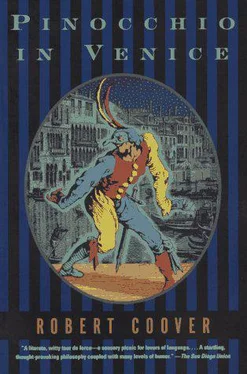

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

On either side of the doorway through which he had been ported in such haste, posted there in their voluptuous robes like candidates for honorary degrees or guests at a royal feast (Veronese again, to be sure, that sybaritic host) and coldly examining him now in his doddering ignominy, stood the warring figures from his own and Petrarch's intellectual history, Aristotle and Plato. Plato's gaze, though full of disappointment and sorrow, was essentially benign, like that of a forgiving lover, but Aristotle, dressed as a Moorish prince, appeared to be glaring fiercely at him, giving him the big eye, as they say here, as though enraged at the bad press the professor had given him all these years. He had made Aristotle — and standing there on his trembling pins, feeling the chill of hostility in the air, needing all the friends he could find, he nevertheless did not regret this, and so, bravely, with what eye remained, returned the glare — the emblematic target of his lifelong dispute with those who substituted mere problem solving and art-for-art's-sake banalities for the pursuit of idealized beauty, and thus of truth and goodness as well. Aristotle and his vast camp following had unlinked art from its true transcendent mission, reducing it to just another isolated discipline, one among many, the worst of heresies, he deserved no quarter even had he any, in his extremity, to give.

Perhaps a cloud went by, or else it was a trick of his old eyes, but Aristotle seemed to wince as though at a bad odor and turn away, dismissing him with a contemptuous shrug, while Plato's austere expression, contrarily, appeared to soften, a faint appreciative smile curling the great sage's lips. His aged disciple, confused but moved (though move in fact he could not), dipped his nose in modest homage to the master, whereupon Plato, his rosy robes rustling gently, lifted one hand, puckered his fat lips, and, with a coy wink, blew him a kiss. The professor started, Plato's eyes rolled up to stare in alarm at the ceiling, he jerked his own head back and — crack! pop! — there it stuck, his rot-decayed neck locked, his nose pointing up at Il Padovanino's barbarous allegorical roundel, while around him the venerable philosophers wheezed and giggled like mischievous schoolboys. Which is when Bluebell came in and said: "Hey, Professor Pinenut! What a surprise! Whatcha lookin' at?"

There was a time once, he was still a young man in his early sixties, when he decided that writing about the decline of art in the Western world was not enough, he had to become a painter himself and establish the new classical norms by example. Futurism, expressionism, cubism, surrealism, abstraction, op art and pop art and all the rest: just forms of iconicized naughtiness, when you got down to it, and he felt it was up to him to recover art's ancient integrity, its sense of duty, its inherent grandeur. No more self-mocking irony, no more moral shilly-shallying, but true devotion: this was his cause, so he bought himself a box of paints and pencils and turned up at life-drawing class. It was not something he could accomplish overnight, he knew that, his eyes were open, but no one understood the history of art better than he did and he had been pretty good at basket making, so he figured it was just a matter of time, a year or two perhaps, he could be patient. He took to wearing berets, smocks, and neckerchiefs, and let the four or five hairs on his upper lip grow.

As it happened, the model for the art class was a student in his Art Principles 101 (was it this student? he couldn't be sure, but he thought not, remembering the girl as shy and delicate with body hair the color of burnt sienna dulled with a touch of Sicilian umber, which he had to go out and buy separately since it wasn't in his paint box), and about three weeks into the semester she came to see him late one afternoon during office hours. This was before the time of tights and miniskirts, it was more a ponytail-and-bobbysocks time when skirts were full and long and often pleated, and so, as she came in and sat down in his office, her flexing hips and legs were more like the subtle implications of hips and legs enveloped as they were in the soft contours of her flowing skirt, and, he thought as she gathered the folds around her, expressing a thigh here, hiding a knee there, much more provocative than when seen in the flesh, which he tended to look on primarily as a technical problem. That choice of roughly five parts of burnt sienna to one of Sicilian umber to capture the soft dark luster of her body hair, for example, was dictated in part by reality and his close examination of it, and thus captured something of the absolute for which he was always searching, but it was also tempered by the inconstant flesh tones of her circumambient thighs and abdomen, which seemed sometimes pale, almost bluish, and at other times tenderly flushed, almost aglow, and so threatened him with that relativity he so abhorred: if not even private hair color was constant, what then was Truth? An important question, perhaps none more so, yet one that seemed strangely irrelevant in his office that afternoon as he caught a teasing but imprecise glimpse of pale shadowy thigh when she crossed her legs and said: "That's just it, Professor Pinenut: it's — it's your nose!"

"What — ?" He realized then it had been growing and had become engorged and feverish at the tip, and, as always on such occasions, he ducked his head and buried the unruly thing in a handkerchief. "Sorry, Miss, just a bit of a — !"

"I always get the feeling, you know, in the studio, that you're painting with your nose, and it gives me a very eery feeling, not so much in the art class itself where it seems almost natural, even when it bumps the canvas and gets paint on the end of it or when it's down between my knees when you're mixing colors, but in your lecture class when you're all dressed up in your nice wool suits and standing up there on the platform in front of everybody like the president or something and pointing it straight at some art slide you're showing, and, well, it's suddenly so — so naked!" She blushed and pushed her trembling hands between her knees, tightening the skirt around her hips. "It — it almost scares me, and I get this funny feeling between my legs like, well, like God's there, you know, doing something, and I can't even hear what you're saying anymore and everything else just disappears and all I can see is your nose and I can hardly breathe and I'm wet and trembling all over and probably the other kids around me are laughing but I don't even know they're there, there's just nothing in the world except your nose, pointing at me suddenly, like it is now, and this weird overwhelming feeling, even now I can almost — oh! — almost not stop it! — and what I'm wondering, Professor Pinenut, what's — gasp! — got me scared is, well — ah! — am I the Madonna?"

That was when he shaved his upper lip and gave up painting. And that was when he stopped blaming individual painters for the tragic decline of art. He now knew they couldn't help it. It was just how things were.

Which is more or less what he is thinking now when Bluebell, who is still cuddled up close with her arm around him, whispers in his earhole: "You know, Professor Pinenut, sometimes I think I don't even like paintings, even great ones like that one up there on the ceiling. They just seem so dead or phony or something, like those photos they put up outside movie theaters to advertise the films they're showing and which aren't anything like the films at all. But just watching you look at a painting like you are now — I don't know, maybe it's your nose or something, how intense it gets, how excited, like it's really on to something — whatever, I just get this tremendous feeling that, even though I'll never understand it, something great is happening, and it's enough for someone like me just to be close enough to pick up the vibrations. If I'm too dumb or insensitive to feel what you feel, you know, at least I can feel you feeling it!"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.