The jukebox was turned off and a band called the Soviets started to test their equipment, saxophone erupting in blurts and squiggles, cymbals crashing down over the room. Giddle and Burdmoore retreated to a dark booth where they seemed to be working out some ancient connection, never mind that Giddle had possibly mistaken Burdmoore for someone else.

We were at the bar having one last drink. Sandro and I had meant to leave but he and Ronnie got involved in a semi-argument. Ronnie brought up Italy. He said I should go to Monza and that Sandro shouldn’t be a stick-in-the-mud about it. “You’re against it,” he said to Sandro. “I get it. It’s your family. But the thing is, she’s the fastest chick in the world, Sandro. And you’re slowing her down.” He said it lightly, teasingly, drunkenly, and Sandro went sullen.

“Thanks, Ronnie,” Sandro said. “I spend my whole life trying to get away from Valera, and I end up with their spokespersons, my best friend and my woman, both against me. Why don’t the two of you sell me a set of tires while you’re at it?”

I felt bad. But I wanted to go to Italy and hadn’t possessed the courage to push for it. Ronnie was doing it for me.

But why? I wondered. For what motivation? And then I realized he was convincing Sandro that Sandro and I should leave New York, and I thought, won’t you miss me, Ronnie?

At the confusion of that, I assented to the next round of drinks, while Sandro and I argued about Valera and Italy. “Why can’t you just do something here? Focus on the photographs you have,” he said. “Of Bonneville.”

I wanted to carry the project through, I said. Going to Monza was part of Bonneville; it was one project.

Ronnie ended up in a nearby booth with Talia and the two less-pretty accomplices. My discussion with Sandro was put on hold as we watched them. The girls had gotten the idea to slap and hit themselves, with Ronnie’s encouragement. They were laughing, going around the table, each girl slapping herself. The first round of slaps was light, a light pat on the cheek, the heel of a hand on the forehead. Each of the girls slapped herself, and with each slap they all erupted in laughter. When it was Talia Valera’s turn, she punched herself in the face with a closed fist. She had especially large fists, like a puppy with huge paws.

Sandro went over to the booth and tried to reason with her.

“Calm down, Sandro,” she said. “It’s just a game.”

“You’ll end up with a black eye,” Sandro said.

She didn’t care. Ronnie had his camera and took pictures. She gazed at the lens in a frank manner.

I thought again of the girl on Ronnie’s layaway plan. Had she taken a bath and given up, gone to sleep? Or put on more lipstick, gone out looking for Ronnie, but to the wrong places?

Flash. Talia posed again for the camera. Her eye was swollen now, and had the taut appearance of polished fruit. There was a gash above her eyebrow, probably from the silver rings she wore, plain metal bands that shone prettily against her tanned skin. I detected pride in her look, as if she felt that the gash and swollen eye were revealing her inner essence, deep and profound, for Ronnie and his camera.

“This is great,” Ronnie said. Click-click. Flash. “Just great.”

* * *

“He refuses to grow up,” Sandro said to me as we were leaving.

But was that what he refused to do, or was it something else?

Either way, while Ronnie acted like an asshole and got away with it, Sandro and I were on the street getting mugged.

In the rain. In a squat. In an orgy. We meet again.

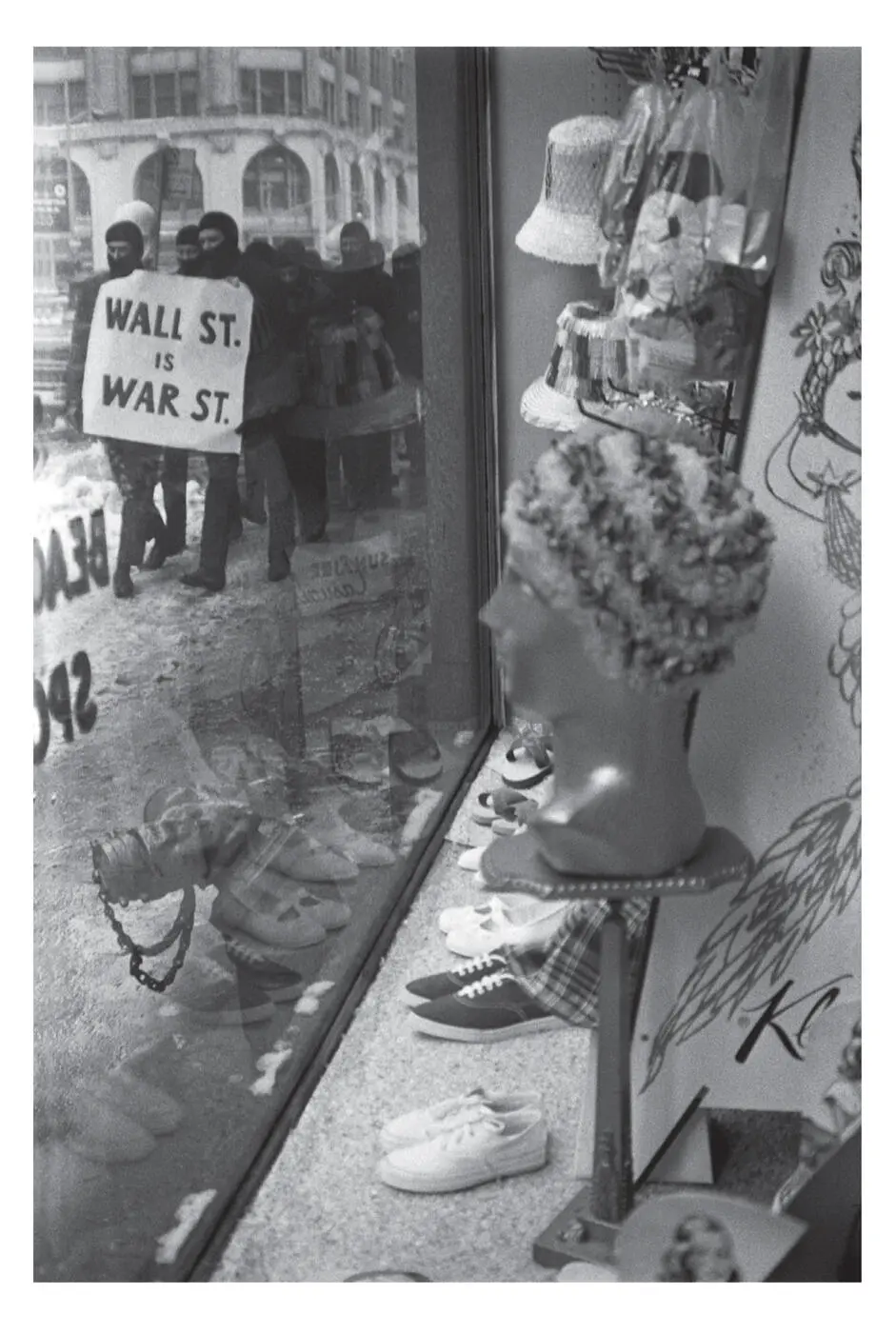

By late 1966, the year the movement formed, the way they were was armed. Armed and ready to battle the Man and his Pigs. They were a Lower East Side street gang with a theory, a call, to liberate people and zones of strategic importance, to colonize an entire quarter of New York City as a network of crash pads, soup kitchens, and arsenals.

They were prepared to requisition all goods that met their needs. The way they were was ready to advance the struggle by any means necessary. The way they were was dangerous. Ecstatic. Angry. Occasionally stoned, but ready to put down the joint and take up the gun at any moment. Taking the City, from Riot to Revolution Bubalev’s treatise was called. From riot to revolution was the point of their arrow. They were looking for people who liked to draw. Who were ready to draw. Pull back the hammer and fire. If you didn’t believe in lead you were already dead. The way they were was unafraid to shoot a Pig in the face. The police were structurally bad, in Bubalev’s formulation. They ratcheted that analysis: the Pigs are assholes, they are the enemy of us and our brother.

The way they were was done with a shitty police state where action was no sister to dreams. The way they were was unafraid. Ready to defend a new and total freedom from Amerikan capitalism and its wars, its deadening effects, its slaveries.

What happens between bodies during an insurrection, Bubalev said, is more interesting than the insurrection itself.

In the rain. In a squat. In an orgy. We meet again.

Fah-Q Motherfucker declared in a 1967 flyer printed in their squat on Tenth Street that in Amerika life is the one demand that cannot be fulfilled. We are here to live, said Fah-Q. To demand our life. Not to request that the needs of life be met. We are here to meet them ourselves, to meet the demand for life .

* * *

Among the Motherfuckers’ many actions in that potent five-year run, 1966 to ’71, some storied, others unknown except to their participants, the following represent a few choice cuts:

* * *

Requisitioned uniforms from an army surplus place on Canal Street, to meet their needs for revolutionary dress: black Levi’s, black T-shirts. Took an entire pallet of each as they were delivered by a wholesale supplier.

* * *

Occupied the squat on Tenth Street, what would become their famed headquarters, in the last days of 1966 and then held a New Year’s feast for their neighbors, burying an entire pig, which they stole from the Meatpacking District, in the sand of the children’s playground in Tompkins Square Park, an effigy of the most hated neighborhood denizen, the uniformed Pig. “Pig roast! Pig roast!” neighborhood children yelled, running up and down Avenue B, bordering the park. The Motherfuckers core group took a lesson from that day, their first big community gathering: the children of the Lower East Side, underfed, runny-nosed, of black and brown complexions, robbed of a lice-free, misery-free existence, robbed of most aspects of childhood, were already soldiers partaking in the struggle. Fah-Q understood, as a survivor himself of the ghettos of Miami, Florida, who and what they were. But he did not recruit them. They joined on their own, a breeze of play, of life, who defended the perimeter of the Motherfuckers’ compound. The Pigs were afraid of those children, who had nothing to lose. In May of ’68 they were breaking up pieces of sidewalk (just as Fah-Q, who gave them pickaxes, had seen it done in the newsreel footage from Paris). That summer the kids heaved concrete and cobblestones at Pigs on their big Harley-Davidson Pigcycles as they rode up Avenue A, one of whom crashed, a big, beefy fellow in short sleeves and knee-high, shiny jackboots. Later that year the children stole an idling ambulance as two paramedics were picking up Chinese food on Houston Street. The kids brought the stolen ambulance straight to the Motherfuckers, who converted it with matte black spray paint and new plates and a removal of most identifying marks. It became their official van, useful for requisitioning goods from appliance stores along the Bowery, items stocked right there on the sidewalk, which they claimed for their own store on Tenth Street, called Free, where they gave everything away.

Читать дальше