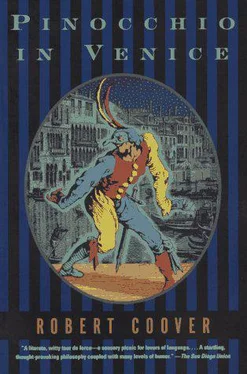

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Ah, poor Pini! And still a virgin, then!"

"Well, not quite " He lowers his head, his nose inscribing its usual ignominious arc through the liquid night air, and stares out at the lagoon, pitch black except for the glittering gold coins cast on its surface by the yellow lamps of the channel markers and illusorily deep as an ocean. He lets his gaze drift out upon it, losing focus in its seeming immensity, floating deep, deep into the void, acknowledging his lifelong yearning to hide himself from life's profuse terrors and confusions upon the bosom of the simple, the vast, and surrendering for a moment to his ancient appetite, as perverse as the day Geppetto chopped out his rough-hewn little torso, for the absolute anarchy of the eternal emptiness, that incommunicable but ineradicable truth of his pagan heart, which the Blue-Haired Fairy so abhorred. In effect, civilizing him, she taught him, if not his intractable nose, how to lie "There was the night I I became a boy "

"Aha !"

He'd been wearing himself out, doing the sort of donkey work he'd been spared in his donkey days, harnessed to the primitive water-wheel that had killed his old friend Lampwick, just to earn a glass of milk each day for his grappa-crazed babbo, now on his last legs. The times were hard. Since their escape from the monster fish, they'd been holing out in an abandoned straw cottage that was insect-ridden and stank of goats, sleeping on beds of rank straw, dressed in rags and half starving. The farmer he worked for was a tyrant, but no worse than his old man, who hated him still for dragging him out of Attila's innards, the best home he'd ever had. At the time, he'd felt that he was saving him, but now he didn't know for what. The old loony, now calling himself San 'Petto, raved all day and often as not all night, spat out the milk he brought him from his backbreaking labor, peed spitefully on their straw mattresses, left his other evacuations around the cottage wherever he felt like. Saint's relics, the old boy called them. So as to have something to trade at the market, he'd taken up basket weaving and, whenever he was away at market or off pushing at that murderous waterwheel, his father would throw his handiwork down the well or set it on fire or chop it up and try to make grappa out of it. He'd knocked together a little cart to use on his trips to the market, and Geppetto had torn up three of his best baskets, braided a whip out of the raffia, and bullied him into pushing him around in the thing. That was all right, at least it kept him quiet, if only while he was in it, and the whip didn't hurt, the old brute was too far gone to do more than wave it about like a blind man's cane. It was the meanness of it that hurt. The Disney film had captured something of Geppetto's stupidity maybe, but not his malice. On one of his trips to market, he had picked up an old coverless primer with half its pages missing, the very one perhaps he had sold for a ticket to Mangiafoco's puppet theater, and had begun to teach himself to read and write, and in this book, under "M for Madonna," was a picture that, though he did not know it at the time, was eventually to change his life: a reproduction of Giovanni Bellini's "Madonna of the Small Trees." He could not keep his eyes off it, returning to it time and again. Maybe he identified with the stunted trees. Whatever, it utterly absorbed him. "M" was the letter he learned best in the alphabet, and it was still his favorite. It was no accident that the title of his final opus, only five letters long, was to have had three of them in it. This primer was the treasure of his life and his sole consolation. Until Geppetto mustachioed the Madonna of the Small Trees and drew a penis in her mouth, then drank up all his fruit-juice ink and smoked the shredded pages, "M" the first to go.

"Poverino!"

"It was awful. I couldn't help but feel sorry for myself. I cried all the time. The Fairy was out of my life forever, I was stuck with this mad old man, I'd watched my best friend die a miserable death that seemed to foretell my own, I was working fourteen-hour days and getting nowhere and I felt like all my joints were coming apart from the physical strain, I was cold and hungry most of the time, and I was utterly alone. My old enemies the Fox and the Cat were somewhere in the neighborhood, down on their luck, Il Gattino who'd once feigned blindness as a beggar now blind in fact, La Volpe crippled and her tail gone, both of them desperately needy but also probably dangerous. I'd chased them off but knew they might return at any moment to steal what little we had, the scraps of food, the baskets, the few coins I'd managed to put aside from my market dealings. So one day, deciding I'd better spend those coins while I still had them, I took them to market to buy myself some new clothes. As I walked down the road, I imagined myself making a fresh start. You know me, always the irrational optimist, fields of miracles, money trees, zin, zin, zin, and all that. Why not, I thought. I knew at least half the letters in the alphabet by then and figured I could fake the rest and so perhaps move up into the professional classes. But "

"Ah yes. With you, dear friend, there's always a but "

"On the way I met La Lumaca, the Blue-Haired Fairy's sluggish maid, the one who once took twelve hours to bring me plaster of Paris bread and alabaster apricots when I was sick from hunger."

"Ha ha! And she told you the Fairy was dying, no doubt, and was temporarily short of funds !"

"That's right. She said she didn't even have enough to buy a crust of bread. I gave her all I had."

"Ah, poor Old Sticks!"

"It was nothing to me. I was overwhelmed by hope and despair at the same time. I ran back home and started making more baskets. I doubled my production in a single evening even though I was crying so hard I could hardly see, the tears streaming down my nose like a rainspout. I was going to save her life with baskets. I'd work till dawn, and then till dawn again, and for as many dawns as it would take. But I was too exhausted. About midnight I fell asleep. And I had a strange dream "

He was back in the Fairy's little snow white house in the dark forest. He didn't remember how he got there, but there was something before about pushing his sodden father, or perhaps the carcass of his dead friend Lampwick, in the little wooden cart he had made. Whoever it was was very heavy and the going was slow. Far far ahead in the dark night he could see the old Snail, lit up like a porcelain-shaded nightlamp, and crying: "Hurry! Hurry! You'll be late!" But pushing against the cart was like pushing the terrible waterwheel. La Lumaca disappeared and the night came down on him like a coal sack. But then, without transition, it was he who was being carted, just like the first time, into the Fairy's cottage. She was little like she was when he first met her with her waxy face and spooky eyes and strange blue hair, and they were playing doctors again, or something like it, though this time he was completely dead. She laid him on her bed and took all his clothes off. Then she removed his feet, took his knees apart, unhooked his legs where they were pegged into his body, popped his faucet out like pulling a cork. She did the same thing with his arms and head and all the rest, took him apart joint by joint. Though it should have been scary, it was in fact very relaxing. When she unplugged his nose he felt like he could really breathe for the first time in his life, even though he was dead. She put all the parts together in a pile and played with them for a while like wooden blocks, making little houses with them and knocking them down. It didn't hurt and he felt freed from responsibility, though it made him dizzy when she rolled his head around. When any of the pieces got dirty, she licked them and rubbed them clean on her dress, which was more like a winding sheet. They seemed to need a lot of cleaning, so she took off her clothes and rubbed them all over her body, which was smooth and slippery like a bar of soap, kissing them and licking them and caressing them at the same time. It felt wonderful, especially when she pushed the pieces down between her legs, where her softest parts were. She was on her back now, fondling and stroking all his segments, and though he couldn't see very well anymore, he could feel how each part of him got pushed up into the warm wet place between her thighs and scrubbed around in there and then came out again, hot and soaking, his torso too, though he didn't know how she managed it, little flat-tummied thing that she was. When his head went in, he caught just a glimpse of the crimson slash amid the waxy pallor like rose petals buried in ice cream, and he was afraid she might have hurt herself, she was moaning and yowling now and pitching about as though in horrible pain, but she slapped him playfully and growled at him to "Close your eyes, you little scoundrel!" in a voice that didn't sound like a little girl at all, and pushed him on in where everything was soft and creamy and utterly delicious, he didn't want to come out again, he just wanted to push deeper and deeper and stay there forever. But while he was in there — his head at least, he could still feel the rest of him in a wet scatter outside — he seemed to hear her speaking to him: "Bravo Pinocchio!" she said. "Because of your good heart and other parts I forgive you everything!"

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.