were to want to show off her new associations.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.