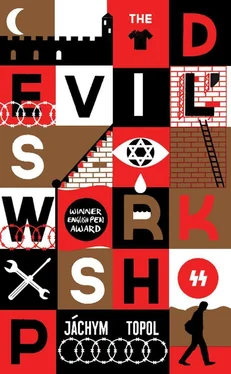

Jáchym Topol

Devil's Workshop

on a river of emotion

on a hillside without emotion

a tin sun

founds

a colony of terror

Pavel Zajíček

Look, I’ve got someone else’s scars, how did they get there?

Dorota Masłowska

I’m on the run to the airport in Prague. Run, well, more like I’m walking along the roadside ditch, wrapped in a dizzying cloud, from my drinking.

I’ve been drinking a lot lately.

Now I’m walking along the highway. Every now and then I get down in the ditch and crawl so the cops won’t be able to spot me from their patrol car.

So they won’t catch me and ask me about the fire in Terezín.

Sometimes I throw myself down in the ditch, wedge myself in with my back pressed up against the dirt, and just stay there like that.

Little by little, I’m making my way to the airport in Prague.

There’s still some of Sara’s wine left in the bottle. I ate all the meat that they gave me.

At first I didn’t want to, but eventually I forced it down. I need the energy.

The moon’s almost full now.

The redbrick walls of Terezín are far behind me, the walls of my hometown.

The town that, as my dad used to say, was founded by the Empress Maria Theresa, since whose reign hundreds of thousands of soldiers from many an army have passed through its gates. The Empress Maria Theresa was fond of military parades, said my dad, a major of military music who loved the Terezín parades and their marching bands.

I’m walking along with my back to the town, all those enormous eighteenth-century buildings far behind me — storehouses for millions of bullets, stables for hundreds of horses, barracks for tens of thousands of men. I left, like all the defenders of the town left before me. The influx of soldiers to this town created for soldiers had come to a halt.

And, without an army, the town was falling apart.

They sold my goats, who used to graze on the grass inside the fortress walls.

Most of them.

My dad didn’t live to see it.

I’m one of the few who wanted to save Terezín.

My mum said she and my dad weren’t expecting it when I came into the world. She also used to say that it would’ve been just the most beautiful thing if I had stayed so tiny I could’ve hidden inside a thimble. I could’ve lived on peas, fought over drops of milk with the cat, and walked around wrapped in a little rag of cloth, her very own Tom Thumb.

At first it delighted me, how could it not?

But there was no avoiding it: I grew up the same as everyone else.

I no longer rejoiced when my dad went off to work with his baton in a red case painted with a yellow hammer and sickle and my mum sealed the windows and doors with pillows and blankets.

When I was very young, I’m told, I used to clap my little hands when my mum pushed the furniture away from the walls.

In the middle of all the cabinets and chests, the cupboards, overturned chairs, armchairs and the fancy divan, she created a safe hiding place, a nest for just the two of us.

I was overjoyed when my mum and I would huddle up close in our warm nest and hold each other till my dad came home and dragged us out of our safe place.

The world outside was huge and my mum refused to set foot in it.

As soon as I could, I started running away from her.

I’m not really sure how it happened, but one day I wrenched myself out of her grip, unwound myself from her sweet embrace, pushed away her outstretched arms, crawled under the divan, climbed over the armchair, tugged at the door handle, opened the door, and scooted out.

I joined the other kids, racing back and forth along the ramparts, falling down in the grass like we’d lost our senses, and getting back up and doing it all over again.

And Lebo! Everybody knew him, there was no way not to in Terezín.

Then there was also that business with my mum.

Lebo was her only friend. Oh, not like that, but he brought her flowers.

The aunts also took care of my mum.

She wouldn’t even leave our flat.

But whenever Women’s Day rolled around, or the anniversary of our liberation by the Soviet army, she could always count on Lebo to give her a huge bouquet of flowers he had picked under the ramparts, out of reach of my greedy goats. Even on Mother’s Day, which wasn’t celebrated under communism, he would secretly hand her a bouquet dusted with red from the town’s walls. Uncle Lebo always made sure to give my mum a bouquet.

Supposedly there was once a time when he and my mum actually talked, but I don’t remember it.

What I do remember is that she hardly spoke in the end.

All she ever wanted to do any more was curl into a ball and take up the smallest possible space, searching for a spot just big enough to take a breath, that was all she needed.

All of the kids in Terezín knew Uncle Lebo.

We used to think that he was called Lebo because of his long skull, which didn’t have a single hair poking out of it. We just assumed his real name was Lebka, which is Czech for skull , but Aunt Fridrich explained to me that when she was a girl in the concentration camp here during the war, she had hidden the newborn Lebo in a shoebox under her bunk, safely off in a corner of the room for condemned women and girls, and the way it was with his name, she said, was the bunkroom elder was a Slovak, and a midwife, as luck would have it, and when she delivered the baby she said, out loud but in a whisper, what everybody in the room was already thinking: Bude potichu, alebo ho udusíme — Either he’s quiet or we’ll suffocate him — and that Slovak word lebo became his name.

Giving birth and hiding a baby in the bunkroom wasn’t allowed, but the women hoped the Red Army was making its way to Terezín, and they turned out to be right.

None of my aunts, including Aunt Fridrich, was actually at the birth itself. It was overseen by older, experienced women, who are all dead now. If only my aunts hadn’t been so young, they could’ve told me who Lebo’s mum was, but who cares! The girl who had Lebo probably lost her life during the war. Maybe she went off on one of the last transports to the East, or maybe, like my aunts said, she met her end in a typhus grave. If she’d been caught giving birth illegally, it would’ve meant a bullet for her anyway, Aunt Fridrich explained.

But none of us took precautions! she said as she sat there reminiscing about the old days in Terezín, her gaze sliding along the walls of her tiny flat. Then the sound of suppressed laughter came bubbling up from her throat, until she burst out laughing, and Aunt Holopírek and Aunt Dohnal, who had also spent their youth in Terezín, laughed right along.

Lebo was our uncle, he was uncle to all the little tots in Terezín.

It was for him we combed the tunnels. Being small, we could fit into every sewer and drain, where the build-up of fence boards, washed out of the meadows by floods, sometimes made the water bulge in strange ways. Nothing rotted underground. The warning signs posted by the Monument staff were a joke, even a child’s hand could push them out of the way, and the bunkers in the outermost bastions had an irresistible charm.

It was great finding a hollow pipe, or an old cowshed just for yourself, a parapet out on the ramparts where nobody went much, with bottles and condoms lying around, and squeezing right into the corner, feeling the edges and curves of the walls.

My mum didn’t even want to let me go outside.

You should’ve stayed inside me, she used to say. What were you missing? She herself didn’t go out at all.

Crazy lady.

That’s the kind of thing my aunts, the old ladies from the neighbourhood, would say — Aunt Fridrich, Aunt Dohnal, Aunt Holopírek and the rest — when they got together and gabbed about my mother: It’s because of what happened! It isn’t her fault! She suffered like an animal!

Читать дальше