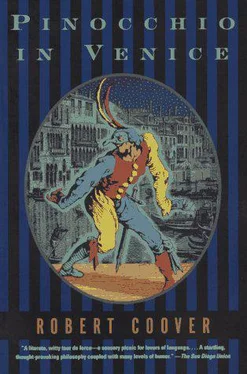

Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Pinocchio in Venice» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1997, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pinocchio in Venice

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1997

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pinocchio in Venice: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pinocchio in Venice»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pinocchio in Venice — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pinocchio in Venice», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"Io rimango," he thought to himself, recalling his futile resistance, as futile now as it was then: here still, but not for long. He was not getting well. He was feeling less pain, no doubt thanks to Eugenio's pharmaceuticals, and he was able, if carried, to get about a bit, but if anything his disease was worsening. The bits that had fallen off were gone for good, awash somewhere in the waterways of Venice, and more vanished every day, teeth and toes in particular, and the patches of flesh that kept flaking away, fouling his sheets with dusty excrescences sometimes as large as dried mushrooms. And what was left of him, once waterlogged, was twisting and splitting now as it dried out, he could hardly move without startling those about him, himself included (this is not me, he continued to feel deep in his heart, or whatever was down there, there in that dark place inside where all the weeping started, this can't be me!), with awesome splintering and cracking sounds, his elegant new clothing worn not merely to conceal the surface rot, but to muffle the terrible din of the disintegration within. He would shed the rest of his flesh altogether and be done with it, but it sticks tenaciously and bloodily to his frame like a kind of stubborn reprimand, his attempts to scrape it off causing him excruciating pain. Far from transcending flesh, he was dying into it. Into the tatters of it. Only, as he shrank toward oblivion, his love for her and a certain bitter dignity remained

"I loathe small deaths," Eugenio was saying. "Death is our great master, but must be met with the grandeur it deserves!" The old professor, emerging from his revery, realized that Eugenio had been describing for him the magnificence of the Little Man's final rites, beginning with a great requiem Mass in the colossal church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in the company of twenty-five dead doges and the skin of Marcantonio Bragadin, who was flayed alive by the Turks at Famagusta (perhaps Eugenio had told him this in response to his own complaints, or else, speaking his thoughts aloud, he had complained of his own slower flaying upon hearing of that of the hero of Famagusta, whose skin at least was whole enough to be saved as a relic and not shaken out each day with the changing of the beds), followed by a solemn funeral procession around to the Fondamenta Nuova with all the bells of Venice tolling (as, from over the lagoon, they were hollowly, as though in wistful remembrance, tolling at that moment), the hearse drawn by sixty-nine leather-booted donkeys who were later driven into the sea and drowned. There, the Little Man's coffin was removed to a gold and black funeral gondola, heaped with orchids and roses and palm branches, and, followed by other gondolas carrying the statues of the angels now mounted on the tomb and all the thousands of L'Omino's admirers and lovers, brought across the Laguna Morta to this island, the church here draped that day in black and silver and bearing, freshly engraved on the cloister gateway under Saint Michael and the dragon, where it could be seen still, another of L'Omino's immortal lines: "While the world sleeps, I sleep never."

"I–I never realized," the old scholar stammered, filling the momentary silence, "he was so-so-so "

"Loved? Oh yes, but it's not what I brought you here to show you," Eugenio replied with a sly vulnerable smile. "Lift him over here," he instructed the servants and, crossing himself as he passed the tomb and genuflecting gently, he led them to the naked angel, stage right, poised balletically on one foot as though in imitation of the beautiful angel in blue on the Pala d'Oro. "Look, Pini. Do you recognize him?"

Not exactly an angel after all, he noted, for it had a little inch-long uncircumcised penis and two tiny testicles like polished glass marbles which Eugenio now fingered affectionately. "I–I'm not sure The, uh, face "

"Yes, you have guessed it," Eugenio groaned, leaning his head almost shyly against the angel's pale thigh. "It is I, as I was, when L'Omino first loved me." He ran his finger in little loops through the artfully scrolled pubic hair, traced the contours of the childish abdomen, poked the tip of his finger into the deep navel. Yes, that's right, the creature also had a navel. "Now now it sticks out like like a little clitoris," Eugenio confessed, touching his own round tummy. He tried lamely to laugh through the tears that were now streaming down his cheeks. It's true, the professor thought, squinting up at the marble face with its pursed bow-shaped lips, its long-lashed eyes and flowing locks, it did quite resemble the Eugenio he once had known, and in particular — perhaps in part it was the ghastly pallor of the stone, or maybe the halo, tipped back like a cockily worn school cap, the wings attached to the shoulders like bulky bookbags — that Eugenio who lay sprawled on the beach that dreadful day, seemingly dead or dying after being struck down by the math book; but at the same time this was a different Eugenio, a more mature one to be sure, a more intense and self-assured one than the boy he had known, but also (he was gazing up at the eyes now, eyes not unlike those he had seen in certain paintings as the light of the Renaissance dimmed) one clearly in touch with the nuances and deceptions of power and exchange, one who had already come to know pleasures and the pitfalls of pleasure and who had ceased to search for something that could not be found, one privy — like an angel, one might say — to the world's bleakest secrets and embracing them

The living Eugenio, the short butterball one with the fat crinkly face and slicked-back hair, was running one thick bejeweled hand up a taut thigh, hugging it to him, while caressing the marble buttocks, their luster attesting to the frequency of such devotions, with the other. "Ah, che culo!" he exclaimed throatily, covering it suddenly with passionate kisses and wetting it with his freely flowing tears. "How I wish now, Pini," he blubbered, "I could fuck myself as I — choke — was then!" He bawled there for a moment, cheek to cheek, his arms around the statue's hips, and then, when he could, he gasped: "You see, dear friend, that sweet bottom won L'Omino's heart, and — sob! — changed my life forever! It made me, fundamentally, in a word, what I am today! Che culo, we say: what luck, eh! And it gave good value. He beat it, bit it, slapped and tickled it, slept on it, sat on it, used it as a canvas, a pincushion, a footstool, a musical instrument, ate his supper off it, whispered his most intimate secrets to it and, as you might say, wrote his will on it. By the time its glory had begun to sag, L'Omino was dead and it was I who was choosing favorites "

Then Eugenio wiped his eyes and blew his nose and, still embracing the statue affectionately, told the professor about his own life at the Land of Toys, which was not at all like the one he and Lampwick had known, nor could they even have imagined it. "It all began," Eugenio sighed, "that first night when the Little Man lifted me up onto his lap and let me hold the reins as we bounced down the road to Toyland. The other boys all envied me, but in truth, I soon felt shackled by those unfamilar straps tugging insistently at my hands. Such a strange dark journey, Pini, the little donkeys clopping along in front of us in their white leather boots, the only things you could see by that night's eery light, and making odd snuffling and whimpering noises, while the Little Man shushed them with ominous lullabies sung through clenched teeth and cracked them with the whip which whished terrifyingly past my ear from time to time. I tried not to cry, but I couldn't help it. I was trembling all over like a leaf in a temporale. The Little Man, in his fashion, consoled me. By dawn, I was no longer a virgin " Eugenio sighed tremulously and stroked the statue's buttocks tenderly as one might to soothe a tearful child, then went on to tell him how, when they arrived and all the other boys ran off to play, he was carried under L'Omino's arm like a pig from market, arse forward, school knickers still in a twist around his ankles and blood trickling down his thighs, to the Little Man's private rooms, then in a modest corner at Venice's eastern tip near where the soccer field now stands, itself a commemorative gift to the city from Omino e figli, S.R.L. Here, L'Omino kept a little stable of his favorites whom he treated like donkeys but left, at least most of the time, in the shape of boys, the games they played being the sort one might associate with a stable. "Well, tutti i gusti sono gusti, as the Little Man himself used to say, his own being mostly of the Tyrolean sort "

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pinocchio in Venice» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pinocchio in Venice» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.