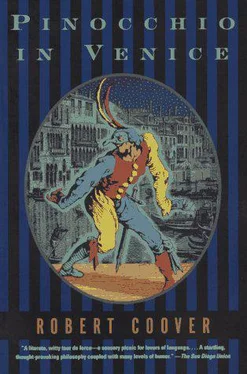

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"No, of course not, but I'm afraid I don't — "

"Have an opus at hand? Do not concern yourself, maestro, for we have traduced a little volume of our own. Psst! The book, you little turk's head!" The nun, he sees now, has a book clamped under one arm, but the arm seems disabled. Reaching for the book with her other arm, she drops the cane. Stooping for the cane, she drops the book. She feels around blindly for the book, but the priest steps crunchingly down upon her black-gloved hand and, sighing deeply, picks up the book himself, hands it to the professor with an uncapped pen.

"Your — your colleague, she's — "

"Yes, blind in all her two eyes, excellency, from too much devotion to the noble battologies of your ambagious texts. Now, if you would be so kind "

Wearily, he opens the book to the flyleaf. He has signed millions of these things in his lifetime. The gesture is automatic. The book, however, is not an edition he recognizes. After signing it, he turns to the title page. For a moment he cannot comprehend what he is seeing. The letters stand there on the page like a row of rigid pine trees or the teeth of a saw. "Where — where did you get this — ?!" he gasps, as the priest takes the book back and loses it in the voluminous folds of his cassock, the nun still whimpering under his planted foot.

"Why, in the little bookstore by the Rialto bridge, dottore. Everyone is reading it. It is a worldwide success!"

"But — but that's impossible — !"

"Ah, you are too modest, signer professore. I insure you it has been festooned by the most fulsome praise and garlanded with the ambrosia of excessive honor!" grimaces the priest, holding back a wheezing cough. The nun, too, on her feet once more, is shaking so hard with inner convulsions, she has to lean against the priest not to fall down again. "Perhaps you would like to peruse some of the recent reviews from La Repubblica or the Corriere della Sera?"

He takes with trembling fingers the clippings the priest hands him. "Mamma, the final opus magnum of the Nobel Prize-winning art critic and historian Dr. Pinenut," he reads through his blurring vision, a shudder shaking him violently from head to foot, "has been universally declared, upon its posthumous publication this week by the Aldine Press, in cooperation with the executors of the author's estate, to be, if not his greatest masterpiece, certainly his most revealing work. Although the unusual scrambling techniques of the early sections make them exceedingly obtuse, the patient reader will eventually find his reward in the clarity and simplicity of the final chapter, 'Money Made from Stolen Fruit,' with its extraordinary sentimental eulogies to his early mentors La Volpe and Il Gatto, from whom he admits most of his ideas were taken. 'They made me what I am today,' the great scholar confesses, providing fresh and startling new insights into the true sources of his peculiar, though now perhaps questionable, genius "

"Mascherine!" the professor hisses between clenched jaws. He feels he is about to explode. Even this they have stolen! His work! His reputation! His very life! "Assassini!"

"Are you all right, master?" asks Truffaldino softly, leaning close. "You don't look so well !"

The priest and nun are long since gone, of course. As is, once more he notes, his watch. "Take me home," he whispers hoarsely, his whole body trembling. It is all over. Like his beloved San Petrarca before him, he is tired in body and soul, tired of everything, tired of affairs, tired of himself "I have lived long enough. I am ready to die."

But then, just when ("Why not," he can hear Truffaldino saying with a shrug, "we're going that way anyway ") all hope vanishes, something occurs that reminds him forcibly of his old babbo's favorite saying. "One never knows, carogna mia," he would say, tipping his dirty yellow wig slyly down over one eye and sucking wickedly at his grappa jug, "what might happen next in this curious world "

24. LA BELLA BAMBINA

It is to be believed, as Father Tertullian once said, leaping from paganism to the Apocalypse in a single bound, because it is absurd. It is certain because it is impossible: Tonight he is to have her at last! In his case, too, the miracle has owed something to the Apocalypse, though he can hardly be said to have leapt, and the Apocalypse in his tale of redemptive grace was a Carnival ride on the Riva degli Schiavoni: no mere mystical vision, that is, but an extraordinary and dizzying reality. Even now, he seems to lose his balance whenever he thinks of it, an experience he has never felt when contemplating something relatively so frivolous as the end of the world — and that magical ride was as nothing compared to what is yet to come before this day is over! "At last, tomorrow," Eugenio promised him yesterday, after making the arrangements, "your biggest wish will come true!" His mind cannot even quite take it in, though the rest of him is certainly more than ready, his whole body trembling in anticipation of that which, for his staggered imagination, remains ultimately unimaginable. As Bluebell put it on the Apocalypse yesterday, begging him to hug her close: "Wow! I'm so excited, teach, I feel like I'm about to wet my doggone pants!"

"Easy, master! You'll tip us over!"

"We'll be there soon enough!"

Yes, they are rocking dangerously, standing huddled there together in the frail gondola in the middle of the Grand Canal, both shores now lost to view in the damp cold fog of this wintry Mardi Gras morning, lost to his view anyway, but it doesn't frighten him, nothing frightens him since his wild ride on the Apocalypse, he feels reckless and manly and heroic, invulnerable even, and he responds to their silly fears with devil-may-care laughter, which unfortunately comes out more like deranged cackling, no doubt making him sound to the servants porting him completely fazzo, as they'd say — as indeed, in love, he is. Stark staring.

"Brr! What a cold stinking soup this is!"

"It's like the old Queen let one and it froze!"

"If this caeca gets any thicker we'll have to shovel our way across!"

For the professor, the dense fog which rolled in last night is full not of threat but of tender promise, an obliging curtain dropping upon the past, dissolving its regrettable angularities, so harsh and obstinate, in the sensuous dreamlike potential of the present. It is as though the city were masking itself in buoyant anticipation of secret revels of its own, hiding its shabbiness and decay behind a seductively mysterious disguise which is not so much a deception as an amorous courtesy. "The important thing about Carnival," he wrote recently in a note intended as part of his monograph-then-in-progress, "is not the masking, but the unmasking, the revelation, the repentance, the re-establishment of sanity," but, as always in all the days before yesterday, he was wrong. The important thing is the masking. What is sanity itself, after all, but terror's sweet foggy disguise? And love the mask that shields us from the abyss, art its compassionate accomplice?

These poignant thoughts come to him unbidden, full-formed already in a language, though chaste, clearly steeped in Eros's ennobling power (only now could he write that monograph which now he knows he will never write), swirling through his quickened mind as easily as do the coiling twists of fog here upon the still gray surface of the Grand Canal. This fog has caused the suspension this morning of all motorized water traffic and so forced upon them this slow labyrinthine journey to the mask shop by foot and now traghetto, a journey whose purpose is, in effect, to initiate a healing, providing him the means, designed by Eugenio, by which to rejoin, after the misguided century, his life's lost theater. He will put a new face on and, in love's name, learn to lie again, free at last from the tyranny of his blue-haired preceptress with her "civilizing" mania, her cruel tombstone lessons. The long oar splashes softly behind him as the black-snouted bark carves its perilous way across the silent waters, drawing a line erased as soon as drawn, thus celebrating, not the line, dull as death itself, but the motion that has made it. The others stand in a cluster in the rocking gondola like passengers on a crowded bus, holding him up between them, chattering nervously and peering intently through the purling mists for a glimpse of a landing, as though afraid that what they cannot see might not exist. Though impatience grips the old scholar, fear does not, and, least of all, the fear of movement, once such a bugbear that even melody's traveling line offended him and his gardens all were paved so as not to have to witness growth. No more. Movement, after all, was his very raison d'ętre, he was made for it. "To dance and fence and turn somersaults in the air," as his father advertised. His concept of I-ness, as he tried to explain yesterday to his former student, aboard the whirling Apocalypse, was never more valid: he could not, without doing violence to himself, be other than what, at the core, he was. "And only here, dear Bluebell, right now, where I am, am I truly what I truly am!"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.