I raise an eyebrow.

— What’s the difference?

— Cost. The expatriate teachers cost much more.

I check the fee schedule in the brochure he gave me. What he says is true. It is a sour note. What they are saying is that even a Nigerian teacher who studied at, say, the Peabody Institute or the Royal Academy would be paid at a much lower rate than any white piano teacher.

— But the most important thing, which we emphasize to all incoming students, is that you must own the instrument you wish to learn. We try to be clear about this, but people still act confused. If you want to learn piano, you must have a piano at home. If you want to learn cello, you must own a cello. Flute, trumpet, whatever your instrument is, you must own it.

— Voice?

He chuckles. They have set the bar quite high. Owning a piano, even in the West, is no easy thing. In Nigeria, it is prohibitively expensive for all but the most moneyed. Yet, I can see immediately how complicated it would be to have a rental system in Nigeria, a country in which credit facilities are not well established, and most things, including cars and houses, are still paid for in cash. On the other hand, students could not be compelled to come to the school to practice four or five days a week, the minimum that would be needed to gain proficiency on an instrument. The transportation situation would make that too burdensome. What this means is that, for now, serious musical instruction in Lagos is available only to the wealthiest and most dedicated Nigerians.

Yet, it is better than nothing. As demand and supply both increase, prices will be adjusted. Things will become more egalitarian, the way they already are with private secondary schools. The MUSON School already represents a great leap forward: nothing of this kind was available when I was a high school student. I did not discover my passion for music until I went to America. A younger set of Nigerians might not have to rely on going overseas to develop this area of interest.

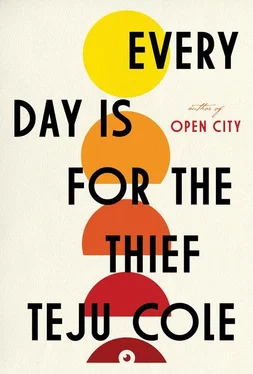

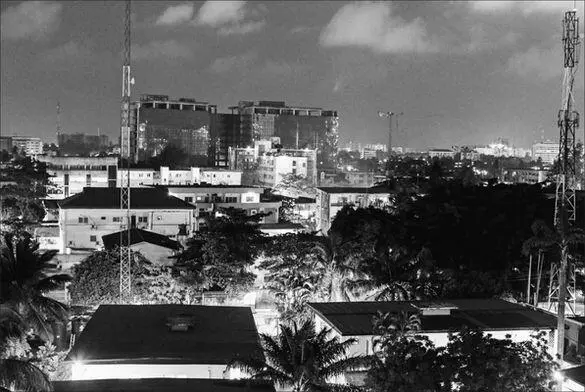

The school, and the bold programming of its concert halls, cheers me greatly. To the extent that places like the National Museum kill my desire to live in the country, institutions like the MUSON Centre revive that will. It is important for a people to have something that is theirs, something to be proud of, and for such institutions to have a host of supporters. And it is vital, at the same time, to have a meaningful forum for interacting with the world. So that Molière’s work can appear onstage in Lagos, as Soyinka’s appears in London. So that what people in one part of the world think of as uniquely theirs takes its rightful place as a part of universal culture.

Art can do that. Literature, music, visual arts, theater, film. The most convincing signs of life I see in Nigeria are connected to the practice of the arts. And it is like this. Each time I am sure that, in returning to Lagos, I have inadvertently wandered into a region of hell, something else emerges to give me hope. A reader, an orchestra, the friendship of some powerful swimmers against the tide.

One evening, a man walks into the living room. He makes straight for me and locks me in a powerful embrace. The features come together very slowly. But when he grins I have it figured out. This stranger is no stranger. It is Rotimi, my childhood friend.

— Look at this guy.

— How the hell are you?

— What have you been doing with yourself?

— Can’t complain. Dealing with this country, and the country’s dealing with me. You know.

— Doesn’t look like it, man. You’re looking good. Come here, fool.

We embrace again. His eyes flash like gemstones in the velvety setting of his face. I can’t believe it is him, after all this time. And yet it is him, it can only be him, that unmistakable grin. Same as it was when he was a shy five-year-old. Rotimi tells me he is now practicing as a physician. He knows I am training in psychiatry. We just sit there and look at each other in amazement for a while, as if trying to reconcile the image of the children we were with the men we now are. He has his life together, he is a made guy. Purple shirt, silver tie. Very smooth. I grab two bottles of beer from the kitchen. And we sit down and talk. Fifteen years of catching up to do.

— I’m so happy to see you, he says.

— I’m happy to see you too. So tell me, man, what’s the scene like here? How’s medicine in Naija?

— Ol’ boy, it’s not easy o. It’s not easy at all.

— Yeah, everyone says that. But doctors do better than others, no be so ?

He loosens his tie and leans back. How quickly time takes hold of us. The diffident kid I knew since I was myself an infant, and here he now is, a man resting after his day’s labor. I look at his hands. In those hands is new knowledge.

— How are the cases?

— The cases are okay, you know. Very wide variety. But it’s a private hospital, and they do a pretty good job of keeping it supplied with drugs, equipment. Well anyway, I’m thinking of going into pediatrics.

— That’s good.

— Should be fine. The kids are okay, actually, it’s the parents that are difficult. They’re the hardest part of pediatrics. Anyway, I’ll do general medicine for a while yet.

— Yeah, I did my last few rotations in internal medicine last year. There’s a part of me that’ll miss that. But the “talking cure” is a much better fit for me.

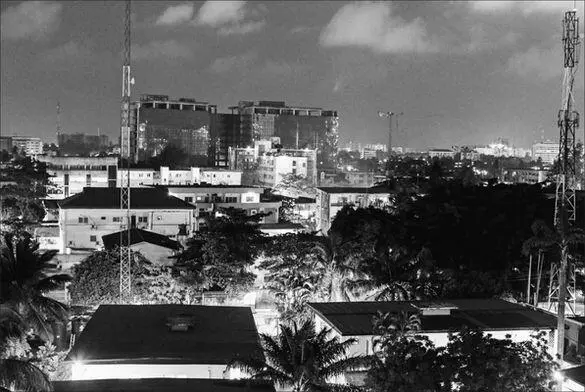

It is starting to get dark inside the living room, though the sky is still the color of burnished copper. I switch on the lights. These Lagos nights that fall without warning: the last glow of day at a quarter to seven, pitch-black fifteen minutes later. The call to prayer floats in from the distance.

— Well paid?

— Not really. I mean, I live with my parents, so I can manage. But it’s not great.

— What are we talking, a hundred?

— More like seventy.

I whistle. Seventy thousand naira a month, for a doctor in a private hospital. I hadn’t expected it to be so little. That comes to five hundred dollars a month, a pittance. And there’s no real adjustment to make for cost of living because, in Lagos, television sets cost just as much as they cost elsewhere. This is the reality in an economy that is almost totally dependent on imports. A used car will set you back ten thousand dollars, same as in the United States, and a new paperback novel costs fourteen dollars. Meanwhile, rent is not cheap, and though salaries have risen, they have not kept up with the rate of inflation at all. It is difficult for the average Nigerian to live a middle-class lifestyle. And even those whose profession or education gives them an income well above the average still struggle. And for those in the fifteen-thousand-, twenty-thousand-naira range, life is simply hell. A hundred and forty dollars a month is poverty, anywhere in the world.

— Seventy? So who is making the money? Used to be that doctors were financially well off. Heck, isn’t that why our families pushed us to study medicine?

— No kidding. Well, it’s not like that anymore. To be a big pawpaw in Nigeria now, you’d better have a job in telecommunications. Or better still, in the oil industry. That’s where the moola is. I have friends I went to school with who graduated and went straight into positions that pay three hundred, four-fifty even. Bankers do okay too, two hundred, you know, and more at the merchant banks. But let me tell you, life is hard in Nigeria, man. Life is very hard for the majority. We’re all looking to get out. America, London, Trinidad. Wherever.

Читать дальше