“Where are you living?” Pronek asked.

“Where do I live? No woman in this lovely city would tell a complete stranger where she lives. Don’t ask a single woman that question.”

“I am sorry,” Pronek said, looked down and fell another half step behind.

“But you’re a stranger no longer. I live in Uptown. Where do you live?”

“Rogers Park.”

They crossed Halsted. A policewoman, her chest encrusted with Kevlar, was frisking a man facing the wall, his left hand up, his right one gripping a walking stick. In the window of Zorba’s they saw a gyros chunk like a misshaped planet, slowly revolving.

“When did you come here?” Rachel asked.

“Nineteen ninety-two, just before the war.”

“Is your family there?”

“Yes.”

“Are they all right?”

“They are old.”

“You watch it on TV and feel nothing but numb helplessness. It just makes me angry.”

“I know.”

“It must have been hard for you.”

Pronek nodded, but he didn’t want her to pity him, yet he liked that she paid attention to him. She talked to him over her shoulder, her head twisted, and Pronek imagined her turning into a pillar of salt.

—

They took the same train. It sped underground, producing apocalyptic, isolating noise, as if everything above ground had just collapsed. Rachel was in the seat in front of him, next to a black woman grasping a tiny Bible in her hand, breathing heavily and mumbling between the breaths. The only words he could make out were “weeping for her children.” Rachel scratched her neck, her index finger coming down from her right ear toward the collar, leaving ruddy curves.

Pronek lay supine in the darkness, pressing his eyelids tight together, determined to force himself to sleep, feeling tension in his facial muscles, as if his face were ossifying. The man was screaming: “You ain’t gonna get me, motherfuckers!” A train rattled by and Pronek felt anger rising in him — he wanted silence, no crazies bellowing, no trains screeching, no sirens warbling maniacally. His kneecaps were sweaty and sticky — he turned sideways and put the blanket between them. He imagined walking Rachel home — strolling down her linden-tree-lined street, rich scents in the air, then sitting on her stairs and talking, then going upstairs and making love.

“You ain’t gonna get me, motherfuckers!”

Pronek jumped from bed, his hands curling into painful fists, and looked out: a preppy-white businessman in an orderly dark suit, holding a briefcase close to his chest, was stomping his feet, pointing his finger toward the sky every now and then. Pronek’s tension transformed into a clean, simple hatred of the man. He opened the window and glared at the man as if his hateful fury could be carried through the ether of the city.

“You ain’t gonna get me! Fuck no! I don’t fucking think so!”

Pronek wanted to think up a killer sentence, something that would make the man shut up instantly and think about his behavior. He juggled the words in his head, stressing them differently, inserting and re-inserting necessary curses, ascertaining the voice-power necessary to crush the man’s demented will. He huffed and puffed and finally, with the anger stuck in his throat, he opened his mouth and hesitantly shouted:

“That is not polite!”

The man stopped hollering, shook his head as if he had received a punch, and stood petrified for a moment. Then he slowly looked up at Pronek, pointed his finger at him, and thundered:

“And you ain’t never going to get me, because the Lord is with me, in all his might!”

Pronek retracted inside and stood near the window, afraid to move or look outside, the darkness throbbing around him, his knees giving way.

“Just be relaxed and look them in the eye,” Rachel said.

Pronek knocked on the door, once, then twice, although there was a buzzer in clear sight. A gaggle of croquet mallets was leaning on the fence and a family of wooden raccoons huddled on the porch. Pronek closed his eyes, because when he closed his eyes, there was an instant of hope that he was dreaming all this and that it would all vanish when he looked out again. The door opened and Pronek opened his eyes and there was a woman wearing sunglasses, her dark hair coiled up, wearing an oversized Hawaiian shirt, her face pallid, as if she were a vampire.

“Hello,” Pronek said. “I am Joseph and I am from Greenpeace. We like to talk to you.”

The woman said nothing.

“And this is Rachel. From Greenpeace too.”

It was unnerving not to know where the woman was looking. Perhaps she was blind.

“How are you?”

“I’m just dandy peachy,” the woman said, her voice coarse. “What can I do for you?”

Pronek wanted to look at Rachel to get a signal of approval, he didn’t know whether he was doing it right. But he didn’t dare take his eyes off the woman’s face, as if she should disappear if he did.

“We like to talk to you about envir— enviro —environment. Maybe you can help us.”

“Where are you from?”

She opened the door wider. Pronek could see the TV — a pair of hands was building something in silence.

“From Greenpeace.”

“No, what country are you from?”

Above a gas fireplace with flimsy flames flickering, there was a portrait of an Indian in profile with a huge feather, sunset orange the dominant color.

“I am from Bosnia.”

“Bosnia is far away,” the woman said, slurring the words. “But I like your accent.”

“Thank you.”

“So what can I do for you?”

“We like to talk to you?”

She pointed at Rachel: “Is this your girlfriend?”

“No. I don’t know. No.”

“Ma’am, we come out here to talk to you,” Rachel said, “and ask for your support.”

“You got my support.”

“Financial support.”

“Hey, I can give you a drink or a massage, but dough — no! I am a single woman.”

“Thank you, ma’am. Sorry to bother you.”

“Thank you. Sorry,” Pronek echoed.

“Come back any time,” the woman said, and stepped out on the porch, as they were walking down the driveway. “Any time.”

“One day,” Rachel said, “I am going to bring my camera and take pictures of these people. They are unbelievable.”

“I like them,” Pronek said.

“Okay, advice: don’t let them suck you into babbling. There are a lot of lonely people out here, you know, housewives, senior citizens, perverts, unemployed fratboys. They got nothing to do all day long.”

“It is hard. My English is bad.”

“Just be relaxed. If you speak English with an accent, you speak at least two languages and that is twice as many as the people in this godforsaken place. People who like you will give you money, and people who don’t won’t.”

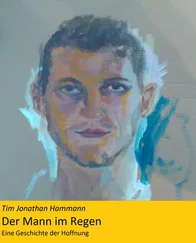

It started raining again, reactivating the puddles on the street, raindrops shattering their surface.

“You know,” Pronek said wistfully, “I think that everywhere there is the home, you have the puddle where you see when it rains.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean you look through the window when you don’t know if is it raining and you have your puddle where you can see the rain.”

“Yeah, I see. That’s nice.”

“I had one in Sarajevo, in front of my home.”

“I like that,” Rachel said.

“Hello,” Pronek said, “my name is Jozef and I am from Greenpeace. Do you care about the dolphins?”

The old man was sitting on the porch wrapped in a checkered blanket, with earmuffs pressing on his temples and wool-mittened hands gently deposited in his lap.

“Nope,” he said. “I couldn’t care less.”

His face was splattered with dun dead-skin blotches.

Читать дальше