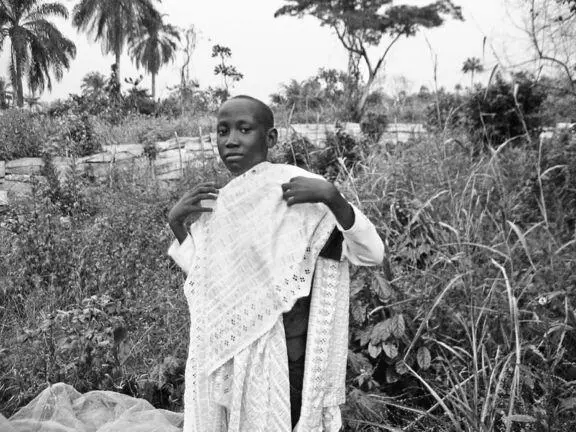

Muyiwa shakes his head. I look at Mrs. Adelaja again, this woman in whose radiance I can see nothing that looks like grief and nothing that looks like the terrible humiliation in the story. But this is what those bastards have saddled her with for the rest of her life: the memory of the man she loves forever tied to the degradation of that one night. I muse on how they would have gone to bed that evening like any other aging married couple, perhaps with tender words, or perhaps in the midst of some minor tiff, with no thought of the violence that would soon tear them from each other. I imagine her in the weeks and months afterward, her beautiful face disfigured by sorrow. And then the gradual courage to continue, the strength she had to find for herself and for her children. Fortitude beyond imagining. It is a great and painful wonder to me, just at that moment, that there is no trace of it on her face, no visible mark, seven years on.

Under the white canopy, the bride’s family has begun to serve soft drinks and jollof rice and moin-moin . I look around at the groom’s family, my family. The men wear purple aso oke caps, the women shiny purple geles . My family, all of whose lives time has altered inexorably. Each face on which my eye rests brings me up short. I see Aunty Arinola, Uncle Tunde’s older sister, whose husband collapsed at a market in Benin City, his corpse ignored by the public for hours. Two seats from her is the jovial friend of the family, Mr. Hassan. He is my cousin Adebola’s godfather; his wife of twenty-seven years was killed in a car crash last year. And I consider myself, consider my own loss, too. Father’s memory has already become so insubstantial, fixed to a few events only: a birthday party, a day at the beach, a discussion one evening in the kitchen while I cleaned a fish and he sat at the dining table looking over some notes from work. I cannot even remember what we talked about that night. All I have is the memory of sawing away at the gills while he looked up intermittently from the stack of reports in front of him and talked to me. Sometimes I try to make a mental image of his face at that table on that night, and I fail. I still have photographs, but I no longer know what my father looked like.

The air under the canopy is full of the aroma of food. We pass plates of rice and chicken down until everybody has one. The invisible past, on this day of celebration, as on every day:

And there, behind it, marched so long a file

Of people, I would never have believed

That death could have undone so many souls .

Pastor Olakunle strides up and down the stage. He is all energy. He stops, peers into the camera, holds up his Bible, and breaks into a wide white grin. He breathes heavily into the microphone: God is good. God is gooood . Pastor Olakunle is delivering a teaching to the faithful. This is a mighty word that the Lord has laid on his heart, praise the Lord. God doesn’t want you to be sick, God doesn’t want you to die. If only you would believe. You. Shall. Be. Healed, praise the Lord. Our God is not a poor God, nor is he wretched. His true followers can be neither poor nor wretched.

Pastor Olakunle is attired in a silk suit. His shoes are of fine Italian leather, his accent is American, as befits a prosperous man, praise the Lord. Pastor Olakunle is intoxicated with the joy of the Lord. He jumps up and down. One more thing, he says, and this is wonderful: once you are walking in faith, you shall never be sick again. Yes, you heard it right. The Lord will banish all sickness from your life. Healing is yours, in the mighty name of Jesus.

Pastor Olakunle owns several Mercedes-Benz cars. It is not clear if he is living as victoriously as Pastor Michael, who, as is well known, owns both a Rolls-Royce and a Lear-jet, praise the Lord. But who also, inexplicably, has just died. The Lord moves in mysterious ways. Nevertheless, our God is not a poor God, and Pastor Olakunle does very well. The Church of the New Generation is filled to the rafters, praise the Lord, and when he gives the word about permanent healing, a woman in the audience raises her hand in awe and adoration of the mighty name, rises to her feet, swoons.

Adebola, Muyiwa’s brother, had just been born when I left home. Now he is in Class Two of the senior secondary school, thinking about going to university in a year or two. He is a bright boy, ranked in the top twenty in a class of over 250. He is thoughtful and good-natured, and attends Mayflower School in Ikenne, Ogun State. Mayflower, one of Nigeria’s most reputable boarding schools, was founded by Tai Solarin in 1956. Solarin was a maverick, much persecuted by the successive military juntas that misruled the country. He died in 1994, and many Nigerians continue to hold him in highest esteem. One reason for this is that, for most of his life, he led the campaign to make elementary education free and compulsory in Nigeria.

— Tai Solarin was a humanist, Adebola says.

— That’s right, I reply. And do you know what a humanist is?

— Yes, of course. A humanist is someone who doesn’t believe in God.

— Oh no, Adebola. That’s not the definition of a humanist.

— Tai Solarin is a humanist. And Tai Solarin doesn’t believe in God.

— Both of those things are true. But neither follows from the other. A humanist is someone who believes in humanity, someone who celebrates human ability and potential. That’s where we get the word “humanities” from. A person who doesn’t believe in God is an atheist.

— A humanist is someone who doesn’t believe in God. That’s what we were told at school.

One goes to the market to participate in the world. As with all things that concern the world, being in the market requires caution. The market — as the essence of the city — is always alive with possibility and danger. Strangers encounter each other in the world’s infinite variety; vigilance is needed. Everyone is there not merely to buy or sell, but because it is a duty. If you sit in your house, if you refuse to go to market, how would you know of the existence of others? How would you know of your own existence?

When I start speaking Yoruba, the man I’ve been haggling with over some carved masks laughs nervously. “Ah oga ,” he says, “I didn’t know you knew the language, I took you for an oyinbo , or an Ibo man!” I’m irritated. What subtle tells of dress or body language have, again, given me away? This kind of thing didn’t happen when I lived here, when I used to pass through this very market on my way to my exam preparation lessons.

The Tejuosho bus stop, a stone’s throw from where I stand, is a tangle of traffic, mostly danfos and molues, that one might be tempted to describe as one of the densest spots of human activity in the city, were the description not also true of many other neighborhoods: Ojuelegba, Ikeja, Oshodi, Isolo, Ketu, Ojota.

“Well now that you know I’m not a visitor, you will agree to give me a good price, abi ?” He shakes his head, searches for excuses. “ Oga , times are hard, I am not charging you high.” He still suspects me of carrying more money than I know what to do with. The masks are beautiful, but the price he is asking is exorbitant. I leave his shop and move on. Other vendors call me. “ Oga , boss, look my side now, I go give una good price.” Others simply call out: “Oyinbo.” “White man.” Young men sit in the interiors of the small stalls on raffia mats or on low stools, their limbs unfurled. They are passing time, waiting for the next thing, in bodies designed for activity far more vigorous than this. I move through the warren of shops, which, like a souk, is cool and overstuffed, delighting in its own tacky variety, spilling seamlessly into the cavernous indoor shop. Piles of bright plastic buckets line the entrance, and beyond them, the cloth merchants — these ones are women, alhajas —swaddled in laces and looking out with listless gazes. The hall is not well lit. It is as if the outdoor market is reclaiming for itself what had been designed to be a mall. It was my favorite of all the markets, because of this interior coolness. The only movement here is from the stream of customers, and the slow surveillance of the standing fans. The concrete underfoot is curiously soft, tempered with use. Then I emerge to sunlight and the sudden hysteria of car horns and engines. Six roads meet here and there are no traffic lights. Congestion is the rule, to which there is rarely exception. Here, I’m told, is where the boy was killed.

Читать дальше