She finds it funny that this time she’s the one helping me to my feet.

Yep, we’re both inostrantsi.

And colleagues besides.

This is Black Hill, Ula says. They built it to cover up the burial site. It’s actually a huge knoll.

I nod.

She’s glad to see me! Apart from that, she doesn’t see anything cheerful about our situation.

Ula’s in a grim mood. But I’m actually happy.

She isn’t fat. She’s big, hefty. Much taller than Maruška. Wrinkles on her face and forehead. I thought maybe she was just tired, but she’s a bit on the old side. Fair hair, darker than Sara’s. It actually looks nice with the yellow coveralls.

I’m glad I found her, that’s for sure.

We lie in a frayed tent on our bellies, heads poking out. A stretch of the plain shines white through the trees. I don’t look over there. For a while it doesn’t rain or snow, which is very rare, Ula explains. A tin pot of water heats up on the fire. There’s a stream nearby, she says. Nothing to eat.

Some guys with a fire about ten metres away are stuffing their faces with bacon. Bread. I recognize the bearded guy I ran into in the forest. Sitting there with his pal. The two of them look almost alike.

Fyodor and Yegor, Ula says. They broke the GPS, idiots!

She hates them. They belong to a group of partisans that the Ministry of Tourism assigned to her expedition.

Our trip was supposed to end in Khatyn, she says. That’s where we were supposed to bring the samples. But those bastards said they saw a fire and wouldn’t go any farther. So we stayed here.

The other attachés, as the Ministry called the partisans, had long since run away. Took what they could, destroyed the rest.

According to Ula, they’d been sabotaging her work ever since the political situation stabilized. Apparently the opposition was really taking a beating.

I tell her about myself. After trudging around on the plain, I’m in seventh heaven now, tucked cosily in a sleeping bag and safe inside a tent. I tell her about my foreign expertise, my trip to this country. And the fire at the museum. Not everything, just some of it.

The partisans weren’t lying, I say. Khatyn is gone now!

I don’t mention Alex and Maruška.

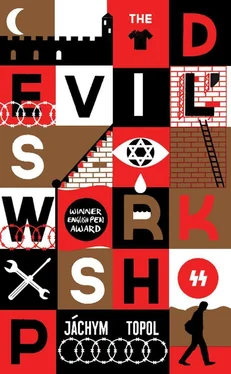

Yes, of course, Ula says. The Devil’s Workshop, that’s why I’m here too.

She shows me the samples. The ones that didn’t fall in the snow or get lost along the way. She had twice, no, three times as many!

She’s an egghead, a researcher and a field worker.

The best in her field!

That’s why they chose her out of everyone else in Berlin.

But now it’s over.

I turn around. Squint into the gloom of the tent to where she’s pointing. Crates, boxes. But not old-fashioned ones like Kagan had, all battered and made of wood. These are smart plastic things. Double-sealed lids. Blue, red, yellow — almost too much for my eyes to take.

Imported, huh?

Mm-hm.

All of her boxes and plastic bags, with bones and rags in various stages of decay, are stored at the back of the tent. Behind our backs, piled up in a wall. A wall against the wind.

And I can take as many blankets and sleeping bags as I want.

They’re left over from her colleagues and co-workers.

We bundle up and wait till the water’s ready for tea.

Talk back and forth in our languages.

I guess I fell asleep first.

I open my eyes, feel it, can’t see. Ula’s holding my hand. We’re warm. I hear a horse snorting. Didn’t get up to look, though. I’ll fix things in the morning, I promise myself. In the night I hear a scraping, probably the horse rubbing against a branch, clicking its hoof against a stone.

In the morning the two men are gone. Along with the horse. Ula sits outside the tent, a loaf of bread in her hand. They must have left it for her. She scrambles into the back of the tent, by the samples, crawls under a pile of blankets and stays there.

I go to check out the camp. We’re hidden from the wind by a gorge, a small, narrow ravine carved into the hillside.

I go on through the trees. There are crosses all over the place. And those stones with writing on them. I find the wagon right away. The horse was standing right here, to judge from the tracks. Maybe they both rode it. If I went down to the foot of the hill, I’d be able to see their tracks stretching away across the plain.

There are more boxes under the tarpaulin on the wooden wagon. I open the one closest to me, a red one, little by little, but there are no tsantsas, only skulls. One has a bullet hole in the forehead so big you could stick your finger through it. I give the skull a rap with my knuckles and put it back.

No supplies, no weapons, no clothing, nothing in the wagon but samples. We’ll leave it here, I say to myself. Screw the samples. Let ’em rot. We’re getting out of here. We’ll make it to some road or other. We’ll be together. That’s what I thought. But then the purga hit.

The next thing I know there are leaves and twigs flying at me, the trees shake and groan in the wind, the snow whips in off the plain, suddenly it gets hard to breathe, the air in my lungs begins to hurt, a six-foot branch tears loose and goes sailing over my head. I crawl back inside the tent.

There’s a storm, I say. Ula sits, leaning against the boxes.

It’s a purga, she says. We won’t get out of here now. I’ve got two buckets of water.

The ravine protected the tent. Still, I almost couldn’t poke my head out. The wind instantly glued my mouth shut, my eyelids together. I couldn’t even stand up outside. The wagon would’ve been blown to pieces. I imagined the broken crates, bones flying through the air, skulls smashing to bits on the rocks.

So, Ula. You’re the expert. How long will it last?

The last time a blizzard hit, she said, she was locked up for eight days. With a bunch of co-workers, food and drink, inside a cabin. They even had a guitar and board games. They were collecting samples in Siberia at the time. Soon it’ll start to snow, and once the blizzard’s over, then come the frosts. Unless somebody turns up, we don’t have much of a chance, Ula says.

At night, or whenever we think it’s night, we sleep. Squeezed together. We wake up. Eat some bread.

I have a dream about the Spider. It’s inside me. Melting. Poisoning me. All the data and contacts spill into my guts.

She’s sitting next to me with her eyes open.

She tells me about her work.

Her team was selected for reconnaissance of burial sites in one of the regions of Belarus that was severely affected by radiation.

When Chernobyl blew up, the fallout contaminated a third of Belarus, she said. Radiation genocide, they call it. They trudged around the graves all day in hot weather and pouring rain. The locals from the village were ready to spit on them. They all knew where the skeletons were, but it was taboo. They said, When you dig up an old grave, you break the ribs of the living.

The mayor of one of the villages said, Why are you digging there? Leave them alone. Us too. Their things went missing at night. They spent hours excavating an area only to have somebody come and fill it all back in. They suspected the village youths. One day Ula went shopping in town and had to convince the crowd that gathered around her that she was Dutch. Not German. Meanwhile the victims had obviously been shot by the NKVD.

How do you know?

From the bullets. And other details.

Did you know that to this day the cancer rate for children in contaminated areas is still twenty times higher than anywhere else in Europe? They have to import their food.

Ula, that’s awful!

Her co-workers dropped out one by one. Work injuries, diarrhoea from bad water. Depression. And then the problems started with the workers from the ministry. A lot of samples were going missing.

Читать дальше