Twinbrook, is this a collection or something? What do you want with these names? I’m not going to read the typed stuff. I don’t like reading.

By the time he’d separated the blanker, less intimidating handwritten sheets from those crowded with small print, the sun had passed by the window, and now he realized he’d have a harder time reading unless he turned on the overhead fluorescent.

In fact, most of the typed sheets weren’t typed but photocopied articles from newspapers and magazines. Some of them described freeway accidents or the weather. Others showed beaming brides and grooms, looking, thanks to the copying process, like black-faced riverboat minstrels.

None of these reports seemed connected with any other. But the corporations turned up again. He found two lists of boards of directors, apparently copied from a magazine article. Twinbrook, Twinbrook, Twinbrook. Are you nuts?

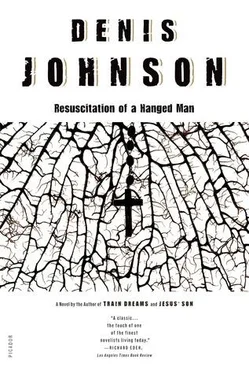

English was out of cigarettes, his eyes felt dry and sleepy, and he’d decided, at what point he wasn’t aware, not to turn on the overhead light for fear of attracting attention. He wasn’t used to this kind of labor, this rowing through a sea of letters and words, and he’d satisfied himself already that he’d made a fair try at getting it done. But he stayed a little longer because, to tell the truth, he wanted to satisfy Ray Sands. Sands was dead, but English still felt his power to approve or disapprove. He was still working for Sands. He was carrying out Sands’s instructions. After all, people didn’t die instantly. Their images lingered, and they had to fade away before you could ignore them.

He carried a folder to the window for a little more light. Across the face of it Twinbrook had scrawled the name SKAGGS. English opened it and was shocked and irritated to read, in Twinbrook’s handwriting:

Brain Death II Veith, FJ

Brain Death I

JAMA 238 (15): 1651—5

10 OCT 77

238 (16): 1744–8

17 OCT 77

life after death:

J Nerv Ment Dis SEP 77

(Stevensn) 165 (3) 152—70

What he could read of these notes seemed to consist mainly of names and numbers and dates; but the dates were old, the names weren’t full names, the numbers weren’t phone numbers.

— 1975 attitudes

British physician

— dead body

— saving life

death — heart lung death

but DRS say should be brain

Twinbrook, you sick bastard, what are you thinking? Are you aware you don’t make any sense?

NYTimes

call wwwwww what is guy’s name?

call people on panel

— get address of wwwwww; where can I get

copies?

later, interview people by phone

The folder held a thick photocopied article: “BRAIN DEATH: I. A Status Report of Medical and Ethical Considerations.” English was terribly thirsty and wanted a smoke. There was a page evidently typed by Twinbrook:

what you are holding in your hands is a book about … etc. And I think it is always a book about the verge in conscoiiouslness, the splitting apart of the world, and the end of time.  I’m not a writer of essays. I

I’m not a writer of essays. I  write first of all because

write first of all because  ETC. talk about the headless man or bodiless head in Brazil what a visitor to this country might think of as a pre-funeral ceremony: strangers who won’t be invited to the funeral driving slowly in single file alongside an accident

ETC. talk about the headless man or bodiless head in Brazil what a visitor to this country might think of as a pre-funeral ceremony: strangers who won’t be invited to the funeral driving slowly in single file alongside an accident

Yeah, I get it. People driving past an accident. I get that. Right, brain death, I get that.

I know more about you than your own mother.

How did panel operate?

Was agreement the general rule?

Did opposing views find compromise

in final report? Or did

some views go down to defeat

while others formed basis for report

findings?

Who does all the work?

Me. I do all the work. You go crazy, and I do all the work.

He must have been missing for years before anybody missed him. English was frightened for this man.

Among the pages, most of them flecked with words in Twinbrook’s tiny, nearly illegible hand, English found the photocopied columns of an old newspaper— The New York Times, a heading revealed, of September 1, 1870; and others from September 4 of the same year. They explained the name SKAGGS on the folder’s cover: in Bloomfield, Missouri, sometime in August of 1870, according to these articles, a man called John H. Skaggs had been hanged for murder. His executioners had marched him up to the front of the scaffold so that he wouldn’t have to look at the noose just at that moment, and asked him if he wanted to talk to the crowd of people who’d come to watch him die. The killer had obliged everyone with a long speech. “I would like for you all to have some sympathy for me,” he told them; and, talking specifically to the young boys: “In the first place avoid drinking of whiskey; and in the next place avoid the love of money better than you do your God; and in the next place whatever you do avoid lewd women. I want every little boy that hears me to remember that until he lies on his death-bed; then when he is on his death-bed he cannot foller after these things, and never forget it whatever you do.” His sentimental sermon rushed down the column and the printed words seemed to shrink on the paper. “I don’t know but what there is some here on this ground that looks upon me probably as a tyrant, as an outrageous — a tremendous man, but then that is not for you to judge, for you know not. I hope, therefore, that no lady nor no gentleman will look upon me with any contempt as disgraced in my name. I would be glad how well you may all do; I hope to meet you in the better world than this troublesome world is. This world is nothing but sinfui — nothing else; one sin will lead to another. I hope this may be a warning to every one of you, that when you go home, and after you eat your supper and lie down in your bed I hope this may run through your hearts, not only one time, but as long as you live. I think that I know that it is a mighty horrible thing to be brought up right at death’s door and stared in the face. There is none of you like me; you have no idea …” Maybe this incident was long past and everybody involved in it was dead, but English was filled with embarrassment. The guy should have spat on the onlookers.

English wondered how the townsfolk must have felt watching the finish of a person’s life. Death wasn’t such a stranger to them, probably. The people of Bloomfield in 1870 had probably, every one of them, strangled chickens with their bare hands and shortly afterward eaten them, and seen close relatives languish in their final illnesses at home, and one or two might even have had a loved one dying in an upstairs bedroom while they attended John Skaggs’s execution. To watch a public hanging might have been a fascinating and exciting, probably a troubling, possibly even a terrifying and humbling experience. But it wouldn’t have altered the shape of the soul of a Bloomfield resident.

English thought of those days, the mornings, afternoons, and evenings before the First World War, as a time when everything made sense. Everybody shared a philosophy of life as basic as the soil and as obvious as the sky. You couldn’t go sixty or sixty-five down a turnpike and end your journey in a city of thunder and smoke. He envied the people of Bloomfield their assumptions, even though he couldn’t have said, exactly, what their assumptions had been. He just knew that in those days the world had been founded on things everybody understood.

Читать дальше

I’m not a writer of essays. I

I’m not a writer of essays. I  write first of all because

write first of all because  ETC. talk about the headless man or bodiless head in Brazil what a visitor to this country might think of as a pre-funeral ceremony: strangers who won’t be invited to the funeral driving slowly in single file alongside an accident

ETC. talk about the headless man or bodiless head in Brazil what a visitor to this country might think of as a pre-funeral ceremony: strangers who won’t be invited to the funeral driving slowly in single file alongside an accident