Snow is total. It robs the street of details and muffles the goings-on outside the window. In the warm interior of the apartment, my body is still responding to the difference in time zone. It is five in the morning. I have insomnia. I hold a cup of tea in my hands. And, as I sit there, a memory of Lagos returns to me, a moment in my brief journey that stands out of time.

I am there again, in the area around St. Paul’s Anglican Church, Iganmu, where colonial-style buildings crumble next to makeshift roadside shacks, and the unkempt façade of the Government Press building faces the shiny glass doors of a Mr. Bigg’s. Here, the city becomes as trackless as a desert. It is a hot Thursday afternoon. People are hard at their work, and I alone wander with no particular aim. On house after house is painted the straightforward but nonetheless intriguing directive: “This house is not for sale.” Little streets wind in upon each other like a basketful of eels; no two run parallel. Losing my geographical bearings in this way always brings ambiguous emotions. Not knowing where I am exposes me to various dangers, and there is always a possibility that I will be accosted by a hostile party. On the other hand, letting go of my moorings makes me connect to the city as pure place, through which I move without prejudging what I will see when I come around a corner.

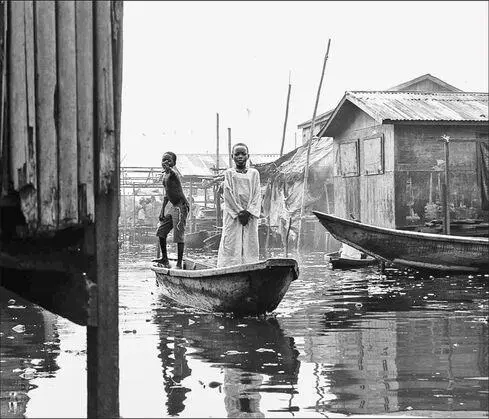

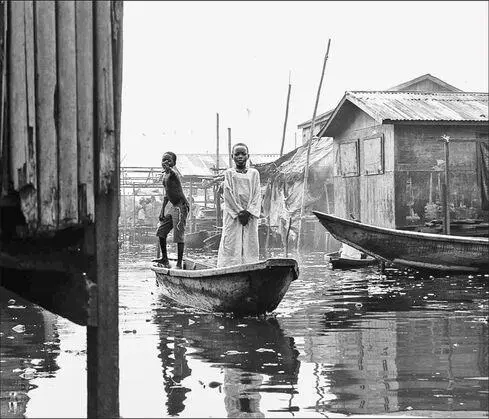

I am in a labyrinth. A labyrinth, not a maze: I hadn’t really thought about the difference before, but it has become clear. A labyrinth’s winding paths lead, finally, to the meaningful center. A maze, in contrast, is full of cul-de-sacs, dead ends, false signals; a maze is the trickster god’s domain. When I enter a little sun-suffused street in the heart of the district, I sense an intentionality to my being there. It feels like a return, like a center, though it is not a place I have ever been before. It is an alley, and it is full of boats. The boats are in storage. Their prows jut out from the bottom floor of each of the buildings on one side of the street. The buildings are mostly two or three stories high, and the alley itself is no longer than 150 yards. Because the sun is high and I am disoriented, I cannot really tell if this is the street’s south side or its north. Across from the buildings, there is a concrete wall behind a stand of three large trees. The wall runs the length of the alley and, underneath the trees, there are young children playing. A woman cooks beans in a large basin. This side of the street is dappled. As I move, or rather as I am pulled, into the little street, as one might be pulled by the broad strength of a receding tide, I see that the jutting shapes are not boats at all. They are coffins, dozens of them, in different sizes and various states of completion, presented in sober and matter-of-fact array.

There are no cars parked on the narrow street, just one or two motorbikes. But there is a lot of activity. Men, bare-chested or in white singlets, work wood with saws, planes, and other carpentry tools. Their bodies glisten in the half shadows of the shops. There are so many of them, it must be a kind of carpentry consortium: this is evidently where they do all their work and live with their families. But their only product, as far as I can see, is coffins. No chairs, tables, wardrobes, or anything else. Only coffins, some painted white, some stained to a lustrous finish, many others pale and as yet unstained. A few wide planks rest on the wall across the street. A darkly polished casket lies on a trestle. It is grand, with brass handles, and looks as out-of-place and unsurprising as a Rolls-Royce parked in a ghetto. It is half-open, revealing a tufted interior encased in plush white satin: an invitation to sleep.

I want to take the little camera out of my pocket and capture the scene. But I am afraid. Afraid that the carpenters, rapt in their meditative task, will look up at me; afraid that I will bind to film what is intended only for the memory, what is meant only for a sidelong glance followed by forgetting. A tall man in a sky-blue cap rhythmically moves his arms back and forth over a butter-colored plank. His arms are lean and black, and he has one eye closed as he works. The shavings fall in a nest about his feet. He is ankle-deep in that soft wood-stuff which, I suddenly remember, was so fascinating to me when I was a child of seven or eight. I remember the carpenter who made our furniture, the pile of shavings in his shop, and the sweet, oily fragrance they emanated, an aroma that fit the playful nature of the material, those buoyant curls of gold that seemed to transcend the timber that originated them.

There is a dignity about this little street, with its open sewers and rusted roofs. Nothing is preached here. Its inhabitants simply serve life by securing good passage for the dead, their intricate work seen for a moment and then hidden for all time. It is an uncanny place, this dockyard of Charon’s, but it also has an enlivening purity. Enlivening, but not joyful exactly. A wholeness, rather, a comforting sense that there is an order to things, a solid assurance of deep-structured order, so strongly felt that when I come to the end of the street and see, off to my right, the path out of the labyrinth and into the city’s normal bustle, I do not really want to move on. But I know, at the same time, that it is not possible for me to stay.

The children cry out from the shadowed side of the street as they play with an old bicycle wheel. One toddler, left out of the fun, begins weeping, until a sibling sweeps him up and tickles him and he gurgles with delight. The woman keeps stirring her beans, putting a finger in to taste them. This is the street to which the people of old Lagos, right across the social classes, come when someone dies. They come with great fanfare if it is an old person, order the most expensive casket in celebration of a life, hire out the football field of a secondary school, throw a large party with canopies and live music and colorful outfits. But if the deceased is a youth, fallen before the full fruition of life, the rites are performed under grief’s discreet shadow, a simple box, no frills, a small afternoon burial on a weekday, marked by bitter and unshowy tears, and attended by neither the parents nor by the parents’ friends, for the old should not see the young buried. The carpenters, I am sure, have borne witness to all this. And there are, perhaps, women in the back rooms of their humble houses who help prepare the bodies for their last journey, washing down what remains of a father or mother or child, fitting the heavy limbs into new clothes, putting talcum powder on the face, working coconut oil into the hair and scalp.

TEJU COLE was born in the United States in 1975 and raised in Nigeria. He is the author of Every Day Is for the Thief and Open City , which won the PEN/Hemingway Award, the Internationaler Literaturpreis, the Rosenthal Family Foundation Award for Fiction from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the New York City Book Award, and was nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His photography has been exhibited in India and the United States. He is Distinguished Writer in Residence at Bard College.

www.tejucole.com

@tejucole

Find Teju Cole on Facebook