“Shut the hell up!”

He puts pen to paper to underline the word “dance,” but realizes that the writer himself has instead used the expression “rhythmic movement.” He pounds his fist on the page. A few of the more cowardly and conservative words quiet down, but amid the racket of the others there is sarcastic laughter. Overwhelmed, Mr. Petrovich gets up from behind his desk.

It is because of these emotional tortures that at times examining one book can take as long as a year, or five years, or even twenty-five years.

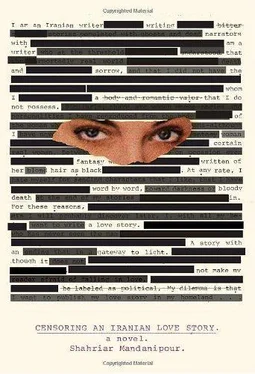

So it is that many stories, especially love stories, in maneuvering their way through the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance either are wounded, lose certain limbs, or are with finality put to death.

In the love story I want to write, I will not run into any difficulties as long as in the opening sentences I depict the beauty of spring flowers, the fragrant breeze, and the brilliant sun in the blue sky. However, the minute I start to write about the story’s man and woman and their actions and conversations, Mr. Petrovich’s perspiring, irate, and reprimanding face will appear before my eyes.

Ask:

What do you mean?

So that I reply:

In this love story, I must have a feminine protagonist and a masculine antagonist, or vice versa. Now surely, with an Unbearable Lightness of curiosity you want to ask: Shouldn’t there be a man and a woman in an Iranian love story?

Ask, and I shall answer:

Well, in Iran there is a politico-religious presumption that any proximity and discourse between a man and a woman who are neither married nor related is a prologue to deadly sin. Those who commit such prologues to text, and such texts to sin, in addition to retributions that await them in the afterworld, will in this world too be sentenced by Islamic courts to such punishments as imprisonment, whiplashing, and even death. It is to prevent such prologues and deadly sins that in Iran, females and males in schools, factories, offices, buses, and wedding parties are kept apart. In other words, they are protected from each other. Of course, several revered clergymen have opined that pedestrian traffic on sidewalks too should be segregated. They know that in the modern world they must present plans founded on scientific research, therefore, based on the findings of their experts, they have presented their plan as such: In the morning, for example, men will be permitted to walk along the sidewalks on the right side of the streets, and in the afternoon, the women. Conversely, on the sidewalks flanking the left side of the streets, in the morning women, and in the afternoon men, will be allowed to come and go. As a result, both sexes will have access to shops on both sides. A few of these clergymen even object to and criticize movies that have received a screening permit from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, because in rare scenes the actor and actress playing husband and wife, or brother and sister, are shown alone together in the kitchen or the living room. These gentlemen reason that a man and a woman who are not mahram— meaning neither married nor immediate kin — should never be alone together in a room or any enclosed space.

In response to such criticisms, numerous experts and ministers from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, as well as film directors, cinematographers, and other crew members involved in movie production, have in lengthy and frequent articles and interviews explained: “Gentlemen! Don’t worry. In scenes where it appears that an actor and an actress are alone, there are, in fact, behind the scenes, meaning a little farther away from the camera, tens of crew members present — including the director, the assistant director, the stage assistant, the cameraman and his assistants, lighting crew, and …” Despite these explanations, several of the complaining gentlemen have suggested:

“Let us assume it is so. But the audience only sees a man and a woman alone in a room. And the fact that a man and a woman are alone in a room will lead the audience’s imagination to a thousand sins.”

I hope this introduction has helped you understand why publishing a love story in Iran is not a simple undertaking …

Now ask me how I hope to write and publish a love story, so that I can explain:

I think because I am an experienced writer, I may be able to write my story in such a way that it survives the blade of censorship. In my life as a writer, I have come to learn Iranian and Islamic symbols and metaphors very well. I also have plenty of other tricks up my sleeve that I will not divulge. The truth is that a long time ago, I never really intended to write a love story. But that boy and girl who meet each other near the main entrance of Tehran University and in the chaos of political demonstrations stare lovingly into each other’s eyes have convinced me to write their story.

They have known each other for about a year and have shared many words and sentences. But it is on this spring day that the girl for the very first time casts her eyes on that boy’s face … Don’t be surprised by the paradox in my last two sentences. Iran is a land of paradoxes … If you ask:

Did they meet on a matchmaking Web site?

I will emphatically say:

No…

And even more emphatically I will suggest that these two characters are far too innocent and fictional to meet on a matchmaking Web site or on Web sites where one seeks a sex partner … In fact, such Web sites are banned in Iran. But allow me to tell my story.

As you have realized, the girl’s name is Sara. And the boy’s name is Dara. Don’t ask, I confess, the names are pseudonyms. I don’t want the real characters to face any problems for sins or illegal acts that they may commit in the course of my story … Of course, selecting Sara and Dara as pseudonyms from among thousands of Iranian names has its own story, which I must tell:

Once upon a time, long ago when I was in school, Sara and Dara were two characters in our first-grade textbooks. Sara was there to introduce the letter S and Dara to introduce the letter D … Long ago in Iran, not an Islamic regime but a monarchist regime ruled. From that regime’s perspective, there was no problem for Sara and Dara, after having been introduced to schoolchildren, to appear alone in a room in other lessons to talk, for example, about a parrot so that the letter P could be taught. In those bygone days, Sara was illustrated with long black hair and wearing a colorful shirt, skirt, and socks, and Dara was drawn wearing a shirt and pants. They were beautiful, but we schoolchildren used to draw a mustache for Sara and a beard for Dara … Years later, I mean when I was a student at Tehran University, we Iranians grew tired of the monarchist regime and started a revolution. Our reawakening began when the Shah, following the advice of U.S. president Jimmy Carter, claimed that he wanted to give the people of Iran political freedom and the freedom of speech and thought, and to demonstrate his goodwill he dismantled the Rastakhiz Party — the only political party in the country which he himself had created. We shouted “Freedom!” … We shouted “Independence!” … And a few months after the start of our revolution, to our shouts we added “Islamic Republic!” … Across the country we set fire to banks because, according to the covert and overt propaganda of the Communists, banks were symbols of the bloodthirsty regime of bourgeois collaborators. We set fire to cinemas because, according to the covert and overt propaganda of the intellectuals, cinemas were the cause of cultural decay, the spread of Westernization, and the increasing influence of American Hollywood culture. We burned down cabarets, bars, and brothels because, according to the covert and overt propaganda of the devout, they were centers of corruption and propagated deadly sins … Well, a few years after the revolution’s victory, in first-grade textbooks, there was a headscarf covering Sara’s black hair and a long black coverall hiding her colorful clothes. Dara was not old enough to grow a beard, therefore only his father grew one. According to our religious teachings, a Muslim man must have a beard and must not groom his face with a razor lest he look like a woman.

Читать дальше