From the tall roof MAAR announced urbi et orbi its glittering standard of living. Its mighty acoustics had all but drowned out a blind peddler’s feeble supplication issuing from a dark doorway, “Shoelaces, black, yellow — two dinars; ten envelopes, letter paper inside — six dinars …” The blind man’s monotonous litany sounded tired and unconvinced; the pathetic bit of verbal advertising aspired only to mask the begging, that much and no more.

Melkior took refuge in the doorway with the blind man and fell to watching: what can this MAAR thing hope to accomplish? The viewer stands entranced with his head thrown back and drinks in, henlike, the filmed comfort of well-being. From his earthbound condition he watches MAAR’s looming mirage, listening to this voice “from the other world” and is already intoxicated by the luxurious illusion of his eternal longing to be pampered — and then there comes the voice of the accursed petty things — the shoelaces, black, yellow, for two dinars … and he fingers his two dinars in his pocket and his petty need for shoelaces, black or yellow as the case may be. Tungsram-Crypton’s glare has dimmed … and what do I need the Flit grenadier for … and I see this business with Napoleon is just a ruse. … The evening has gone down the drain. To think that he was actually willing to die for the sake of First Croatian! Can’t they have blind people weaving baskets or something instead of letting them beg like this? Melkior felt the thought himself, through irritation with the beggar’s plea. Why indeed can’t they open a center with heating provided, for the poor blind people to gather, think of the savings on electrical lighting … he made to redress his cruel thought, even bought a pair of yellow shoelaces (although he needed black) and generally cast about for a way to help the blind man. … He dropped a silver piece on the ground, picked it up again, and asked him, “You lost this coin, didn’t you?” “Could be, I’ve got a hole in my pocket,” replied the blind man half-jokingly, just in case, but he did, eagerly, accept the coin.

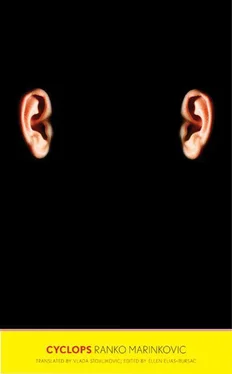

The quaint act of charity moved a person nearby. A clerical collar around his neck, the man had cast only a passing, sadly indifferent glance up at MAAR’s magic tricks as he squeezed through the throng. Then his spirits soared with a “true glow” when Melkior found a way (and how Christian a way!) of being charitable to the blind man. “When giving alms, no need to make a show of it.” He patted Melkior on the shoulder and, giving him an approving smile, dipped into the crowd again. Melkior only managed to catch a glimpse of his head, wrinkled, sad, wrung between the hands of some terrible misfortune, and a pair of large ears thereupon, jutting grimly out on either side. He was astounded by how oddly large they were, so similar to a very familiar and well-remembered pair. … But back in those days the head had been ruddy and full, young and terrifying, with those selfsame batwing ears amid waves of thick hair which protected them from ridicule.

“That pale scrawny neck!” cried Melkior in a low voice, “is it possible?”

After him, then! He had to see those ears again!

But who is to know whether or not ears have a hiding place for their memories? A secret spring-catch drawer from which at night, when they burrow into solitude, they take out trinkets to caress and sob over?

Melkior launched into a romantic tale about the mysterious soul of a priest roaming through the urban hustle and bustle seeking peace and salvation. … But the romantic tale is something else. … Those ears carry with them a different secret, one that darkened his entire childhood. He still wears the catechistic slaps, riddlelike, on his cheeks. And all that subsequently befell Dom Kuzma was cobbled together by his imagination into a story of a man apart. He was even ready to proclaim Dom Kuzma a martyr, for all that the martyr had whacked a pair of red-hot slaps on his darling cheeks. (The older ladies used to say at the time how “that child” had such darling cheeks — and they would kiss him, even nibble at his cheeks, the old maids.)

All the pupils in Melkior’s school, including the tiny first-graders who didn’t even know how to write an i , knew how to draw an ear. They all, everywhere and at every opportunity, drew ears. Ears on the blackboard, on the classroom desktop, on the floor, on the roadbed, on fences, on walls, on any wall near which they happened to have a piece of charcoal handy. All the books, the notebooks, were doodled over with ears. Ears on agave leaves, on the beach sand. There sprang into being a secret sect of otosists, aurists, ear maniacs, in hoc signo vinces. Ears everywhere, like early-Christian fish. A large, huge, outsize ear on any potatolike head. The head did not matter, what mattered was the ear … to draw it as well as possible. To master the technique and the cliché. The older lads did the Charleston in trendy bell-bottomed trousers; the small boys drew ears fanatically. They did not know why it had to be the ear. Their parents, their teachers, asked, “Why ears?” “Everyone is drawing them,” the child would reply, puzzled that this, too, should be forbidden. “An epidemic,” people shrugged, “the measles.” And the local gendarmerie post received a telegram from higher up: had the phenomenon anything to do with the Communists?

The silly puerile manias. Collecting stamps was all right — adults did it, too, philatelists, postal-oriented thinkers. But carob beans! — that was for seminarians (the independent faction). Melkior had kilos of the things. He threw the lot away when sock knitting caught on. The socks naturally never reached the length of the heel; the boys were ignorant of either the utility or the futility of work.

The ear-drawing was an outburst and it spread like the plague. Later on, measures were taken (by the educational authorities), but they served only to fan the epidemic: they helped to reveal the meaning of The Ear … which previously no one might have divined.

When he learned the reason Melkior thought it seriously insulting and undignified, and he never drew an ear again. But Dom Kuzma’s hand eventually reached him nevertheless. After the physical pain subsided he felt ashamed before the catechist, he claimed his part of the guilt. Shame made him stop going to school, lest he meet Dom Kuzma again. Which he did not … until tonight. (But in such pathetic shape!)

Dom Kuzma brought too much passion to his struggle to prevail. What he did was senseless, even mad; he seemed to want to wipe all those provocative “ears” around him with his bare hands (or, slaps). He went in for mindless collective face slapping in his classes, for purely preventive reasons. His vengeful fervor, brandishing a heavy hand, reached everywhere, like God’s punishment.

Vengefully, he gave every pupil a zoological nickname. Or two, in tandem. He used the names of curious animals so that he could ridicule a person, to provoke laughter. … But there was no laughter, only the low cunning of children: how to weather the blows.

Dom Kuzma spied a bumpkin sitting at his desk and, wiping his avian nose on his sleeve, the thatch of his hair overgrowing his neck and (remarkably large) ears:

“What is hope? … you there, Andean Condor!”

The ornithological individual felt the two bright swords of Dom Kuzma’s gaze on his avian countenance and promptly identified with that large predatory bird of the Andes.

“Ho- … hope is … hope is when …”

“Come here, I’ll whisper it … in your ear.”

The Condor approached the lectern, hand on ear (as though unsure of his hearing), but Dom Kuzma smacked him on the other ear with his meaty hand. A boy with a funny nose, which gave him a permanent grin, instinctively flinched at the blow to the Condor’s ear. That is why Dom Kuzma chose him:

Читать дальше