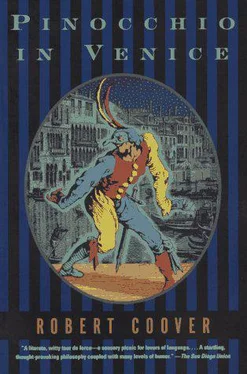

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This power of flesh to go its own way became the subject (perhaps he had been talking aloud again, quite likely) of several of the Madonna's ceremonial performances as they went along the route of late lamented pissoirs. She would light the seminally blessed votive candles with her apple green heart, which worked like a kind of miniature blowtorch, empty her bladder on the site of the displaced pisciatoio, and with her spleen lead a communal prayer for making public urinals and ridotti out of all the city's banks and churches: "Piů cessi meno chiese!" they would chant. Then, after Count Ziani-Ziani had recited from what he called the Ancient and Holy Testament of Latrine Grafitti, she — or, more precisely, her organs — would sermonize briefly on various topics such as individual organ and glandular rights, cruelty by civic neglect of the tragicomically fused genito-urinary twins, or the body politics of visceral autonomy versus a united organic front, the various glands and organs sometimes getting into heated debates and even duels with one another, all trying to shout at once, the liver blackening with rage, the stomach turning sour, the bowels complaining rudely, the heart winning most arguments finally with its lethal blowtorch, the Madonna's body becoming a kind of strange traveling puppet booth, the organs her fractious tattermen. Finally, the larynx or the adenoids or the vagina would bring all the spitting and screaming and squirting of this anatomical psychomachia to an end by singing the Benedictus, the anus at the end of its long undulatory tube providing the resonant antiphon, and then the Madonna would deliver a few dozen marzipan Jesuses from her womb and pass them out to the children

Here in this campo, after the opening rituals, she and her organs, having paused to reflect upon martyrdom, had taken up as a case in point the professor's nose, on rubber-masked display above his "ECCE NASUS" sign, debating the question: which was the true martyr, his nose or the rest of him? Not surprisingly, the more exposed parts opted for the abused and repressed ("Hamstrung," was the way the hamstrings put it) nose, the glands and internal organs arguing contrarily on behalf of the inner humiliation and suffering brought to the whole by the offending part, which the fulminating colon called an intolerable pain in the butt and the uterus said wasn't worth a dried fig and, for its sins, as much of omission as commission, probably ought to get the chop. "I've had it up to my hair with the stuck-up thing!"

"That's right," agreed the adrenal glands, "let the snotty nuisance stew in its own juices!"

"I see what you mean," observed the eyeballs on their little strings. "At first glance, the little blowhard does appear to be something of a fist in the eye and more than a bit uppity, but it is our view that only the branch can be said to be martyred when the tree, for its own good, is pruned!"

"Right, I can swallow that," piped up the esophagus, and the shrunken kidneys, siding with the eyeballs, added: "Moreover, if the fault is in the handle, as the saying goes, so then is the anima: dismemberment hallows the honker!"

"I speak," said the heart, flaring up briefly, "from the heart when I say that your argument, my dear kidneys, doesn't hold water. The holy martyrs were canonized for their good hearts, not good hooters!"

Thus, inevitably, the debate, which grew increasingly tempestuous ("You're getting up my nose, you cardiocentric four-flusher!" screamed the sinuses, and the ovaries started throwing eggs again), evolved into a raucous theological dispute about the true location of the soul, each organ staking its claim as sole container of the elusive stuff, the lungs bellowing that insufflation had been the true sign of life since God first puffed up Adam, the brain retorting heatedly that the soul was inseparable from the logos and that to think otherwise was unimaginable idiocy, the mammary glands doing a bit of breast-beating of their own, and the rectum airing its "gut feeling" that, since everything else in the world got stuffed up it, the soul must, willy-nilly, be there as well. "Macchč! I haven't the stomach for this," rumbled the stomach acidly, burned by the heart and vainly seeking relief from the spreading crossfire, which came finally from on high with the head-over-heels arrival of the Winged Lion, explosively interrupting the performance.

Throughout all this, the professor had been watched at some distance by the mournful old priest he had noticed back at the foot of the Accademia bridge, standing now across the little campo, together with his companion, the blind nun, under a circus poster for tomorrow night's Gran Gala. Perhaps they were waiting for him to resolve the dispute of the organs with one of his famous Augustinian disquisitions on the "changeless light within," an image he had once found useful in trying to recapture the peculiar essence of his prenatal (so to speak) life on the woodpile. No, I am sorry, my friends. No resolutions. The light's gone out. He has never been afraid of course to speak of the "soul" or "spirit" ("I-ness" was in effect a word for this), though he has often wondered why men born to real mothers did, and indeed it could be said that his entire Mamma project had been really little more than a homiletic account of his idiosyncratic search for the magic formula by which to elevate his soul from vegetative to human form, as though body, far from being a corrupting adversary, were in itself a kind of ultimate fulfillment. Soul itself, in the particular.

Now, left alone by the Lion's crash landing to savor, hunched over his scabs (has he found at last, he wonders, picking at them, his closing image?), the manifest ironies of his life's quest, he is approached deferentially by the limping priest and his ancient companion, stumbling along on a cane. "Scusi, signor professore!" rumbles the holy father softly in his gravelly old voice, bowing slightly and tipping his black hat, and the nun, nodding circumspectly, whispers as though in awe: "Professore!" "We are profusely honored, il nostro caro Dottore Pignole," the old cleric continues with another little bow, "to have your sublimated presence among us! We hold your nugaciously pleonastic writings here in grand esteem, alla prima, and consider them to be, as the saying goes, of the most beautiful water!"

"Yes," whispers the nun, her old head bobbing, "your water is very beautiful!"

"They have, as we Veneti say," the priest is quick to add, " la zampata del leone, the paw of the lion, that is to say, the indisputable footprint of genius and caducity. We few, to whom such things still have provenance, from the bottoms of our unworthy souls, if indeed they have bottoms, exalted sir, and who would know better than you, thank you!"

"You are welcome," replies the antiquated nun, then wheezes deeply as though suffering a sudden pain in her lower ribs.

"I–I am not who or what you think I am, father," the old professor confesses abjectly.

"You are not Professor Pinenut — ?" asks the priest, peering closer. The nun, in seeming confusion, turns to hobble away, but the priest snatches her by her habit and draws her back.

"Yes — no, I only meant — "

"Ah. You speak metaphorically, of course, true to your majestic and incogitant stylus. We are all, souls masked by bodies, other than what we seem to be, and yet what we seem to be, in the soulless barter of the bodied world, we also are, and so, though not Professor Pinenut, you are he nonetheless! I trust then you will not deny us a trifling favor, good sir: to wit — "

"Good, sir," says the nun. "Do it."

"- To wit, to sign one of your noble and predacious tomes for our parish library, hoping that is not too magnanimous an imposture for such a gran signore — ?"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.