A bruised left eye was a good clue. But she didn’t find Dara. Instead, she saw several women with bruised eyes or cheeks from the beatings of their husbands’ fists.

She had completely given up hope when one day, near her house, she suddenly felt her heart explode and her knees weaken. It was walking toward her. A left eye with a conspicuous black bruise under it. Excited and embarrassed, Sara looked the other way. She even considered turning around and changing course. However, when she managed to regain her composure, she turned and looked at the young man’s face again. She recognized him. He was one of the pestering admirers who used to stand in front of her house. He would hold his thumb and pinky up against his ear mimicking a telephone and then he would point to the wall behind him where in red paint he had written his cell phone number and drawn a broken heart next to it. Sara was shocked and disappointed. She worried that this ugly, vulgar, and undignified man was the Dara of her dreams. The pestering admirer saw Sara, too. But he quickly turned around and with long and rapid strides walked in the opposite direction. In effect, he ran away. Sara breathed a sigh of relief. She was now certain that the man was not Dara. In that last moment before he turned around, Sara noticed the young man’s right eye. It too had a bruise under it.

“Hello Sara,

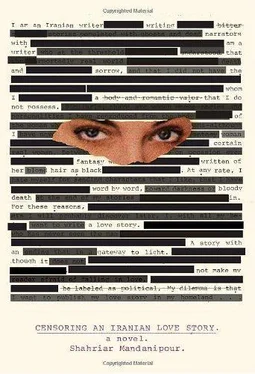

“Thank you for writing that two-sentence letter. I am truly honored. But it really did me in. By the time I searched every single page of War and Peace to find the fifty-nine letters you marked, my eyes were all swollen. Even Natasha wasn’t as mischievous as you. To make sure no one discovers your letter, even though it is very unlikely, I erased the dots and returned the book to the library; just the way all the dots from the letters I have sent to you have been erased. Life isn’t so pleasant these days. I may not be able to write to you or to even see you anymore. I used to be in prison. I was released on the condition that I would not leave the city. Once a week I have to go show myself and sign. These days, the more I swear that I am no longer involved in political activities, the more they suspect me. I have even confessed that I have fallen in love and now detest any and all ideologies, but … As always, I wish you happiness …”

This was the last letter Sara decoded from the pages of Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People. This book too had been carefully hidden for her behind a stack of dusty books. Sara no longer saw a sign or a dot from Dara …

Dara disappeared.

Something was lost in Sara’s life. She felt lonelier than ever before. She read more novels and stories than ever before. She told herself that Dara had read them, too, or was reading them now. Unlike in the past, she looked at the faces of the people on the street; she felt she liked them because one of them may have spoken to Dara or perhaps knew him. She especially looked at the faces of the street peddlers, but she saw no sign of familiarity in their eyes. Sometimes she thought Dara may have had some sort of a physical handicap. Sometimes she thought Dara had tricked her, anyone else would have shown himself to her at least once … Until at last, on that spring day, in front of the main entrance of Tehran University, on the fringes of the impassioned student demonstrations, Dara introduced himself to her and their adventure began …

Years before Sara and Dara’s first meeting, I had the honor of meeting Mr. Petrovich. In those days I was a young writer who in his solitude had spent years carefully reading novels and stories. I had even extracted the styles and techniques of all sorts of classical and modern writers from their books and had noted them on index cards. I had then concluded that every writer must have his own particular worldview and philosophy. I therefore read as many books on philosophy as I could. To successfully analyze my characters, I read the equivalent of a university degree in psychology. I had Freud and Jung and their followers in one hand, and Pavlov and his followers in the other, until I arrived at American psychology. Next, I told myself that a great writer will never become a great writer if he is not well versed in world history and politics. Therefore, as a social and literary responsibility, and despite my family’s trepidations, I chose political science as my field of study at the university. Before I left Shiraz for Tehran and Tehran University, my father, who was a wealthy self-made man, pulled me aside and said:

“Look here, son, there’s no future for you in political science. The best jobs for political science graduates are at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. But positions like ambassadorships and director generals and whatever else belong to the relatives of the Shah and his royal court. They won’t even make you a mere clerk.”

My father was absolutely right, and that is why I disagreed with him. He went on to say:

“What’s more, if you study political science, because you are a very emotional person, there is a good chance you will end up joining some antigovernment political group, you’ll become a Communist, an urban guerrilla, and you’ll end up having to deal with the secret police. By the time they’re done with you, if you are not executed or sentenced to life in prison, because of the hot baked potatoes and the Coca-Cola bottles they have shoved up your ass, you’ll be walking funny for the rest of your life … Go to America, study engineering or medicine, and become the pride of your family and your country.”

At the time, I could not tell my father that I did not want to become a Communist, nor did I want to be an ambassador … Therefore, against his advice, I went and studied political science. I wanted to go as far as a doctorate degree, but first came the revolution, then the war, and I who wanted to become a great writer told myself that many of the world’s great writers have experienced war, and so I signed up for military service and volunteered to go to the front. The first outcome of the Iran-Iraq War was millions of dead and disabled; the second outcome was that right after peace was established we realized that we were two Muslim countries and therefore brothers. It seems the war also wanted to offer the world another great writer, and for this reason, after eighteen months, it sent me back to my hometown, Shiraz, alive and well. And I, who even in the trenches had spent my time reading novels from the farthest reaches of the world —The Soul Enchanted, David Copperfield, Moulin Rouge, Resurrection, and … and … and had not stopped the exercise of writing, was fully armed and ready to write my first masterpieces and to present them to the world.

Ask me:

Was all this self-praise, as with other bigheaded writers, just to claim you are a great writer?

And I will answer:

You are wrong again. No, I didn’t say all this to suggest that I am a great writer. I said it all to explain why I have not become a great writer. In other words, I want to say that I was just another young man with Great Expectations of my future as a writer. In 1990, I was thrilled to learn that on the advice of Hooshang Golshiri, one of Iran’s great writers, a reputable private publisher had agreed to publish the second collection of my short stories, titled The Eighth Day of the Earth. Every day I sat waiting for the telephone to ring so that I could hear my publisher’s voice telling me that my book had been printed. I waited for almost a year, until one day I finally heard his voice on the telephone.

“Shahriar! We’re screwed! I’m ruined … The Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance has complained of thirteen separate points in your book — all sexy words and phrases … You have to come to Tehran. What a mistake I made investing in a young writer. My capital … I’m ruined!”

Читать дальше